HONDA 350 FOUR

Technical Analysis

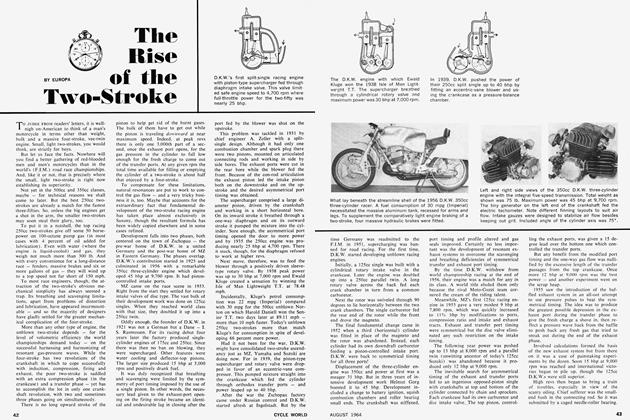

EUROPA

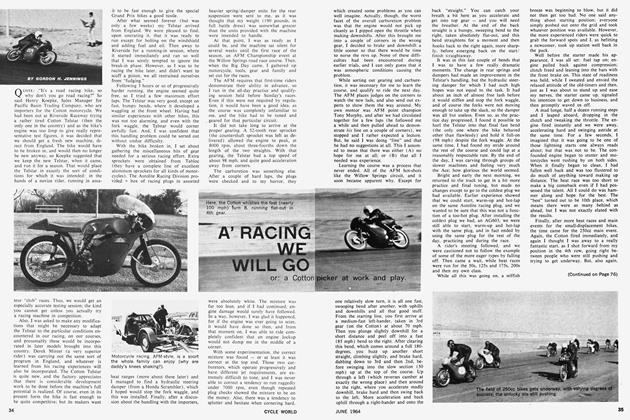

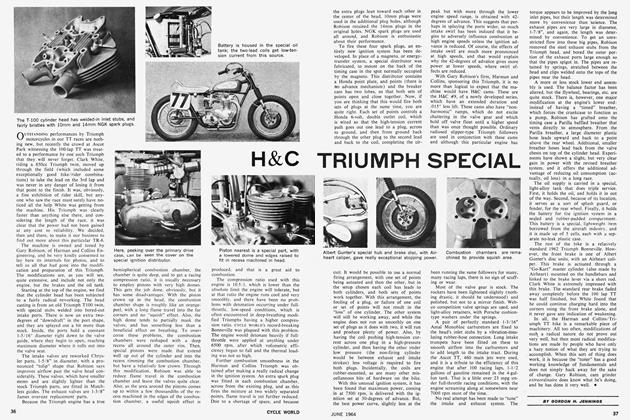

WITH HONDA scooping seven world championships in the last three years, it seems incredible that their debut on the Western race scene was as recent as 1959. They came with a team of 125cc (44 x 41 mm) twins — the more famous 250cc fours weren't seen in Europe for a further year; and the full-blown 350cc machine pictured here has been on the go for only 18 months.

What seems even more unreal in view of Honda's stupendous achievements is that their European debut was greeted with polite derision. Sure the bikes were dependable — but oh, so slow. As witness the results of the 125cc Isle of Man T.T. in 1959: four of the five Hondas finished sixth, seventh, eighth and 11th, the other fell.

Everyone agreed their workmanship was second to none. But their guillotine-type throttle slides were way behind the times. So was the use of a one-inch larger wheel at the front than the back. Their front forks were of the pivoted type that had been ousted by telescopies on all Europe's best solos.

As for power, how could Honda hope to be competitive with four valves per cylinder? Had not Europe's ace designers abandoned four valves nearly 30 years earlier? Uh-huh, was the smug conclusion, the Japanese have too much to learn.

When they returned to the Isle of Man the following year, there was little evidence of the rate at which they were learning. In the 125cc T.T. they took all places from sixth to tenth inclusive, while their tail-ender came 19th. Again, an admirable show of reliability but hopelessly short on speed. Why, their best man came no nearer than 5-1/2 mph to the winner's average.

So it was natural that chief interest fell on the three four-cylinder machines the factory entered in the 250cc T.T. There again, though, they were rated more amusing than threatening. At that time the world's best one-two-fives had only one cylinder, so two cylinders were surely enough for a two-fifty?

Moreover, those early Honda fours were reckoned far too bulky for the lightweight class. Carrying six pints of oil in a sump at the base of the crankcase set the engine fairly high. Then the 30-degree forward inclination of the cylinders, together with a steep downdraft angle for the carburetors, cocked the intake trumpets up like the funnels on an ocean liner. And since those trumpets were unusually long, there was a high arch in the bottom of the massive tank - which looked like an overgrown hump on a camel.

Unlike some of the smaller Hondas, though, the four had telescopic forks and equal-size wheels. But use of a hydraulic steering damper cast suspicion on the handling, because until then these devices had been called for only for sidecar racing.

The four-cylinder engine was virtually a double-up of the six-speed twin, though the two overhead camshafts were driven by a i train of spur gears in the middle instead of the shafts and bevel gears of the smaller engine. But in the 250cc T.T. the story was again one of ample stamina but insufficient speed. All three machines finished — fourth, fifth and sixth. And though the factory had wisely engaged some top British riders, their fastest finisher — Australian Bob Brown — was nearly 4-1/2 mph down on the winner for average speed.

No, the Isle of Man T.T. remained the most exacting criterion of raceworthiness — and there was nothing in the results to send Europe's top race designers scurrying back to hone their pencils. As the season wore on, Honda riders reported tantalizing bursts of really competitive speed. But it was never consistent. For no apparent reason top revolutions would suddenly drop by 1,000 or more. Peak revs were a hitherto unheard of 13,500 rpm and if a rider should miss a gear, the engine could whine up to 17,000 rpm before the valves started to float. But some elusive cause was preventing the engine from holding its peak.

Thus for two years Europe's top lightweight race teams were lulled into a comfortable assumption of invincibility. Had they but known it, their long years of smug self-satisfaction were well and truly ended. When Honda came back for the 1961 season the carburetors had conventional cylindrical throttle slides. Gone were the long trumpets and the downdraft intake angle. Ignition was by the energy transfer system, with a low-tension generator feeding current to separate high-tension coils. On the four (though not on the twin) oil was carried in a four-pint tank under the seat. The engine had been lowered, the sides of the fairing united by a belly panel and the frame spine changed from a single large-diameter curved tube to a duplex arrangement.

Came the Isle of Man T.T. and the Honda teams literally overwhelmed the lightweight races. First, second, third, fourth and fifth — that's how they finished in both the 125cc and 250cc events. Without tarnishing their reputation for mechanical reliability, they had found a new turn of speed and the consistency at peak revs to back it up.

Their dominance of the 250cc race might have been even more sensational, for Scotsman Bob Mclntyre, the team's unchallenged ace, was put out by a last-lap engine seizure after leading handsomely from the start. The revised oiling layout was not clear of its teething troubles and the engine had leaked dry. But even with an oil-slicked back tire Mclntyre had knocked the lap record up to an unbelievable 99.58 mph, a mark which has stood, for three years. Those crushing T.T. victories set the pattern for the rest of the 1961 season. At the finish Honda ran off with two world championships: Australian Tom Phillis was 125cc king and England's Mike Hailwood 250cc.

Nineteen-sixty-two for Honda was a year not only of consolidation but of expansion, too. Luigi Taveri, the dark and diminutive Swiss, won them another 125cc title while Jim Redman — hardbitten London-born Southern Rhodesian — kept the 250cc crown in the Japanese camp.

But so often had their 250cc winning speed topped that for the 350cc race at the same meeting, that they decided on a serious invasion of the 350cc class — first with an engine bored out to 285cc, then with a full-scale three-four-nine measuring 49 x 45 mm. On those machines Redman added the 350cc title to the Honda collection, thereby ending a fouryear MV Agusta monopoly.

(Continued on Page 71)

Although the factory was preoccupied with its 12-cylinder car racing engine last year, Redman managed to retain his two titles. But in the 125cc championship the Honda twins were eclipsed by the Suzuki two-strokes. So for the last grand prix of the season, in Japan, Honda brought out a 125cc four — was robbed of victory only by Jim Redman's gear pedal coming loose on its serrated shaft. As things stand at present, therefore, Honda have a 125cc four turning out 27-28 bhp, a two-fifty giving 48 bhp and a three-fifty with 52 bhp. And since they have achieved these remarkable outputs with four-valve cylinder heads and unprecedented rpm rates, the old charge of "copyists" is clearly out of date. Indeed the tables seem to have been turned; for car as well as motorcycle race designers in Europe are switching to four-valve heads. And in Detroit, Fords have done the same with their Indianapolis engine.

Clearly, when Honda took up racing their engineers paid more attention to fundamental principles than to tradition. They realized that since the F.I.M. formula limits engine capacity and prohibits supercharging, the road to more power inevitably lies thru higher rpm rates. That way the engine can inhale and burn its fill of air more often. It was no secret that safe rpm rates in European racing engines were limited by the destructive inertia forces that broke connecting rods and pistons, wrecked big-end bearings and gave rise to valve float. The logical answer? More and smaller cylinders, more and smaller valves.

Engineers argue hotly as to whether two valves or four give better cylinder filling and scavenging, but after Honda there can be little doubt which has the higher power potential and the greater safety margin in the event of inadvertent overrevving. When each valve weighs less than half an ounce — and only three-quarters of an ounce even with all its attendant reciprocating paraphernalia - two helical springs can easily keep it under control well beyond maximum-power rpm.

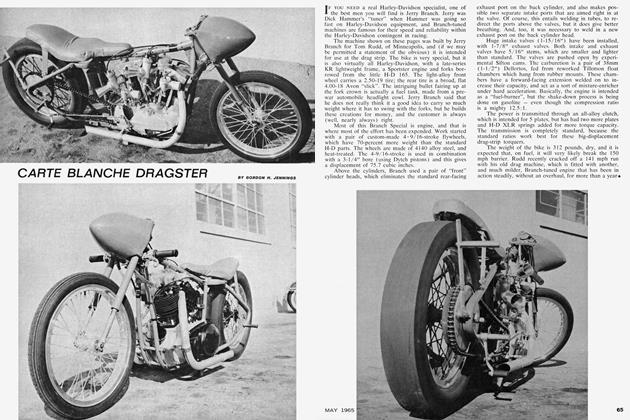

As a bonus, the four-valve layout leaves little choice for spark plug position but the middle of the head — which is the best possible location since it cuts flame travel to a minimum and avoids trapped pockets of unburned gas that might detonate. Basically, of course, all three sizes of engine conform to a similar pattern. So why don't we take a closer peek at Jim Redman's 145 mph three-fifty which is the subject of the accompanying pictures? Let us start at the top.

Cast in one piece, the aluminum cylinder head has iron skulls for the combustion chambers; these are of pent-roof shape so that each pair of valves is parallel. Angle between intake and exhaust stems is about 80 degrees. Valve head diameter is approximately 7/8 in., the intakes naturally being slightly larger than the exhausts. Giving a compression ratio of 10 to 1, the piston crowns, too, have a pent-roof form, closely matching the ¿ylinder heads. At the from and rear eçlges are flat, segmenj-shaped squish areas. All ports lie at 90 degrees to the cylinder axis, plumb on the fore and aft diameter; they are divided by knife-edged walls.

The four Keihin carburetors are mounted in rubber. There are no closing springs for the throttle slides; they are operated by a drum and two cables in the middle of a cross shaft. Jets are submerged in the float bowls. Four ball bearings carry each camshaft and the lobes actuate flat-topped hollow tappets; though maximum power comes at 12,500 rpm, Redman says he has seen 16,000 rpm on the tachometer without any sign of valve float.

The cylinder block, too, is a single casting integral with the top half of the crankcase. The joint with the bottom half lies horizontally across the axis of the five main bearings. Since the connecting rods have roller-type big-end bearings, the crankshaft is a built-up affair. A gear in the middle of the shaft distributes the drive through an intermediate shaft to the camshafts, the clutch (on the right-hand side) and the ignition generator (above the gearbox). The two double-ended ignition coils are taped to the frame tubes in front of the oil tank.

As on the 250cc machine, there are six speeds (the 125cc four has eight). All gears are indirect, the clutch being mounted on one end of the input shaft and the chain sprocket on the opposite end of the output shaft.

Honda has experimented with numerous frame layouts but in all cases the power plant has had a structural function. In this case the frame is basically duplex with the addition of a bracing tube behind the steering head.

The gas tank is strapped down on rubber pads on the low-level top tubes. Tanks range in size from 2-1/2 gallons to ten according to race length. Gasoline is restricted by the F.I.M. regulations to pump grade, oil is a synthetic racing grade, viscosity S.A.E. 20 (or S.A.E. 30 in very hot climates). Mounted on 18-inch aluminum rims, the tires are of minimum permitted sections - 2.75" front and 3.00" rear. Tread rubber is the latest high-grip synthetic mix. Front and rear brakes alike are cable operated. Described by the widely experienced Bob Mclntyre as the best ever, the well ventilated front brake is a duplex affair with two leading shoes on each side in 8-1/4 in.-diameter drums.

To suit individual preferences, the brake and gear pedals can be arranged on either side. Redman's machines have the linkage for a right-side gear shift. At nearly 2-1/2 miles a minute, air drag is a major problem; to minimize frontal area, the Honda's aluminum fairing is a very close fit at the engine sides. Design is ever a compromise. A four-cylinder engine set across the frame guarantees a permanent headache for the development engineer aiming to combine safe cornering clearance with the low center of gravity needed for slick handling. The problem gets more difficult as new tread compounds give usable grip half-way up the tire walls. But with all that silky power and proven dependability, Honda will take a lot of persuading that any other type of engine is worth serious consideration. Jim Redman's 350cc crown at least is pretty firmly jammed on his head.