H&C TRIUMPH SPECIAL

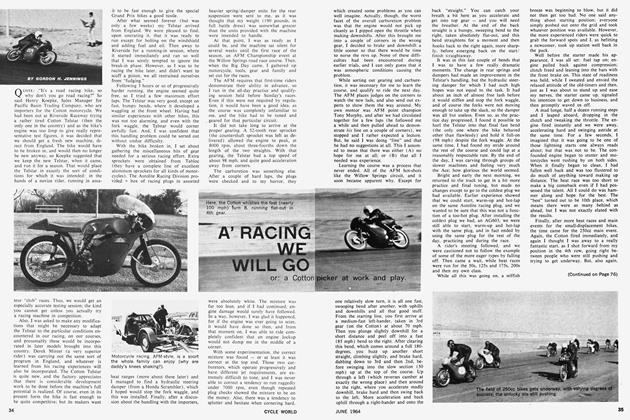

OUTSTANDING performances by Triumph motorcycles in our TT races are nothing new, but recently the crowd at Ascot Park witnessing the 100-lap TT was treated to a performance by one such Triumph that they will never forget. Clark White, riding a 650cc Triumph twin, moved up through the field (which included some exceptionally good bike/rider combinations) to take the lead on the 3rd lap and was never in any danger of losing it from that point to the finish. It was, obviously, a fine exhibition of rider skill, but anyone who saw the race must surely have noticed all the help White was getting from the machine. His Triumph was clearly faster than anything else there, and considering the length of the race, it was clear that the power had not been gained at any cost to reliability. We decided, then and there, to make it our business to find out more about this particular TR-6.

The machine is owned and tuned by Gary Robison, of Harman and Collins Engineering, and he very kindly consented to lay bare its internals for photos, and to tell us all that had gone into the modification and preparation of this Triumph. The modifications are, as you will see, quite extensive, and include not only the engine, but the brakes and the oil tank.

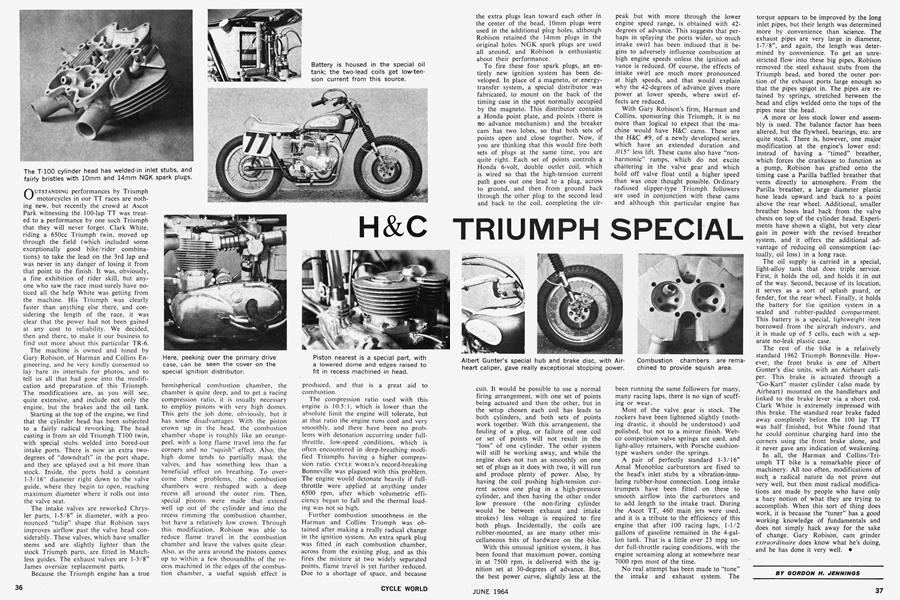

Starting at the top of the engine, we find that the cylinder head has been subjected to a fairly radical reworking. The head casting is from an old Triumph T100 twin, with special stubs welded into bored-out intake ports. There is now an extra twodegrees of "downdraft" in the port shape, and they are splayed out a bit more than stock. Inside, the ports hold a constant 1-3/16" diameter right down to the valve guide, where they begin to open, reaching maximum diameter where it rolls out into the valve seat.

The intake valves are reworked Chrysler parts, 1-5/8" in diameter, with a pronounced "tulip" shape that Robison says improves airflow past the valve head considerably. These valves, which have smaller stems and are slightly lighter than the stock Triumph parts, are fitted in Matchless guides. The exhaust valves are 1-3/8" James oversize replacement parts.

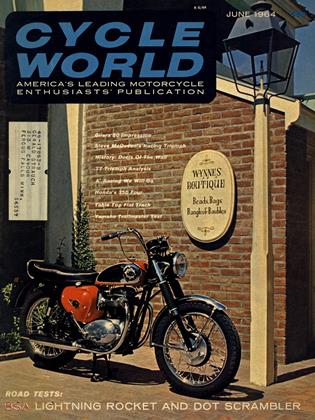

Because the. Triumph engine has a true hemispherical combustion chamber, the chamber is quite deep, and to get a racing compression ratio, it is usually necessary to employ pistons with very high domes. This gets the job done, obviously, but it has some disadvantages. With the piston crown up in the head, the combustion chamber shape is roughly like an orangepeel, with a long flame travel into the far corners and no "squish" effect. Also, the high dome tends to partially mask the valves, and has something less than a beneficial effect on breathing. To overj come these problems, the combustion chambers were reshaped with a deep recess all around the outer rim. Then, special pistons were made that extend well up out of the cylinder and into the recess rimming the combustion chamber, but have a relatively low crown. Through this modification, Robison was able to reduce flame travel in the combustion chamber and leave the valves quite clear. Also, as the area around the pistons comes up to within a few thousandths of the recess machined in the edges of the combustion chamber, a useful squish effect is produced, and that is a great aid to combustion.

The compression ratio used with this engine is 10.5:1, which is lower than the absolute limit the engine will tolerate, but at that ratio the engine runs cool and very smoothly, and there have been no problems with detonation occurring under fullthrottle, low-speed conditions, which is often encountered in deep-breathing modified Triumphs having a higher compression ratio, CYCLE WORLD'S record-breaking Bonneville was plagued with this problem. The engine would detonate heavily if fullthrottle were applied at anything under 6500 rpm, after which volumetric efficiency began to fall and the thermal loading was not so high.

Further combustion smoothness in the Harman and Collins Triumph was obtained after making a really radical change in the ignition system. An extra spark plug was fitted in each combustion chamber, across from the existing plug, and as this fires the mixture at two widely separated points, flame travel is yet further reduced. Due to a shortage of space, and because the extra plugs lean toward each other in the center of the head, 10mm plugs were used in the additional plug holes, although Robison retained the 14mm plugs in the original holes. NGK spark plugs are used all around, and Robison is enthusiastic about their performance.

To fire these four spark plugs, an entirely new ignition system has been developed. In place of a magneto, or energytransfer system, a special distributor was fabricated, to mount on the back of the timing case in the spot normally occupied by the magneto. This distributor contains a Honda point plate, and points (there is no advance mechanism) and the breaker cam has two lobes, so that both sets of points open and close together. Now, if you are thinking that this would fire both sets of plugs at the same time, you are quite right. Each set of points controls a Honda 6-volt, double outlet coil, which is wired so that the high-tension current path goes out one lead to a plug, across to ground, and then from ground back through the other plug to the second lead and back to the coil, completing the circuit. It would be possible to use a normal firing arrangement, with one set of points being actuated and then the other, but in the setup chosen each coil has leads to both cylinders, and both sets of points work together. With this arrangement, the fouling of a plug, or failure of one coil or set of points will not result in the "loss" of one cylinder. The other system will still be working away, and while the engine does not run as smoothly on one set of plugs as it does with two, it will run and produce plenty of power. Also, by having the coil pushing high-tension current across one plug in a high-pressure cylinder, and then having the other under low pressure (the non-firing cylinder would be between exhaust and intake strokes) less voltage is required to fire both plugs. Incidentally, the coils are rubber-mounted, as are many other miscellaneous bits of hardware on the bike.

With this unusual ignition system, it has been found that maximum power, coming in at 7500 rpm, is delivered with the ignition set at 30-degrees of advance. But, the best power curve, slightly less at the peak but with more through the lower engine speed range, is obtained with 42degrees of advance. This suggests that perhaps in splaying the ports wider, so much intake swirl has been induced that it begins to adversely influence combustion at high engine speeds unless the ignition advance is reduced. Of course, the effects of intake swirl are much more pronounced at high speeds, and that would explain why the 42-degrees of advance gives more power at lower speeds, where swirl effects are reduced.

With Gary Robison's firm, Harman and Collins, sponsoring this Triumph, it is no more than logical to expect that the machine would have H&C cams. These are the H&C #9, of a newly developed series, which have an extended duration and .015" less lift. These cams also have "nonharmonic" ramps, which do not excite chattering in the valve gear and which hold off valve float until a higher speed than was once thought possible. Ordinary radiused slipper-type Triumph followers are used in conjunction with these cams and although this particular engine has been running the same followers for many, many racing laps, there is no sign of scuffing or wear.

Most of the valve gear is stock. The rockers have been lightened slightly (nothing drastic, it should be understood) and polished, but not to a mirror finish. Webco competition valve springs are u$ed, and light-alloy retainers, with Porsche cushiontype washers under the springs.

A pair of perfectly standard 1-3/16" Amal Monobloc carburetors are fixed to the head's inlet stubs by a vibration-insulating rubber-hose connection. Long intake trumpets have been fitted on these to smooth airflow into the carburetors and to add length to the intake tract. During the Ascot TT, 460 main jets were used, and it is a tribute to the efficiency of this engine that after 100 racing laps, 1-1/2 gallons of gasoline remained in the 4-gallon tank. That is a little over 23 mpg under full-throttle racing conditions, with the engine screaming along at somewhere near 7000 rpm most of the time.

No real attempt has been made to "tune" the intake and exhaust system. The torque appears to be improved by the long inlet pipes, but their length was determined more by convenience than science. The exhaust pipes are very large in diameter, 1-7/8", and again, the length was determined by convenience. To get an unrestricted flow into these big pipes, Robison removed the steel exhaust stubs from the Triumph head, and bored the outer portion of the exhaust ports large enough so that the pipes spigot in. The pipes are retained by springs, stretched between the head and clips welded onto the tops of the pipes near the head.

A more or less stock lower end assembly is used. The balance factor has been altered, but the flywheel, bearings, etc. are quite stock. There is, however, one major modification at the engine's lower end: instead of having a "timed" breather, which forces the crankcase to function as a pump, Robison has grafted onto the timing case a Parilla baffled breather that vents directly to atmosphere. From the Parilla breather, a large1 diameter plastic hose leads upward and back to a point above the rear wheel. Additional, smaller breather hoses lead back from the valve chests on top of the cylinder head. Experiments have shown a slight, but very clear gain in power with the revised breather system, and it offers the additional advantage of reducing oil consumption (actually, oil loss) in a long race.

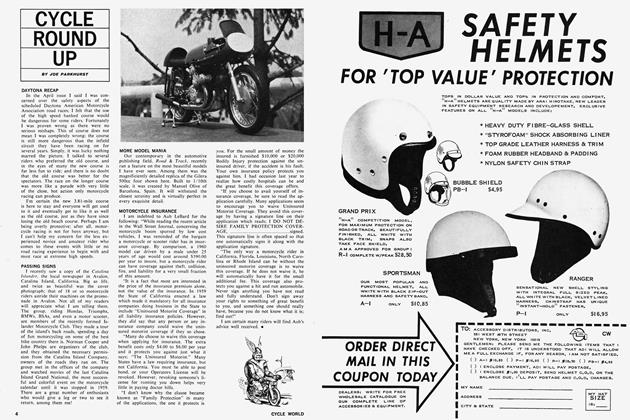

The oil supply is carried in a special, light-alloy tank that does triple service. First, it holds the oil, and holds it in out of the way. Second, because of its location, it serves as a sort of splash guard, or fender, for the rear wheel. Finally, it holds the battery for the ignition system in a sealed and rubber-padded compartment. This battery is a special, lightweight item borrowed from the aircraft industry, and it is made up of 5 cells, each with a separate no-leak plastic case.

The rest of the bike is a relatively standard 1962 Triumph Bonneville. However, the front brake is one of Albert Gunter's disc units, with an Airheart caliper. This brake is actuated through a "Go-Kart" master cylinder (also made by Airheart) mounted on the handlebars and linked to the brake lever via a short rod. Clark White is extremely impressed with this brake. The-standard rear brake faded away completely before the 100 lap TT was half finished, but White found that he could continue charging hard into the corners using the front brake alone, and it. never gave any indication of weakening.

In all, the Harman and Collins/Triumph TT bike is a remarkable piece of machinery. All too often, modifications of such a radical nature do not prove out very well, but then most radical modifications are made by people who have only a hazy notion of what they are trying to accomplish. When this sort of thing does work, it is because the "tuner" has a good working knowledge of fundamentals and does not simply hack away for the sake of change. Gary Robison, cam grinder extraordinaire does know what he's doing, and he has done it very well. •

GORDON H. JENNINGS