MONTESA COTA 247

CYCLE WORLD TRIALS TEST

Simple Design for a Winner's Weapon

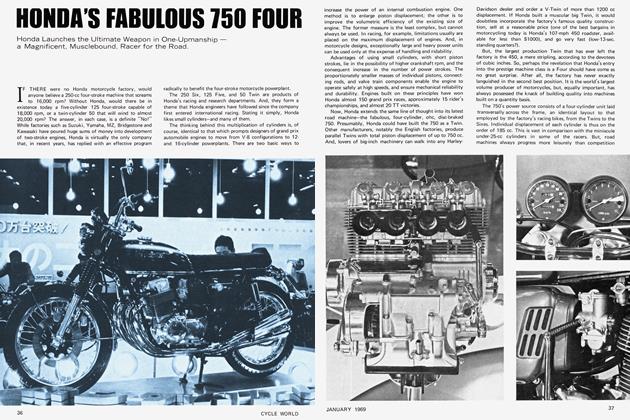

THREE MINUTES in the saddle of the new Montesa Cota 247 will be sufficient for a trials rider to decide that here is a superlative motorcycle. Give him another 30 minutes of riding and critical inspection, and the odds are very favorable that he will vote the newcomer one of the top three trials bikes in the world. Some will dispute the Montesa’s superiority, for motorcycles are very personal items, and what pleases one man, may annoy another. But CYCLE WORLD testers feel confident that the majority of trialsmen will agree that the Cota is virtually the ultimate weapon in its field.

That Montesa can launch such a magnificent machine reflects handsomely on the factory’s engineers, for, only recently, the company was among the backmarkers in trials competition. Bultaco, Greeves, Ossa and Cotton were the bikes to buy. Suddenly, positions are reversed, and Montesa is among the pacemakers.

Simplicity is the keynote of the Cota’s success. The factory has mounted a single-cylinder two-stroke engine, fairly light in weight and compact in outer dimensions, into a singularly non-complex frame. All other components are designed to function adequately, but unobtrusively-and nothing more. The fuel tank and seat are an example of this line of thought. On a trials bike, these components should encompass light weight and narrow girth, the latter to enable the rider to clamber about the machine without interference. The Cota employs a one-piece tank and seat unit formed of fiberglass, which insures lack of weight, and which is as slender as any rider could demand. Not an inch of fiberglass is wasted. The unit descends just low enough at the sides to protect the air filter from mud and provide a sound-deadening chamber for the exhaust system, and terminates abruptly at the rear of the seat. The tank holds only 1.7 gal. of fuel, but that is all that will be needed for trials competition. The unit does its job—without frills.

Frame design follows the identical theme. Single top tube and downtube are employed, with liberal gusseting at the steering head. In front of the crankcase, the downtube divides into two smaller diameter tubes which serve as engine cradles, and provide the additional benefit of greater engine protection than a single tube could offer. These tubes loop upward behind the transmission to join the toptube. Additional small diameter tubing carries the seat and rear mudguard. The swinging arm pivot is carried in tabs welded to the rear frame loops, and, just ahead, another crosspiece serves as a strengthening brace and as a mounting point for the engine.

Spring-loaded folding footpegs are bolted directly to ears that project from the gusseting that carries the swinging arm pivot—no fussy additional tubing is required to support them. The pegs themselves are simply short tubular fixtures that incorporate three ridges to provide footgrip. Again, plain design means a bonus in light weight and lack of hamper.

Alloy wheel rims and fenders are musts on a competitive off-road machine, and the Cota includes these items in its specification. Further proof that the factory is serious about production of a trials bike without compromises, lies in the lack of a lighting system. Observed trials machines are so specialized these days that no one cares to run them on the road, and, any rider set on winning, discards lighting, even if it is supplied. Montesa has saved the additional cost of lights by eliminating them before the drawing board stage. The rider is saved the job of storing them in a dusty corner of his garage.

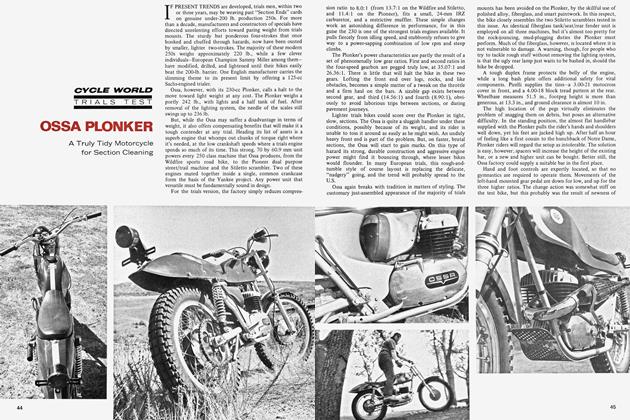

This kind of no-nonsense thinking has brought the Cota’s weight down to a Spartan 222 lb., in a ready-to-ride condition. In fact, the bike is so finely balanced that it feels lighter still when guided through a section. Of all trials bikes, the Cota probably handles with the greatest ease as a result of this combination of lightness, balance, and slender, Twiggy-like dimensions. In trials, as in all motorcycle sports, the best tactic is to let the bike perform most of the work, yet there are certain sections that also demand musclepower from the rider. On these occasions, a rider can physically manhandle the Cota without bursting a blood vessel.

The way in which the front end can be lofted over barriers is one of the Cota’s outstanding handling qualities. The front wheel soars skyward with contemptuous ease—but only when the rider wishes it to. Otherwise, there are no unexpected wheelstand antics. Even when the front tire wags four feet in the air, a delicate forward transfer of weight and a relaxation of the throttle grip floats the wheel to earth.

Body lean is one of the trials buffs major tricks to offset adversely cambered slopes, and this is where the Cota’s slender lines save marks. The tank and seat are so narrow and low that the rider can swing into extreme angles, in order to place weight where it’s most needed. Moreover, there are no awkward projections or lumps on the bike’s waist section that could hinder leg movement.

Montesa, in the past, fitted Telesco front forks to its trials mounts, but the Cota features the factory’s all-new fork, designed and built by Montesa personnel. It incorporates double-acting hydraulic shock absorbers that perform a fine job of damping. Suspension travel is ample, and the unit refuses to bottom, even on the roughest of bumps. To match the new fork, Montesa also has provided a fine set of fabricated triple clamps. During development of the Cota, the factory changed steering geometry no less than 11 times. The final result provides superbly light and accurate steering. Telesco suspension units are retained at the rear; they also perform flawlessly.

Both brakes are contained in full-width hubs. The performance of the front unit provides ground for the only serious criticism of the Cota’s handling. The front brake sometimes locks suddenly and unexpectedly during descents on looselysurfaced or adversely-cambered gradients. The problem could be eased by chamfering the brake linings. The rear brake, however, proved effective enough to be used safely under all conditions. The brake pedal is a masterpiece of neat construction. Its body consists of a conventional piece of tubing, but the tip is formed of a small-diameter tubular trunk, pointing vertically, with a serrated upper circumference, to provide a non-slip surface. This rounded tip features no forward-pointing edges that can dig into shrubbery. Instead, the pedal will glide past everything from rocks to tree roots. As an additional move to keep the Cota’s profile slim, both brake and gear pedals are blended tightly into the transmission cases.

In the engine and transmission department, the major improvement to the Cota, compared with previous Montesa trialers, is the use of five speeds, instead of four, in the gearbox. The additional pair of gears means that the maker has to make less of a compromise in selecting ratios. First, second, and third gears are, of course, the ones used in tackling sections, and all are well matched so that there is always a perfect ratio for every type of hazard. Gear selection, with a short lever on the right side, is crisp and swift. There is no chance of missed changes. The lever actually could have been still shorter, as average size boots are not quite long enough to reach its tip.

Factory claims for engine output now call for 19 bhp at 6500 rpm, whereas the previous Montesa trialer was said to develop one bhp less, at 5500 rpm. Otherwise, the two units are almost identical. Ball bearings support both ends of the crankshaft, the transmission shafts, and the clutch. The small end of the connecting rod turns on a needle bearing.

In terms of low-speed lugging power, the Cota’s engine may not be the strongest in the business, but it is not far behind the best. And, the bike’s graceful handling characteristics almost cancel out any disadvantage it may suffer where power is concerned. Aided by smooth carburetion from the IRZ unit, the bike will plonk along at a speed low enough to tackle the most “nadgery” of going. If the throttle is suddenly snapped open, massive flywheel effect insures that the engine delivers a steady surge of torque, rather than a vicous stab of power. Montesa builds in this smooth supply of power by installing an extra flywheel in the primary case, in addition to the usual crankcase flywheels, and the big Motoplat flywheel on the timing side. This modification helps to make a slogger from an engine that, in motocross trim, delivers some 30 lively bhp.

The bore size of the IRZ carburetor has been enlarged from 22 to 24 mm, though the long metal connecting stub between carburetor and cylinder barrel is retained. Ignition power is supplied by a flywheel magneto.

The Cota’s stand-up riding position offers comfort for riders of almost any height. A 6-footer flings the bike about as effortlessly as a 5-ft., 6-in., rider. Footpeg-to-handlebar relationship is perfect, while the bar itself is almost straight, and neither too high nor too low. The seat is a mere triangular pad-another reminder that Montesa makes no compromises with this new bike.

The factory deserves special praise for three ingenious items on the Cota. In the first place, it was some time before test riders started thinking about the exhaust system. Then, it took a few more seconds before they actually found it. The reason is that the layout is so unobtrusive that it remains invisible to the eye, and not felt by any part of the body, unless the rider makes a special effort to track it down. He eventually finds that Montesa has cleverly tucked the silencer beneath the seat! The large diameter pipe curves upward from the cylinder barrel, disappears under the fuel tank, and is never seen again, except in the form of an outlet about 1-in. long peeking from behind the seat. The system is so simple that one wonders why every manufacturer doesn’t adopt it. Hidden in that under-seat chamber, the silencer is kept away from the rider’s legs, and the noise level is effectively deadened.

Equally unusual is the lubrication system for the rear chain. The drive side rear fork does duty as an oil tank, and incorporates a needle valve that meters lubricant onto the lower run of the chain. The rate of delivery of this constant-flow system is controlled by a screw, while the filler cap for the tank is located at the forward end of the rear fork. The oil supply can even be shut off completely, if the rider so desires.

The treatment of the speedometer is equally neat. It’s small and light, and bolted to a lug halfway down the lower stanchion of the right leg of the front fork. Mounted behind the fork leg, it still is easily visible to the rider. But this location avoids the addition of weight and bulk to the steering head, while the speedometer cable runs in a brief, direct line down to the front axle. The disadvantage to this location is that the unit could easily be broken in a spill. Also, the test bike’s speedometer was marked in kph, rather than mph.

Riders of the caliber of French trials champion Christian Rayer, Spanish ace Pedro Pi, and Englishman Don Smith, who monopolized the European Trials Championship before the series was given that official title, have helped to develop the Cota to the magnificent machine it is today. A sum of almost $900 is not an excessive price to pay for that much experience, and that much motorcycle.

MONTESA

COTA 247

$895