(TECHNICALITIES)

GORDON H. JENNINGS

FOR REASONS that are not really clear, Americans tend to think of England's speed-tuning wizards as being some sort of supermen, privy to all manner of secrets not known to mere mortals. And, to complete the picture, there is a regrettable tendency in England to think that the barbarians across the Atlantic are still operating on a rather primitive level. Thus, men like Francis Beart and Paul Dunstall have acquired a reputation for being able to work magic on motorcycles in both England and her ex-colonies.

Some of the reputation is well deserved. Both of the men just mentioned have produced some remarkably rapid roadracing machines, and their services are much sought after. But, we have tuners here that are every bit as good, or better; it's just that they have not received the publicity that has been accorded their British counterparts.

In point of fact, I rather suspect that our better tuners are, by and large, doing a better job of super-tuning engines than anyone in England. This is not because we Americans are inherently more intelligent, or more clever. Being a complete hodge-podge of ethnic strains k would be presumptuous of us to claim any particular inborn traits. The simple fact is that we have the sort of flourishing economy and technology that makes available a tremendous variety of advanced materials and processes at a relatively low cost. Because of this, any tuner who has even limited (for us) financial backing can afford to "use metals such as magnesium and titanium, and will be able to employ all manner of special precision machining operations. Also, the tuner will be able to select many special components from the catalogues of our suppliers of speed equipment. This sort of thing is in relatively limited supply in other countries. A good example of this is afforded by our racing valve springs, which are made of alloys, and through manufacturing processes, that are utilized only in the aerospace industry in England. And, of course, whatever they have that is worthwhile is being imported into this country in quantity, so that in the end, we get the best selection of everything in motorcycles.

Finally, our tuners have the overwhelming advantage of dynamometers, without which development work on a new engine is enormously time consuming. Here, there are a great many shops equipped with dynamometers; in England these instruments are rarely seen outside the major factories. Of course, eventually one may achieve the same results through careful track testing, but that way takes much longer than is the case when the tuner has all the equipment he needs.

(Continued on Page 14)

I do not wish to get involved in a hassle over the relative merits of British and American racing motorcycles, as there is not enough solid evidence to allow any firm conclusions. But I do think it is safe to say that the English have very seriously underrated American capabilities in this area. This was to be seen, in no uncertain fashion, at the recent AMA Daytona road races. The Berliner Corporation ordered a batch of race-prepared Norton twins from Paul Dunstall, which was a logical course of action, as Mr. Dunstall has demonstrated an ability to make production-type Nortons into firstrate road racing equipment.

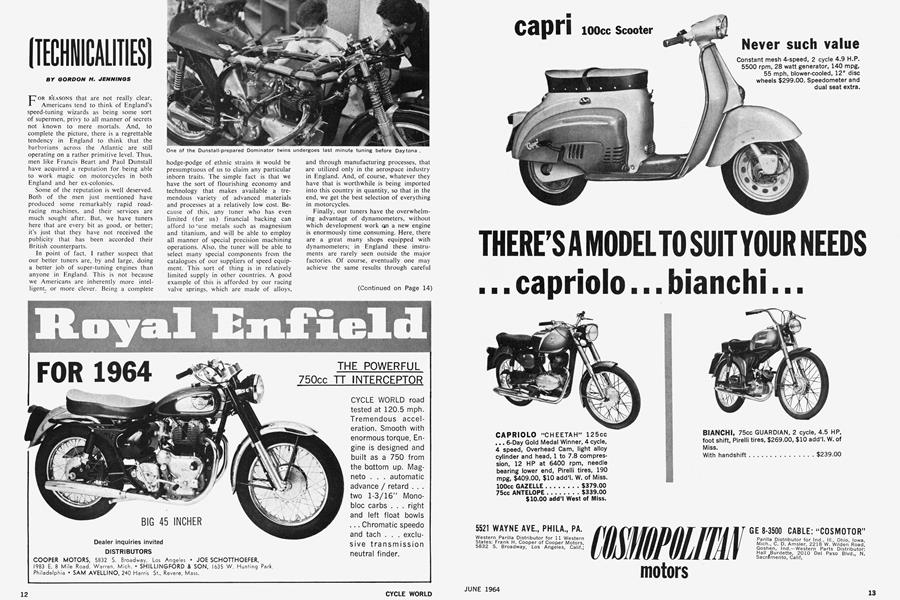

When word got out that these specially prepared Nortons were to run at Daytona, everyone assumed that they would be the machines to beat, and I daresay a lot of the entrants at that race were a bit dry of mouth at the prospect of such formidable opposition. What really happened, as is now history, was that the Dunstall-tuned Dominators were absolutely swamped. The Norton riders were able to use to good advantage the superb handling of the machines, and by forcing very hard through the turns were able to make a reasonably good showing; but these Nortons were noticeably down on power, compared to other well-prepared bikes there. In the end. the talented Frankie Scurria was to bring home 3rd in the amateur's race, and might have done better but for a carburetor that came adrift, and that was about the best any of the Nortons was able to do. Dick Mann's machine had its engine expire, and AI Gunter was never really in the hunt.

From all this, one might conclude that either the Norton motorcycle hasn't the potential for racing; or that Paul Dunstall doesn't know a wrench from a hammer. Both conclusions would be wrong. The Norton, in racing or otherwise, is a very fine motorcyle; and Dunstall is a very talented tuner indeed. Unfortunately, Dunstall appears to be a better judge of machinery than men. He quite simply failed to appreciate the talent of the opposition.

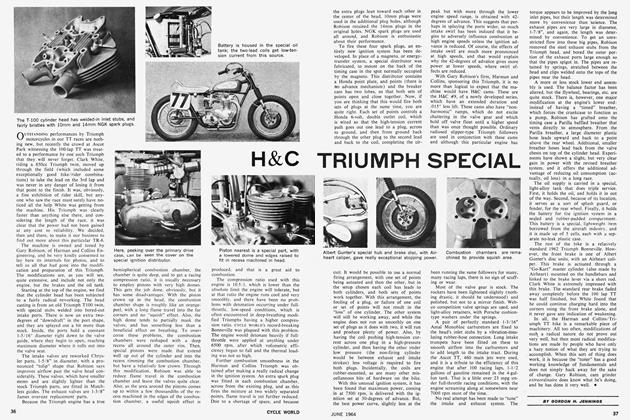

There are reasons for this lack of appreciation, obviously. No one. who hadn't seen it with his own eyes, would believe that out-dated long-stroke sidevalve engines would develop so much power, or turn so many revolutions. Another big shock for the English was the performance of our modified Triumphs. Triumph's 5()()cc twin is a very popular racing bike here, but little is being done with it in England and they find it hard to believe that the engine will run reliably at 9000 rpm, which it will with a few relatively minor modifications. Just as important, the engine will deliver a lot of power at these very high crank speeds. In England, tuners rarely attempt to turn even overhead camshaft engines that fast.

(Continued on Page 16)

Obviously, the best Triumph at Daytona was that ridden by Gary Nixon inlo second place. This machine was "tuned" by Cliff Guild, the relatively unknown but extremely talented Chief Mechanic at TriumphBaltimore. Combining careful assembly with special intake valves, valve springs and collars, cams, reworked porting and a "free-breathing" crankcase, Guild produced an engine that had enough power, at astronomical crank speeds, to run with the 50-percent larger flat-heads. He claims not to have done anything remarkable to the engine, but the results are most remarkable. Incidentally, one of the small touches Guild employed was to paint the engine a dull black. He says that this brought the oil temperature down noticably.

Incidentally, I would like to mention that it is likely that the oil supply tank does very little to cool the oil. Oil inside the tank is cooled only when it reaches the walls, and in practice, a layer of cool oil forms on the inside of the tank walls that fairly effectively insulates the rest of the oil supply. It seems probable that much of the heat leaves the oil as it runs down the walls of the crankcase, which are relatively cool, before it is picked up and pumped back to the reservoir.

After capturing a record at Bonneville last year with a 650cc Triumph twin, I had a chat with a chap from the Triumph factory and in the course of this conversation mentioned that we were using 8000 rpm as a rev limit, and considered that quite safe. The gentleman in question was absolutely staggered at this bit of news, and looked at me as though I were quite mad when he was told that the engine was producing maximum power at 7200 rpm. When I inquired about Triumph's work with this same engine, he informed me that Mr. Edward Turner, who heads Triumph, was firmly opposed to any such fiddling about and that the factory engineers were expressly forbidden to do this. He added, however, that they would be pleased to hear the results of our development program.

Needless to say, this is an incredible attitude for a company that has one of the very best motorcycle engines in the world. The parent company owes a great deal to its dealers and distributors in this country, who have a somewhat more enlightened attitude toward racing, and who have given Triumph its excellent reputation here.

With all, I imagine that Paul Dunstall learned a thing or two through his visit to Daytona and this just might have farreaching effects back in England. Indeed, we may even see race-prepared motorcycles being sent across the Atlantic the other way. In any case, Dunstall will have learned not to underestimate the quality of the machinery on this side of the pond. You can bet that the next batch of Dunstall-tuned Nortons sent to Daytona (if indeed there will be any more) will have a lot more engine work incorporated. The 1964 Daytona Nortons had all of the bolton racing hardware, and had braking and handling of the highest order, but in terms of sheer power and/or reliability they were no match for the equipment fielded by the barbarians from the west.