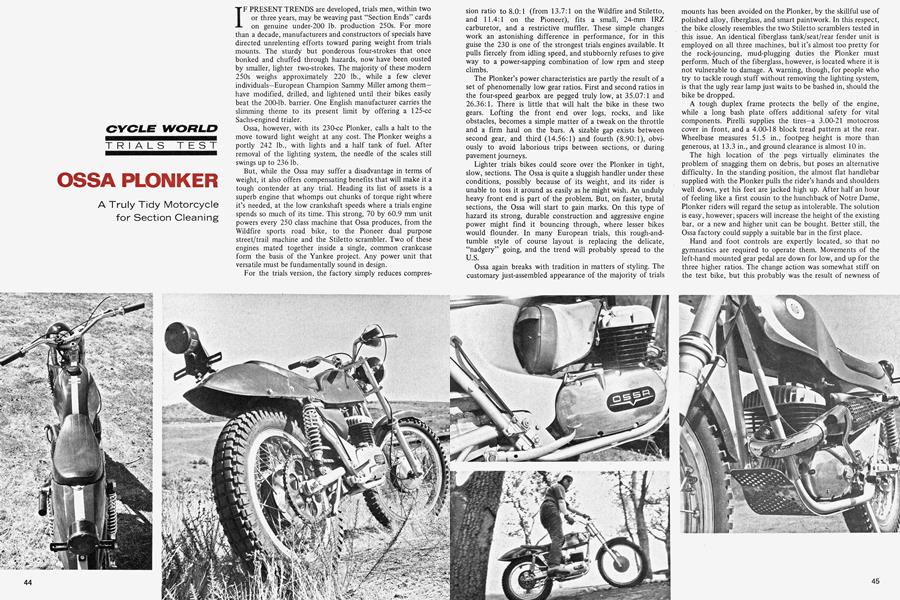

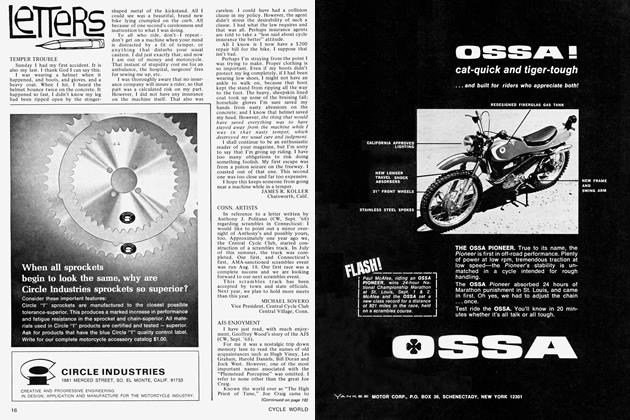

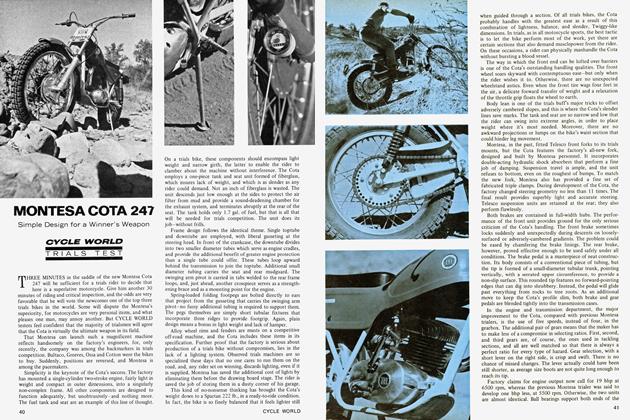

OSSA PLONKER

CYCLE WORLD TRIALS TEST

A Truly Tidy Motorcycle for Section Cleaning

IF PRESENT TRENDS are developed, trials men, within two or three years, may be weaving past “Section Ends” cards on genuine under-200 lb. production 250s. For more than a decade, manufacturers and constructors of specials have directed unrelenting efforts toward paring weight from trials mounts. The sturdy but ponderous four-strokes that once bonked and chuffed through hazards, now have been ousted by smaller, lighter two-strokes. The majority of these modern 250s weighs approximately 220 lb., while a few clever individuals—European Champion Sammy Miller among them— have modified, drilled, and lightened until their bikes easily beat the 200-lb. barrier. One English manufacturer carries the slimming theme to its present limit by offering a 125-cc Sachs-engined trialer.

Ossa, however, with its 230-cc Plonker, calls a halt to the move toward light weight at any cost. The Plonker weighs a portly 242 lb., with lights and a half tank of fuel. After removal of the lighting system, the needle of the scales still swings up to 236 lb.

But, while the Ossa may suffer a disadvantage in terms of weight, it also offers compensating benefits that will make it a tough contender at any trial. Heading its list of assets is a superb engine that whomps out chunks of torque right where it’s needed, at the low crankshaft speeds where a trials engine spends so much of its time. This strong, 70 by 60.9 mm unit powers every 250 class machine that Ossa produces, from the Wildfire sports road bike, to the Pioneer dual purpose street/trail machine and the Stiletto scrambler. Two of these engines mated together inside a single, common crankcase form the basis of the Yankee project. Any power unit that versatile must be fundamentally sound in design.

For the trials version, the factory simply reduces compression ratio to 8.0:1 (from 13.7:1 on the Wildfire and Stiletto, and 11.4:1 on the Pioneer), fits a small, 24-mm IRZ carburetor, and a restrictive muffler. These simple changes work an astonishing difference in performance, for in this guise the 230 is one of the strongest trials engines available. It pulls fiercely from idling speed, and stubbornly refuses to give way to a power-sapping combination of low rpm and steep climbs.

The Plonker’s power characteristics are partly the result of a set of phenomenally low gear ratios. First and second ratios in the four-speed gearbox are pegged truly low, at 35.07:1 and 26.36:1. There is little that will halt the bike in these two gears. Lofting the front end over logs, rocks, and like obstacles, becomes a simple matter of a tweak on the throttle and a firm haul on the bars. A sizable gap exists between second gear, and third (14.56:1) and fourth (8.90:1), obviously to avoid laborious trips between sections, or during pavement journeys.

Lighter trials bikes could score over the Plonker in tight, slow, sections. The Ossa is quite a sluggish handler under these conditions, possibly because of its weight, and its rider is unable to toss it around as easily as he might wish. An unduly heavy front end is part of the problem. But, on faster, brutal sections, the Ossa will start to gain marks. On this type of hazard its strong, durable construction and aggressive engine power might find it bouncing through, where lesser bikes would flounder. In many European trials, this rough-andtumble style of course layout is replacing the delicate, “nadgery” going, and the trend will probably spread to the U.S.

Ossa again breaks with tradition in matters of styling. The customary just-assembled appearance of the majority of trials mounts has been avoided on the Plonker, by the skillful use of polished alloy, fiberglass, and smart paintwork. In this respect, the bike closely resembles the two Stiletto scramblers tested in this issue. An identical fiberglass tank/seat/rear fender unit is employed on all three machines, but it’s almost too pretty for the rock-jouncing, mud-plugging duties the Plonker must perform. Much of the fiberglass, however, is located where it is not vulnerable to damage. A warning, though, for people who try to tackle rough stuff without removing the lighting system, is that the ugly rear lamp just waits to be bashed in, should the bike be dropped.

A tough duplex frame protects the belly of the engine, while a long bash plate offers additional safety for vital components. Pirelli supplies the tires—a 3.00-21 motocross cover in front, and a 4.00-18 block tread pattern at the rear. Wheelbase measures 51.5 in., footpeg height is more than generous, at 13.3 in., and ground clearance is almost 10 in.

The high location of the pegs virtually eliminates the problem of snagging them on debris, but poses an alternative difficulty. In the standing position, the almost flat handlebar supplied with the Plonker pulls the rider’s hands and shoulders well down, yet his feet are jacked high up. After half an hour of feeling like a first cousin to the hunchback of Notre Dame, Plonker riders will regard the setup as intolerable. The solution is easy, however; spacers will increase the height of the existing bar, or a new and higher unit can be bought. Better still, the Ossa factory could supply a suitable bar in the first place.

Hand and foot controls are expertly located, so that no gymnastics are required to operate them. Movements of the left-hand mounted gear pedal are down for low, and up for the three higher ratios. The change action was somewhat stiff on the test bike, but this probably was the result of newness of the machine. The front brake is carried inside a hub that is huge by trials requirements. Here is a probable source of some of the bike’s front-heaviness. To be fair, though, several other production trials mounts are burdened with equally large hubs.

A previous test of the Ossa (CW, March ’68) complained of insensitive operation of the rear brake. This time, it functioned adequately. Ossa has increased the diameter of the brake cable, and this measure appears to have cured previous inconsistencies.

The exhaust system is neat, handsome, and quiet—it’s hard to imagine a better layout for a trials machine. The pipe swings to the left from between the frame down tubes, and squeezes inside the kickstart pedal close into the machine’s bodywork. An oval shaped muffler helps to keep the system away from the rider’s leg. The layout is so unobstrusive that, once astride the bike, the rider forgets it completely.

Telesco makes the Plonker’s front and rear suspension components. The front fork offers approximately 8 in. of travel—very long, even by trials standards. The fork action deliberately has been made soft, to absorb the moonscape type roughery scattered throughout the typical section. In this way, the fork soaks up jolts that might otherwise throw the bike off line. Maybe Ossa has gone too far, though. The fork telescopes approximately 2 in. merely under the weight of the rider, and the unit tends to bottom quite easily. The lower fork legs are formed of steel, rather than aluminum, a point which probably aggravates the bike’s somewhat heavy handling at the front end.

In design, the Plonker certainly offers a different approach to the task of building a trials machine. Its relatively heavy and robust construction at times handicaps its ability to be dodged through sections. Perhaps Ossa’s mistake lies in employing too many identical components on every bike in its range, rather than tailoring each machine to its individual purpose. The Plonker’s frame, for example, while fine for a motocross racer, is almost massive by trials standards. A lighter, single-downtube unit probably would have worked as well, or better. On the other hand, that delightfully strong engine will pull the bike out of all kinds of trouble. When the last section is closed, and the score sheets are tallied, there is no reason why a Plonker should not head the results sheet. [öl

OSSA

PLONKER

SPECIFICATIONS

$750

POWER TRANSMISSION

DIMENSIONS