A' RACING WE WILL GO

or: a Cotton picker at work and play.

GORDON H. JENNINGS

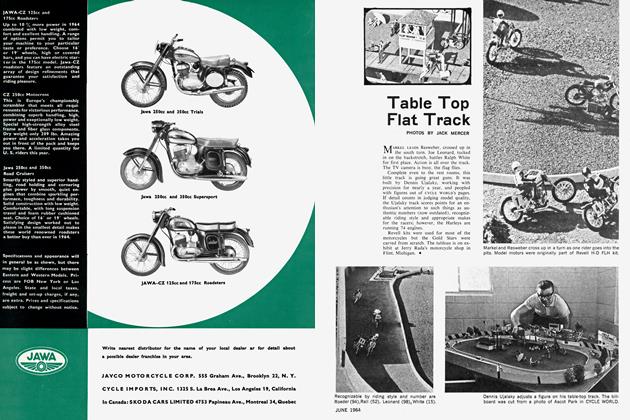

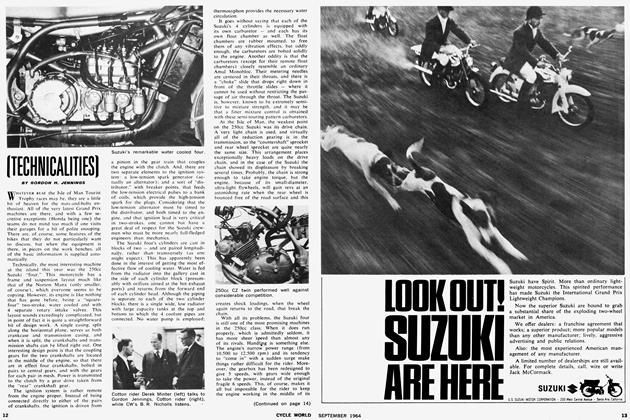

QUOTE: "It's a road racing bike, so why don't you go road racing?" So said Henry Koepke, Sales Manager for Pacific Basin Trading Company, who are importers for the Cotton motorcycle. We had been out at Riverside Raceway trying a rather tired Cotton Telstar (then the only one in the country) and as the bike's engine was too limp to give really representative test figures, it was decided that we should get a fresh new machine, direct from England. The bike would have to be broken in, and would then no longer be new anyway, so Koepke suggested that we keep the new Telstar, when it came, and run it for a season. That would place the Telstar in exactly the sort of conditions for which it was intended: in the hands of a novice rider, running in amateur "club" races. Thus, we would get an especially accurate testing session; the kind you cannot get unless you actually try a racing machine in competition.

Also, I was asked to make any modifications that might be necessary to adapt the Telstar to the particular conditions encountered in our racing, on our courses, and presumably these would be incorporated in later models brought into this country. Derek Minter (a very superior rider) was carrying out the same sort of program in England, and whatever is learned from his racing experiences will also be incorporated. The Cotton Telstar is quite new, and the factory appreciates that there is considerable development work to be done before the machine's full potential is realized. Of course, even in its present form the bike is fast enough to be quite competitive; but its makers want it to be fast enough to give the special Grand Prix bikes a good tussle.

After what seemed forever (but was only a few weeks) my Telstar arrived from England. We were pleased to find, upon uncrating it, that it was ready to run except for bolting on the windshield and adding fuel and oil. Then away to Riverside for a running-in session, where it started immediately and ran so well that I was sorely tempted to ignore the break-in phase. However, as I was to be racing the bike later, and didn't want to scuff a piston, we all restrained ourselves from "fudging."

Following 3 hours or so of progressively harder running, the engine seemed quite free, so I tried a few maximum effort laps. The Telstar was very good, except on fast, bumpy bends, where it developed a waggling at the front wheel. Having had similar experiences with other bikes, this was not too alarming, and even with the fork waggle, the Txelstar would corner awfully fast. And, I was confident that this handling problem could be sorted out without undue difficulty.

With the bike broken in, I set about gathering the miscellaneous bits of gear needed for a serious racing effort. Extra sprockets were obtained from Tabloc (they have a complete line of excellent aluminum sprockets for all kinds of motorcycles). The Autolite Racing Division provided ? box of racing plugs in assorted heat ranges (more about these later) and I managed to find a hydraulic steering damper (from a Honda Scrambler), which I hoped would stop the fork waggle, and this was installed. Finally, after a discussion about the handling with the importers, heavier spring/damper units for the rear suspension were sent to me, as it was thought that my weight (190 pounds, in full battle dress) was somewhat greater than the units provided with the machine were intended to handle.

At that point, I was as ready as I could be, and the machine sat silent for several weeks until the first race of the season, an AFM Championship event at the Willow Springs road race course. Then, when the Big Day came, I gathered up motorcycle, tools, gear and family and set out for the races.

The AFM requires that first-time riders demonstrate their ability in advance, so I ran in the all-day practice and qualifying session held before Sunday's races. Even if this were not required by regulation, it would have been a good idea, as the course was completely unfamiliar to me, and the bike had to be tuned and geared for that particular circuit.

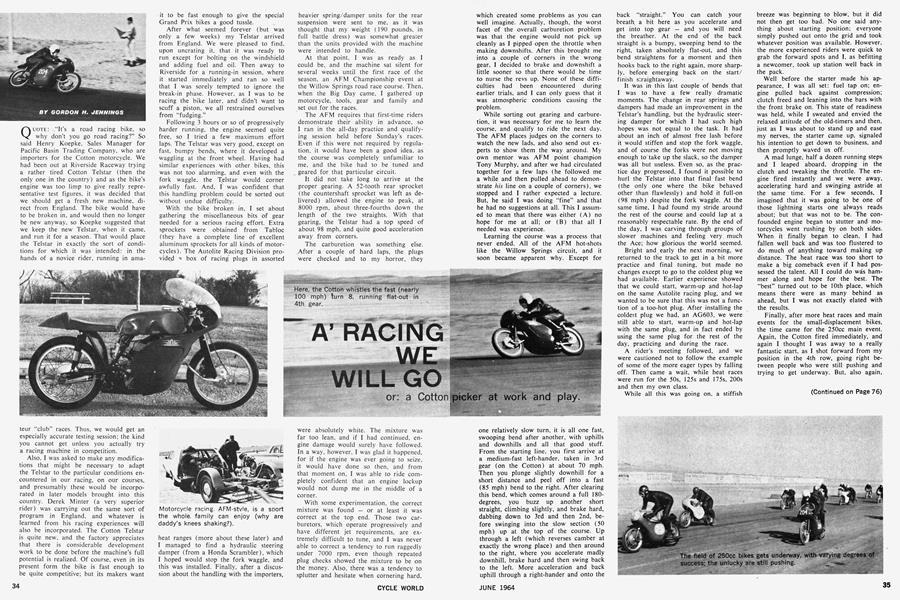

It did not take long to arrive at the proper gearing. A 52-tooth rear sprocket (the countershaft sprocket was left as delivered) allowed the engine to peak, at 8000 rpm, about three-fourths down the length of the two straights. With that gearing, the Telstar had a top speed of about 98 mph, and quite good acceleration away from corners.

The carburetion was something else. .After a couple of hard laps, the plugs were checked and to my horror, they were absolutely white. The mixture was far too lean, and if I had continued, engine damage would surely have followed. In a way, however, I was glad it happened, for if the engine was ever going to seize, it would have done so then, and from that moment on, I was able to ride completely confident that an engine lockup would not dump me in the middle of a corner.

With some experimentation, the correct mixture was found - or at least it was correct at the top end. Those two carburetors, which operate progressively and have different jet requirements, are extremely difficult to tune, and I was never able to correct a tendency to run raggedly under 7000 rpm, even though repeated plug checks showed the mixture to be on the money. Also, there was a tendency to splutter and hesitate when cornering hard. which created some problems as you can well imagine. Actually, though, the worst facet of the overall carburetion problem was that the engine would not pick up cleanly as I pipped open the throttle when making downshifts. After this brought me into a couple of corners in the wrong gear, I decided to brake and downshift a little sooner so that there would be time to nurse the revs up. None of these difficulties had been encountered during earlier trials, and I can only guess that it was atmospheric conditions causing the problem.

While sorting out gearing and carburetion, it was necessary for me to learn the course, and qualify to ride the next day. The AFM places judges on the corners to watch the new lads, and also send out experts to show them the way around. My own mentor was AFM point champion Tony Murphy, and after we had circulated together for a few laps (he followed me a while and then pulled ahead to demonstrate his line on a couple of corners), we stopped and I rather expected a lecture. But, he said I was doing "fine" and that he had no suggestions at all. This I assumed to mean that there was either (A) no hope for me at all; or (B) that all I needed was experience.

Learning the course was a process that never ended. All of the AFM hot-shots like the Willow Springs circuit, and it soon became apparent why. Except for one relatively slow turn, it is all one fast, swooping bend after another, with uphills and downhills and all that good stuff. From the starting line, you first arrive at a medium-fast left-hander, taken in 3rd gear (on the Cotton) at about 70 mph. Then you plunge slightly downhill for a short distance and peel off into a fast (85 mph) bend to the right. After clearing this bend, which comes around a full 180degrees, you buzz up another short straight, climbing slightly, and brake hard, dabbing down to 3rd and then 2nd, before swinging into the slow section (50 mph) up at the top of the course. Up through a left (which reverses camber at exactly the wrong place) and then around to the right, where you accelerate madly downhill, brake hard and then swing back to the left. More acceleration and back uphill through a right-hander and onto the back "straight." You can catch your breath a bit here as you accelerate and get into top gear — and you will need the breather. At the end of the back straight is a bumpy, sweeping bend to the right, taken absolutely flat-out, and this bend straightens for a moment and then hooks back to the right again, more sharply, before emerging back on the start/ finish straightaway.

It was in this last couple of bends that I was to have a few really dramatic moments. The change in rear springs and dampers had made an improvement in the Telstar's handling, but the hydraulic steering damper for which I had such high hopes was not equal to the task. It had about an inch of almost free lash before it would stiffen and stop the fork waggle, and of course the forks were not moving enough to take up the slack, so the damper was all but useless. Even so, as the practice day progressed, I found it possible to hurl the Telstar into that final fast bend (the only one where the bike behaved other than flawlessly) and hold it full-on (98 mph) despite the fork waggle. At the same time, I had found my stride around the rest of the course and could lap at a reasonably respectable rate. By the end of the day, I was carving through groups of slower machines and feeling very much the Ace; how glorious the world seemed.

Bright and early the next morning, we returned to the track to get in a bit more practice and final tuning, but made no changes except to go to the coldest plug we had available. Earlier experience showed that we could start, warm-up and hot-lap on the same Autolite racing plug, and we wanted to be sure that this was not a function of a too-hot plug. After installing the coldest plug we had, an AG603, we were still able to start, warm-up and hot-lap with the same plug, and in fact ended by using the same plug for the rest of the day, practicing and during the race.

A rider's meeting followed, and we were cautioned not to follow the example of some of the more eager types by falling off. Then came a wait, while heat races were run for the 50s, 125s and 175s, 200s and then my own class.

While all this was going on, a stiffish breeze was beginning to blow, but it did not then get too bad. No one said anything about starting position; everyone simply pushed out onto the grid and took whatever position was available. However, the more experienced riders were quick to grab the forward spots and I, as befitting a newcomer, took up station well back in the pack.

Well before the starter made his appearance, I was all set: fuel tap on; engine pulled back against compression; clutch freed and leaning into the bars with the front brake on. This state of readiness was held, while I sweated and envied the relaxed attitude of the old-timers and then, just as I was about to stand up and ease my nerves, the starter came up, signaled his intention to get down to business, and then promptly waved us off.

A mad lunge, half a dozen running steps and I leaped aboard, dropping in the clutch and tweaking the throttle. The engine fired instantly and we were away, accelerating hard and swinging astride at the same time. For a few seconds, I imagined that it was going to be one of those lightning starts one always reads about; but that was not to be. The confounded engine began to stutter and motorcycles went rushing by on both sides. When it finally began to clean, I had fallen well back and was too flustered to do much of anything toward making up distance. The heat race was too Short to make a big comeback even if I had possessed the talent. All I could do wás hammer along and hope for the best. The "best" turned out to be 10th place, which means there were as many behind as ahead, but I was not exactly elated with the results.

Finally, after more heat races and main events for the small-displacement bikes, the time came for the 250cc main event. Again, the Cotton fired immediately, and again I thought I was away to a really fantastic start, as I shot forward from my position in the 4th row, going right between people who were still pushing and trying to get underway. But, also again, the engine began to stutter, and neither slipping the clutch nor feathering the throttle was of any avail. People went blasting by, and the Cotton and I found ourselves relegated to about 12th place on the first lap.

(Continued on Page 76)

By this time, that stiffish breeze had turned into a gale-force wind, and imagine my great surprise when I arrived, with the wind at my back, at that very fast final bend with 8400 rpm showing on the tach. That was 102 mph and a bit too fast, but I was trying to retake some of the people who had gotten by at the start, so I peeled off and hoped for the best. There followed a surging and waggling the like of which I had never experienced and hope never to feel again. Far off the correct line, I recovered and squeaked through the hook at the end by luck alone, losing a couple of places on the process. However, there were still those bikes just ahead and it was unthinkable to ease off. Through the back section I gained a few places, and got right up into the middle of the pack. Unfortunately, at that point the pack worked back around to that accursed last turn, and this time everyone was really flying. I have no idea of the tach reading, being busy at that time, but the resulting waggle was worse than before, and the Cotton ran so wide that it was teetering along at the edge of the course. The waggling and the wind just moved it ou,t and there was nothing to be done about it. I should mention that while all this was going on, I passed bikes that were misbehaving much worse than the Cotton, and as the Telstar's handling was excellent on the course's smoother portions, our position was improving somewhat. But, there was nothing I could do on that one bumpy turn except ease back a bit on the entrance and go through slightly slower at full throttle, which seemed to steady the bike. This did not do much for lap times, but the only alternative was very likely a crash at high speed, and that was not a very appealing prospect. As a matter of fact, the chap that was leading the race on a Yamaha TD-1 did crash on that fast bend, and because I arrived on the scene while the dust was still flying and while he was still lying there (stunned but relatively uninjured), my resolve to be calm and not do anything rash was strengthened.

More laps went by, while those ahead pulled farther ahead, and those behind fell farther behind, until to my surprise, the starter waved his flags (blue and then checkered) and the race was over. After all the shuffling around, passing and repassing, I had finished 8th (in a field of about 20), which was a great disappointment to me but a very respectable showing for a new bike and new rider according to the regulars. Still, had I been able to sort out the tuning and handling problems, my finishing position could have been improved by 3 or 4 places, which would have made me much happier.

Probably the most significant thing about the whole adventure was that road racing proved to be every bit as much fun as it appears from the sidelines, and that the AFM is a good group of people; friendly and helpful, and delighted that someone else wants to come out and play. As goes without saying, I will return. The Cotton has the potential, and with practice yours truly should become somewhat faster. The years of test riding were a great advantage, of course, but it is one thing to go fast all by one's self and quite another to do it with somebody's front tire by your elbow. Also, it is necessary to charge a lot harder into corners than is required when test riding, and that is something that takes some practice before it begins to feel natural.

More practice is in the offing for me, and some modifications for the Cotton. The bike's Starmaker engine is stout enough to take a lot more revolutions, so we plan to rework the porting and change the twin Amal Monobloc carburetors for a single 38mm (1.5") TT-pattern Dellorto. Minter's Telstar is similarly equipped (with a 1-1/2" GP Amal) and the word is that this adds a thousand revs and 6 horsepower. We will also be experimenting with exhaust systems to suit the higher power band. There will also be changes in spring and damper units for the suspension, and probably a friction steering damper. The Honda damper is now being reworked to improve its effectiveness in damping small oscillations. Whatever we do that works, or fails, will be reported to Cotton, and to our readers, who may be planning a fling at road racing and might find the information useful.