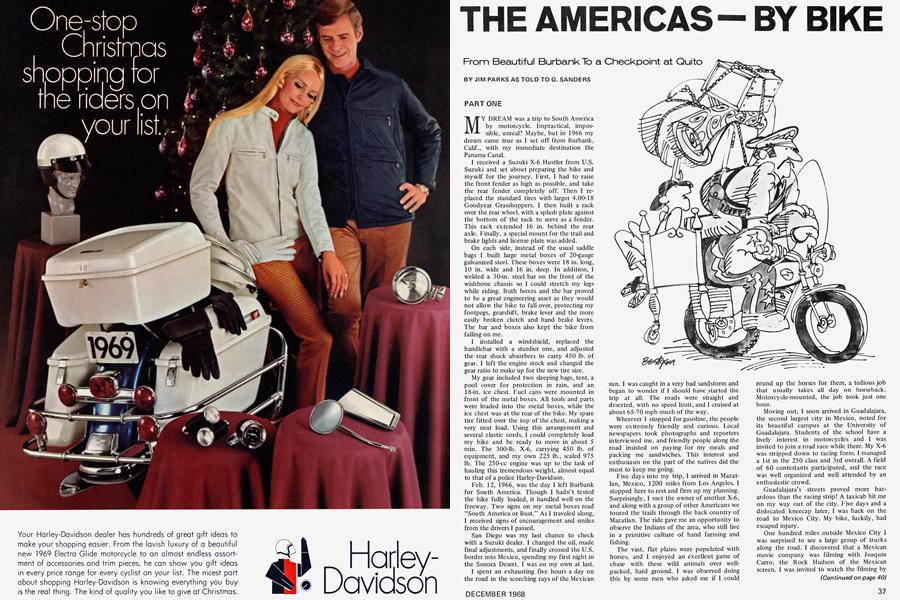

THE AMERICAS-BY BIKE

From Beautiful Burbank To a Checkpoint at Quito

PART ONE

JIM PARKS

G. SANDERS

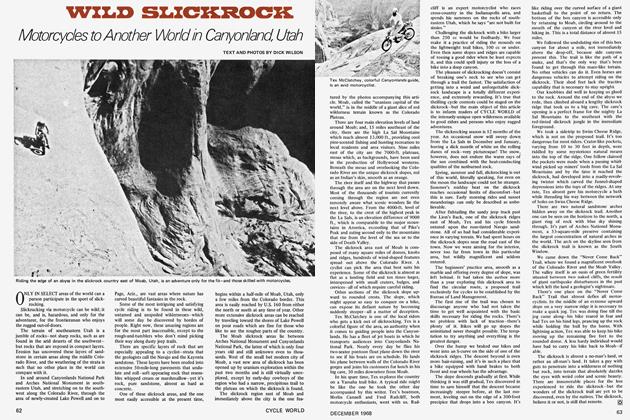

MY DREAM was a trip to South America by motorcycle. Impractical, impossible, unreal? Maybe, but in 1966 my dream came true as I set off from Burbank, Calif., with my immediate destination the Panama Canal.

I received a Suzuki X-6 Hustler from U.S. Suzuki and set about preparing the bike and myself for the journey. First, I had to raise the front fender as high as possible, and take the rear fender completely off. Then I replaced the standard tires with larger 4.00-18 Goodyear Grasshoppers. I then built a rack over the rear wheel, with a splash plate against the bottom of the rack to serve as a fender. This rack extended 16 in. behind the rear axle. Finally, a special mount for the trail and brake lights and license plate was added.

On each side, instead of the usual saddle bags I built large metal boxes of 20-gauge galvanized steel. These boxes were 18 in. long, 10 in. wide and 16 in. deep. In addition, I welded a 30-in. steel bar on the front of the wishbone chassis so I could stretch my legs while riding. Both boxes and the bar proved to be a great engineering asset as they would not allow the bike to fall over, protecting my footpegs, gearshift, brake lever and the more easily broken clutch and hand brake levers. The bar and boxes also kept the bike from falling on me.

I installed a windshield, replaced the handlebar with a sturdier one, and adjusted the rear shock absorbers to carry 450 lb. of gear. I left the engine stock and changed the gear ratio to make up for the new tire size.

My gear included two sleeping bags, tent, a pool cover for protection in rain, and an 18-in. ice chest. Fuel cans were mounted in front of the metal boxes. All tools and parts were loaded into the metal boxes, while the ice chest was at the rear of the bike. My spare tire fitted over the top of the chest, making a very neat load. Using this arrangement and several elastic cords, I could completely load my bike and be ready to move in about 5 min. The 300-lb. X-6, carrying 450 lb. of equipment, and my own 225 lb., scaled 975 lb. The 250-cc engine was up to the task of hauling this tremendous weight, almost equal to that of a police Harley-Davidson.

Feb. 12, 1966, was the day I left Burbank for South America. Though I hadn’t tested the bike fully loaded, it handled well on the freeway. Two signs on my metal boxes read “South America or Bust.” As I traveled along, I received signs of encouragement and smiles from the drivers I passed.

San Diego was my last chance to check with a Suzuki dealer. I changed the oil, made final adjustments, and finally crossed the U.S. border into Mexico, spending my first night in the Sonora Desert. I was on my own at last.

I spent an exhausting five hours a day on the road in the scorching rays of the Mexican sun. I was caught in a very bad sandstorm and began to wonder if I should have started the trip at all. The roads were straight and deserted, with no speed limit, and I cruised at about 65-70 mph much of the way.

Wherever I stopped for gasoline, the people were extremely friendly and curious. Local newspapers took photographs and reporters interviewed me, and friendly people along the road insisted on paying for my meals and packing me sandwiches. This interest and enthusiasm on the part of the natives did the most to keep me going.

Five days into my trip, I arrived in Mazatlan, Mexico, 1200 miles from Los Angeles. I stopped here to rest and firm up my planning. Surprisingly, I met the owner of another X-6, and along with a group of other Americans we toured the trails through the back country of Mazatlan. The ride gave me an opportunity to observe the Indians of the area, who still live in a primitive culture of hand farming and fishing.

The vast, flat plains were populated with horses, and I enjoyed an excellent game of chase with these wild animals over wellpacked, hard ground. I was observed doing this by some men who asked me if I could round up the horses for them, a tedious job that usually takes all day on horseback. Motorcycle-mounted, the job took just one hour.

Moving out, I soon arrived in Guadalajara, the second largest city in Mexico, noted for its beautiful campus at the University of Guadalajara. Students of the school have a lively interest in motorcycles and I was invited to join a road race while there. My X-6 was stripped down to racing form. I managed a 1st in the 250 class and 3rd overall. A field of 60 contestants participated, and the race was well organized and well attended by an enthusiastic crowd.

Guadalajara’s streets proved more hazardous than the racing strip! A taxicab hit me on my way out of the city. Five days and a dislocated kneecap later, I was back on the road to Mexico City. My bike, luckily, had escaped injury.

One hundred miles outside Mexico City I was surprised to see a large group of trucks along the road. I discovered that a Mexican movie company was filming with Joaquin Carro, the Rock Hudson of the Mexican screen. I was invited to watch the filming by Carro, who spoke English. I spent the next few days observing the movie-making, and the next few nights learning the dangers of too much tequila.

(Continued on page 40)

Continued from page 37

During the filming, the company encountered a problem with the herding of their horses. I explained my method to the company and was immediately challenged by one of the horse riders to a contest.

Three horses were released and the horsemounted cowboy rounded them up and returned them to their corral in 10 min. I felt confident that my steed could better his time, although my three horses seemed extremely spirited. Charging my 29 bhp out after real horses was a thrill. I accomplished the mission in 7 sec., to the dismay of a certain cowboy.

The producer asked me to round up some horses that had been running loose for the past two days. He was impressed with the handling of the cycle and the way in which I used the noise of the machine instead of yelling. Cracking the throttle, to bring the rpm very high, then letting the clutch out and choking the engine down to low rpm made a loud barking sound not unlike a very large dog.

After this demonstration of the roundup virtues of my motorcycle, the producer asked me to go to Mexico City to pick out a machine that could be used for the rounding up of horses.

Flying in a private plane, I arrived in Mexico City and started my quest for a suitable motorcycle. After a brief search, I asked to be directed to the local Suzuki dealer and found a T-10, 250-cc, pressed-chassis type motorcycle which would do the job. Returning to the movie site, I took my newlyobtained pesos and rode into Mexico City.

From Mexico City on through my trip I made it a point to go directly to the newspapers as soon as I arrived in a city. The publicity helped me find new challenges and interesting sidelights to color my already thrilling experiences in Mexico. While in Mexico City I was asked to appear on a television program, sort of a Mexican Ed Sullivan Show, to relate a little about my trip and my motorcycle.

Although I worried a little about the many miles I still had to cover, I again accepted an invitation to race my bike while in Mexico City and took 1st place in my class of the competition.

One of the motorcycle clubs there invited me to go to Acapulco, and on the way back to Mexico City after my stay, I was again hit by a car and thrown from my bike. Unprotected in shorts, the fall removed a great deal of skin.

A week later, I traversed the ultra-modern toll road from Acapulco to Mexico City and set out for Guatemala, through Vera Cruz and along the coast, avoiding the mountains.

Pulling into Guatemala City, I stopped at a small restaurant to seek information. I heard a siren and saw a jeep with a machine gun and six policemen come roaring toward me. The police grabbed me and took me to jail without an explanation. The cells of the jail were filled with motorcycle owners. Two days later I learned that a man on a black motorcycle had shot four soldiers in the back of a truck only two hours before I pulled into the city. The soldiers and police went through my gear looking for a weapon, even taking my pocket knife before releasing me with a note of clearance. This note proved a true salvation to me as I was stopped about every 20 min. in the next two days before crossing the border into San Salvador.

Eight hours took me to Honduras and five more to Nicaragua, where I observed a motocross meet on the President’s palace grounds. The competition was mainly among big European bikes, nothing like the scrambles races in the U.S.

In Managua, Nicaragua, I stopped at a traffic light and, before I could blink twice, I was surrounded by yelling, screaming children. I guess I was quite a sight with my American flags flying and mounds of gear strapped to a strange looking motorcycle. Before I could think, one kid grabbed a transistor radio off my handlebar and ran. I gave chase. Not more than 30 ft. away I realized my bike was left unattended. I turned around and saw my bike being attacked by the remainder of the kids. I ran back yelling and throwing my arms about, scaring the mini-bandits away. I knew of this old trick before and that just made me madder at myself.

The road to Costa Rica was broken, rippled pavement through steep mountains. The altitude created a loss of horsepower because of thin air. I made the crossing at 2 a.m. in pouring rain and sleet.

One of the major problems I had was to obtain gasoline in Costa Rica. High octane gas was not to be had, and the fuel that was available created carbon in the engine and a loss of power.

I left Costa Rica about 2 p.m., not realizing that I had an 11,000-ft. pass with a gravel and clay road ahead of me. In a torrent of wind and rain, I was making less than 10 mph. The mud caked in between my front fender and tire, causing me to fall. I finally was forced to stop and completely remove the fender. Worse, in the bitter cold, ice formed on my handlebar and windshield.

I stayed the night in a little general store and was greatly relieved to find that I had only 10 miles of uphill road ahead of me in the morning. However, the road still was wet and I had to stick with first and second gears to keep from falling. I took well over an hour to gain those 10 miles. The road I had been following was very lightly traveled; an occasional truck was all I ever saw.

I drove through the dusty little town of San Isidro and camped overnight before starting the last leg of my trip to Panama. The next day of riding was a relief as I finally hit paved road.

1 arrived in the Canal Zone the following day after a pleasant night of camping on a beach in Panama. I was surprised at the number of motorcycles in use in the Canal Zone by natives and Americans. Everyone seemed glad to have me stay. The warm welcome was just what I needed. The people in the Canal Zone were so receptive that I decided to stay two months. This time proved to be the most exciting, enjoyable days of my trip.

Before leaving Panama it was necessary to check road conditions to my next destinations, Colombia and Venezuela.

By consulting surveyors I learned there was no road to Colombia, just solid jungle. I was stuck because I had used most of my money already, and boat fares to Colombia were beyond my means. I began to think I might have to stay in Panama, not such a bad idea, but I had to keep moving.

It was at a local drag race that the idea hit me. I could make plenty of money organizing races if I had a place to hold the competition. The idea sounded good because local racing fans were eager for a well-organized drag race, because previous races were run by car clubs.

I contacted a couple of gasoline companies and the local TV stations and told them what I had in mind. I received permission to use an old, abandoned air strip, and completely organized a series of races. Oil companies put up small trophies, and the TV stations filmed the event. There was a large turnout, and I grossed a small jackpot, enough to finance my boat trip to Venezuela.

My first attempt to leave Panama ended in a rather interesting predicament. I was told how I could take a banana boat to a fishing village near the Colombian border, and from there a boat would take me to Colombia. As it happened, the banana boat took me 126 miles below Panama and left me and all my gear to be transported to Colombia by Indian dugouts. Of course I refused to trust my motorcycle and gear to a hollow tree trunk. There I was surrounded by curious, halfnaked natives, truly up a creek without a paddle.

Through my broken Spanish I learned from the natives that there was an American fishing resort on the other side of the mountains. I needed help, so I hired a guide and set out through 10 miles of steaming jungle. When I reached Club de Pescado de Panama, I contacted the owner. He hired me to overhaul boat engines until I was able to return to Panama. Two weeks later I was aboard the banana boat again.

Before leaving Central America for the second time, I completely dismantled my bike. With 13,000 mües on it, not one part needed changing. My motorcycle had held up remarkably well; it was still in good condition. I loaded the bike aboard ship and sailed for Venezuela.

As the Italian liner pulled out of Cristobal harbor, I gazed back at the flickering lights of Panama’s second largest city. I wondered if South America would be the challenge that Central America had been. Or, if it would be too much for me and my motorcycle.

It was early morning when I first saw lights shining from La Guaira, Venezuela. Excitement gave me the shakes as the boat docked and my motorcycle was unloaded.

I had to wait a day for customs to clear my motorcycle, so I spent the night on the dock with the locals, picking up a few hints about Venezuela.

From La Guaira I took the ultra-modern highway to the capital city, Caracas. Rising 3000 ft. in 12 miles, I reached the capital in 20 min. This highway is the beginning of the Pan-American Highway for South America. Caracas is a beautiful city in the mountains— modern. I was impressed with the semi-freeways that lace the city and country together.

As usual, I went to the newspapers and arranged for publicity. A few days later I was asked to appear on television and talk about my exploits. The Suzuki dealer of Venezuela had contacted me for advertising purposes and arranged for me to stay at one of the most luxurious hotels in Caracas. I might mention that the late Jayne Mansfield was staying at the same hotel. I had a chance to talk to her and I did get her autograph.

I appeared on television for two weeks straight on behalf of Suzuki. I explained my trip and bike and told of past experiences. My lectures were in Spanish—and that required hours of practice.

I spent most of my time touring the countryside, visiting oil fields, and driving through villages around Caracas. The beach at La Guaira provided a relaxing spot to soak up sunlight on the Caribbean Sea.

I left Venezuela by the mountain highway and as I got closer to Colombia the road worsened until it was completely non-paved trail. My trip through Venezuela was rather uneventful except for the gasoline company contract which provided fuel for the remainder of my trip.

People had warned me about the dangers of traveling in Colombia, but I had thought these were just things people read about and see in movies. I didn’t heed the warning. After clearing customs, I stopped to ask directions in Cucuta and as usual attracted a crowd of curious children. Thinking this would make an interesting picture, I reached for my camera. It was gone. I spent the next two days chasing about Cucuta on tips from witnesses who said they had seen a little boy going through my gear. The search was tiring and of no avail.

I left Cucuta and aimed for Bogota, 15,000 ft. in the Colombian Andes. As I climbed higher into the green mountain range, the roads became worse. As the roads deteriorated, I logged fewer mph and as I got higher into the mountains the air got thinner, which decreased my engine’s power. All in all, the trip to Bogota was a struggle, a distance of 900 miles. From Caracas to Bogota is 2400 miles. I made it in 12 days of rain, sleet, and rugged riding. The journey was hard on me and even harder on my bike, but both of us kept going and came through in surprisingly good shape. In fact my bike was in better shape than I was, for the cold weather had cooled the engine and enabled me to ride for long hours at a time.

Bogota is at 9500-ft. altitude in the Andes. It was raining as I pulled into the city. All I thought about was how nice a hotel room would be.

The following day, I set about touring the city and checking up on local motorcycle clubs. Of course, I visited the newspaper and had my picture taken. At the newspaper office I met a girl who was an advertising model for a brewery. She asked me if I would like to pose in pictures with her. This new job occupied me for two weeks and gave me the money I needed to continue my trip. It wasn’t that I was the modeling type, it was just something about my 225-lb. frame with some of it hanging over my belt, which made me look like a beer drinker.

My experiences with the beer company gave me a preview of many of the countries I would be traveling through in the months to come. We flew from place to place—and the bird’s eye view was impressive.

Leaving Bogota was all down hill and getting warmer all the way. I rode about three hours, then was halted by a flat tire. All my patches were soaked with oil and were of no use, so I had to catch a bus to the nearest town to repair my tire. I paid a couple of passersby to watch my bike until I returned. The bus I took looked as if it would hardly make it down the mountain, but nevertheless off I went, surrounded by local people, chickens and fresh vegetables in baskets. A few minutes after we were under way, a horse dashed out into the road. Instead of stopping, the bus driver hit the horse and ran over it, stopping a few feet away from it. Before I could get off the bus for a look at the poor horse, the passengers had jumped off and butchered the horse with their machetes. Every man, woman and child was loaded down with strips of meat, blood dripping and coloring their clothes and bodies. As they boarded the bus once again, everyone exclaimed their surprise at such good fortune. I sat stunned. By the time we reached the town, the stench and flies were overwhelming. I had my tire fixed in no time and was back on the road again. I drove on to Ibague and spent the night in a hotel.

The next morning as I was touring the city I thought I saw a policeman riding a motorcycle similar to mine. Later that day I saw him again and, sure enough, he was mounting a Suzuki. I learned from him that the police department there had just received 22 Suzuki T-lOs rigged for police work. He seemed awkward on the bike and told me that they were having trouble with them because no one knew how to ride the new two-strokes. I contacted the chief of police and a few days later started a school for motorcycle policemen. That being the first year for motorcycle patrols in Ibague, I had to teach each man how to shift gears and handle the bike in fast, hard driving. I was made an honorary policeman and given a token of a few dollars by the mayor.

I was in a hurry to get out of Colombia as I had spent more time here than I intended. I was back on the road again, heading for the border of Ecuador, hoping to make it by nightfall. The cold, rough riding slowed me down so much that I could only get to Pasto, 60 miles from the border, before dark. I kept going until it was too dark to see for safety. After finding a clear spot by the road, I bedded down for the night. The icy wind bit through my clothes and I felt as if I were freezing to death. I decided about 3 a.m. to get back on the road because I couldn’t get to sleep. The wind was blowing 40 mph in the direction I wanted to go, so I tried staying at 40 mph to reheve the cold, but to no avail. I rode for about an hour when I came upon a gas station and stopped to refuel.

It is a known fact in Colombia that service station attendants are the easiest going people in the country. A person has to fill his own tank, then practically drive away before they’ll come out and take your money. In this gas station, however, I was surprised when a man hurried out of the small garage and came toward me. I was really surprised when he stuck a gun in my ribs so hard that I fell off the bike. Just my luck to pull into a gas station as it was being robbed. I was very scared and he was very drunk. He pushed me around a little and then, after taking my money, he locked me in the bathroom with the owner. It took us nearly two hours to break out. It sounds strange that a guy my size should take that long breaking out of a bathroom. However, in Colombia when they build a public restroom, they build it strong and sturdy because the Indians try to break in. The sinks make great stewpots.

I was greatly relieved to find most of my gear intact and my bike unharmed when I finally got out. The bandit did relieve me of my new camera which I had just replaced in Bogota. After giving my story to the police, I left without hope of retrieving my gear.

I had a small sum of money hidden in my battery case for just such an emergency. It came in handy as I made Ecuador in two hours and needed a few pesos here and there to expedite customs red tape. I also had a newspaper clipping and picture taped to my windshield to help me explain to officials what I was doing.

I had learned that the next 600 miles would be no different from the rough mountain highway in Colombia. I found that the road was paved with huge cobblestones.

In the afternoon, I again was stopped by a flat tire. I thumbed a ride on a lumber truck headed for Quito, Ecuador, where I could fix my tire, respoke and straighten my rim. I loaded my bike aboard and off we went. About 100 miles from Quito, we were stopped at a customs checkpoint. The truck was pulled aside from the line of other trucks and completely unloaded. The last layers of boards were stacked about 10 high and were nailed together. The boards formed a sort of a crate, and inside were black market clothes and guns. The truck was relieved of its illegal burden and the real lumber was restored. The officials explained that I was just picked up as a decoy to help get through the checkpoint. I fixed the flat myself at the checkpoint and rode into Quito.

I reached Quito at sunset and did a brief tour of the beautiful capital city before finding a place to sleep that night .(Continued next month.) [o]