Where Is World Superbike Going?

Will Dorna impose Superstock rules?

October 1 2017 Kevin CameronWill Dorna impose Superstock rules?

October 1 2017 Kevin CameronRace Watch

TOO QUICK FOR MOTOGP COMFORT COST-CUTTING MEASURES TRIFECTA FOR SUCCESS

THE VIEW FROM INSIDE THE PADDOCK

WHERE IS WORLD SUPERBIKE GOING?

Will Dorna impose Superstock rules?

Kevin Cameron

World Superbike went its own way as a productionbased roadracing series until it came under Dorna management in July 2012. Although the 2013 series went ahead as planned, changes were soon made in technical rules. In a recent interview, Dorna CEO Carmelo Ezpeleta commented, “In the past this was a championship that wanted to compete with MotoGP, but it doesn’t work. You cannot compete with MotoGP.”

Just over two weeks ago, the website GPOne noted that all it takes is a slight upset—rain or tire problems—to bring the lap times of WorldSBK and MotoGP very close together, as they were at Assen. This result is despite four years of rules changes intended to push World Supers closer to stock.

Ezpeleta continued, “We need to go back to the original idea [a production-based series]. The rules need to change for the 2018 season. All the manufacturers agree in the urgency of these changes. They all practically agree to adopt the rules of the Superstock 1000 to Superbike, and we are discussing the introduction of the single ECU as in MotoGP.”

WORLD SUPERBIKE

“Superstock rules? Most national championships are moving that way, mainly for cost. But cost of equipment is only 30 percent of [racing’s] budget—the rest is hiring riders and technicians, travel, et cetera. The positive to a Superstoclc rule is that cost drops. The negative: If you don’t have a solid streetbilce, the racer is not good.”

-Ernesto Marinelli,

Ducati’s Superbike project director

Have a look at Superstock tech rules on the FIM’s site; above the crankcase the only things that may be changed are the head gasket and spark plugs. Chassis, swingarm, and fork are stock, with price-limited internals and a rear unit permitted. Only the original ECU or a price-capped kit ECU are permitted.

This is appealing for two reasons. First, modern sportbikes have become raceable in stock form and, second, in a weak economy, racing must seek the most affordable path.

When we asked Ducati’s Superbike Project Director Ernesto Marinelli about this, he said, “Superstock rules? Most national championships are moving that way, mainly for cost. But cost of equipment is only 30 percent of [racing’s] budget—the rest is hiring riders and technicians, travel, et cetera. The positive to a Superstock rule is that cost drops. The negative: If you don’t have a solid streetbilce, the racer is not good.”

In the past, that has been the reason to permit certain modifications, to allow a manufacturer with an older model to remain competitive by raising compression, relocating a swingarm pivot, or adapting steering geometry to evolving tires.

As for adopting a single ECU, Marinelli noted it has worked in MotoGP. But if that stops a manufacturer from using racing for software R&D, that cost must be borne by another department.

We learned how rules changes have affected Kawasaki factory rider Tom Sykes from his crew chief, Marcel Duinker: “In 2013, Kawasaki won the title after 20 years [last time was Scott Russell in 1993]. A little bit strange if after 20 years you win one year, why should [Dorna] begin to change the rules against one manufacturer?”

He went on to point out that for small European manufacturers it is usual to “make a special version”—a homologation special with the necessary racing parts as “stock”—while for Japanese makers this is more difficult as they tool for a larger market at lower unit prices. During the Ducati Panigale’s 2015 model change it was given such things as titanium valves and connecting rods and a lighter crankshaft.

In practical terms, the recent reversion to such things as stock pistons, valves, and crank (weight) has reduced the Kawasaki’s acceleration such that Sykes can no longer use his own riding style. He has been successful as an extreme stop-andgo rider, braking late and hard, getting turned early at lower apex speed, and then using the engine’s acceleration to recover competitive exit speed. Sykes is currently retraining himself to ride a more flowing line, losing less speed at the apex so he can lap competitively even with his acceleration cut by new rules.

UNCERTAIN FUTURE: At present Kawasaki and Ducati are the only fully invested factory efforts in WSBK. Will a move toward Superstock rules attract more manufacturer involvement or escalate into a production bike arms race that sees the cost put on the consumer?

BY THE NUMBERS

BO Percent of WorldSBK’s racing budget that is equipment

20 Years between Kawasaki taking the WorldSBK title, first with Scott Russell in 1993 then with Tom Sykes in 2013

0 Podiums for Ducati’s Panigale in 2013 or 2014, despite its introduction in late 2011

Aprilia and Sylvain Guintoli won the championship in 2014, but Ducati, struggling to make its “Panigale” (introduced in November 2011) competitive, achieved no podiums in 2013 or 2014. At present, there are Hondas and Yamahas in WorldSBK, but they have little if any factory backing. As Aprilia is at present, they are spending their racing budgets in MotoGP.

When we spoke with current series champion and point leader Johnny Rea, he pointed out that at present the best riders are on the best bikes and asked, “Do we penalize them [Kawasaki and Ducati] for taking the championship seriously, by making [the equipment rules] more basic?”

In his view, adoption of Superstock rules would only “make certain manufacturers stand out even more. I think Dorna should find a way to convince the manufacturers to spend some money,” he added.

Ronald Ten Kate’s organization has been developing the Honda for many years. He noted, “The old bike, we knew all about it. The new bike came late and with it we are not at that stage.” He observed that the two top teams “...are a step ahead of anybody else. In middle season we were getting somewhere, but then we lost Nicky.”

Ten Kate stated that, “[HRC is] not feeding parts into the team. That’s not new; in last year’s bike there were no HRC parts or electronics.” They had to develop their own throttleby-wire system, but as soon as it was working rules changes were announced so “...we knew we couldn’t have that system.”

All seem to agree that the top teams have three important advantages:

1) They can attract and employ the top riders (worth roughly a second a lap).

2) They have experienced personnel in management and technical positions (worth a chunk of another second).

3) They know their equipment well because they have been in the series for years.

I saw the results at Laguna Seca—fourth place (Marco Melandri) was 15 seconds back (0.6 second a lap) and 15th place was 51 seconds out, or just over two seconds a lap. In MotoGP the grid is now fully engineered bikes—factory entries or oneto two-year-old factory bikes in satellite teams. Plenty of hot talent (like Johann Zarco or Jonas Folger) is available from Moto2. But WorldSBK is four top factory bikes (Kawasaki and Ducati) plus two half-funded Aprilias, with the rest being non-factory teams that hope for factory help. Riders come to World Supers either from MotoGP or from national Superbike series.

Dorna seems sure that Superstock 1000 rules can overcome one, two, and three above. Or, wait! Is its idea something else entirely? What if the program is to force factories out of Superbike altogether, pushing what factory support it had into MotoGP? In that case, the future of production-based racing would be the several Superstock national series, feeding riders into a World Superstock championship. That plan would be RIP Superbike, as exotic and highly modified production bikes would be seen no more. This brings us to the final possible motivation for clipping the wings of World Superbike: to make sure that its lap times never again come embarrassingly close to those of MotoGP.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

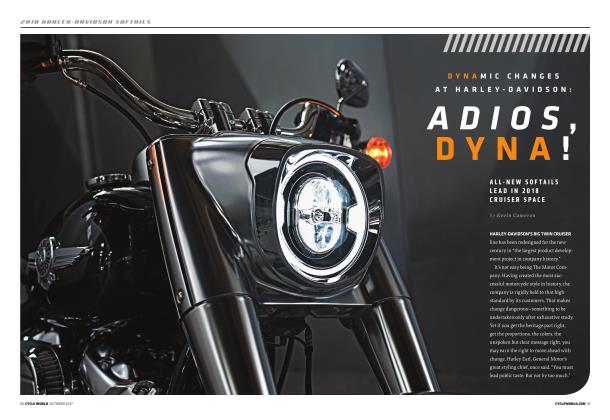

2018 Harley-Davidson Softails

2018 Harley-Davidson SoftailsDynamic Changes At Harley-Davidson: Adios, Dyna!

OCTOBER 2017 By Kevin Cameron -

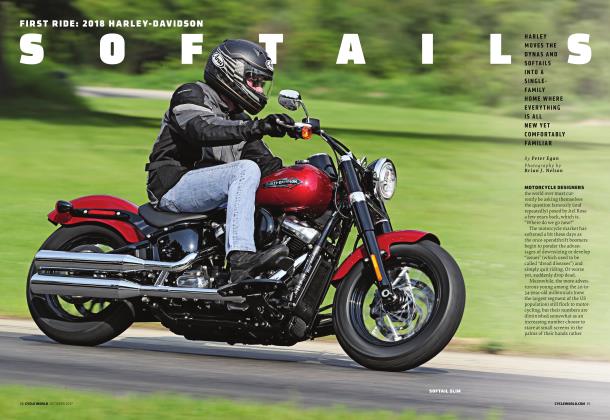

First Ride: 2018 Harley-Davidson Softails

OCTOBER 2017 By Peter Egan -

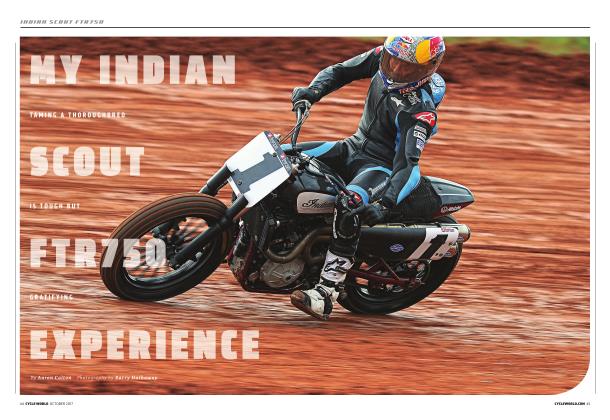

My Indian Scout Ftr 750 Experience

OCTOBER 2017 By Aaron Colton -

Service

OCTOBER 2017 By Ray Nierlich -

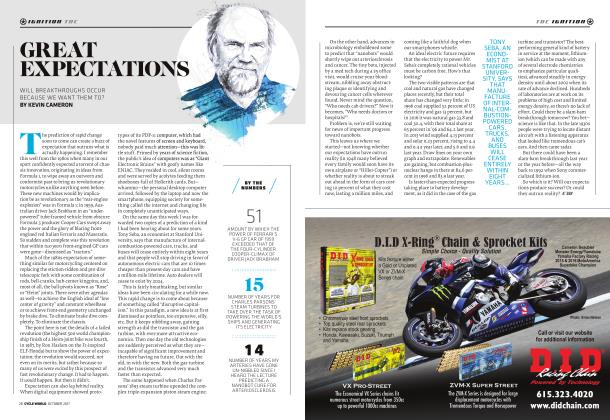

Ignition

IgnitionGreat Expectations

OCTOBER 2017 By Kevin Cameron -

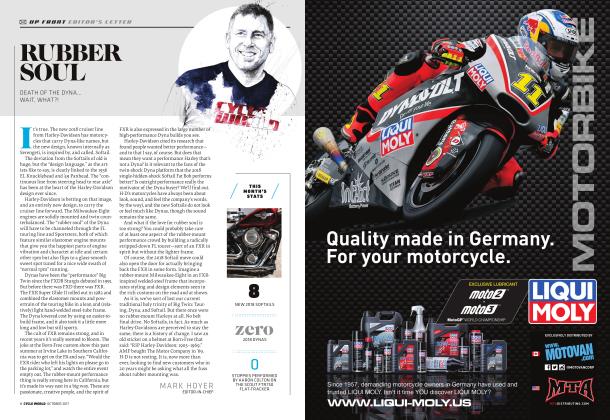

Up Front

Up FrontRubber Soul

OCTOBER 2017 By Mark Hoyer