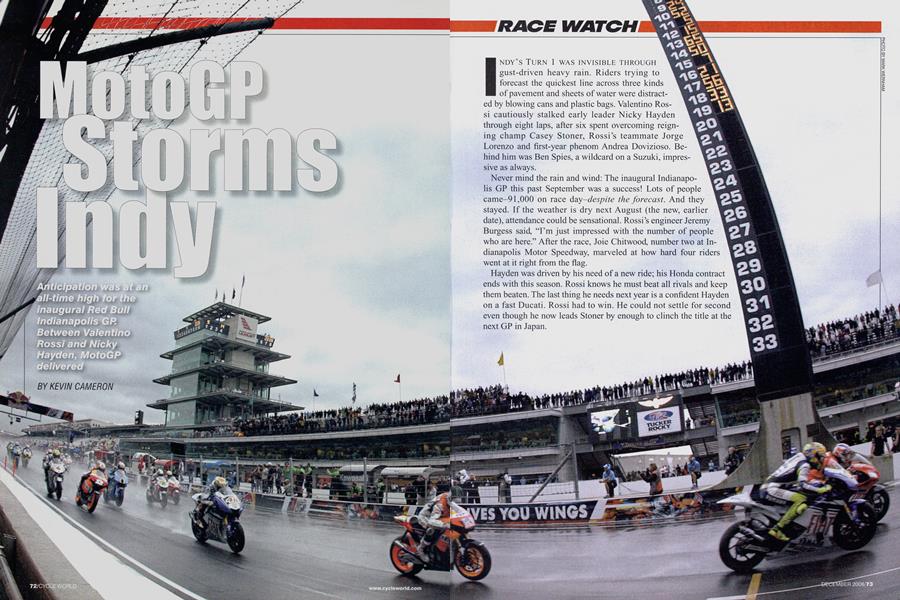

MotoGP Storms Indy

Anticipation was at an all-time high for the inaugural Red Bull Indianapolis GP. Between Valentino Rossi and Nicky Hayden, MotoGP delivered

KEVIN CAMERON

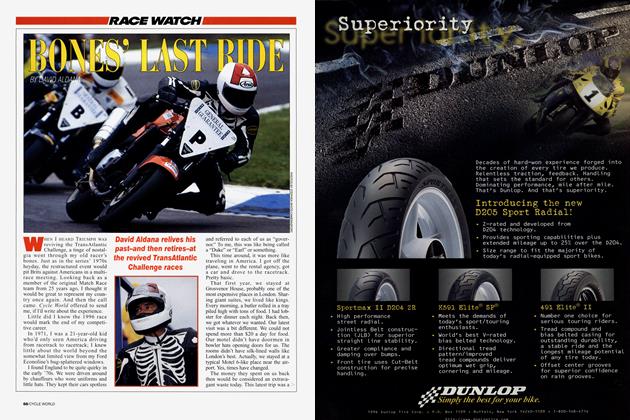

RACE WATCH

INDY’S TURN 1 WAS INVISIBLE THROUGH gust-driven heavy rain. Riders trying to forecast the quickest line across three kinds of pavement and sheets of water were distracted by blowing cans and plastic bags. Valentino Rossi cautiously stalked early leader Nicky Hayden through eight laps, after six spent overcoming reigning champ Casey Stoner, Rossi’s teammate Jorge Lorenzo and first-year phenom Andrea Dovizioso. Behind him was Ben Spies, a wildcard on a Suzuki, impressive as always.

Never mind the rain and wind: The inaugural Indianapolis GP this past September was a success! Lots of people came-91,000 on race day-despite the forecast. And they stayed. If the weather is dry next August (the new, earlier date), attendance could be sensational. Rossi’s engineer Jeremy Burgess said, “I’m just impressed with the number of people who are here.” After the race, Joie Chitwood, number two at Indianapolis Motor Speedway, marveled at how hard four riders went at it right from the flag.

Hayden was driven by his need of a new ride; his Honda contract ends with this season. Rossi knows he must beat all rivals and keep them beaten. The last thing he needs next year is a confident Hayden on a fast Ducati. Rossi had to win. He could not settle for second even though he now leads Stoner by enough to clinch the title at the next GP in Japan.

On they went, saving slides and dodging cans, but the issue was decided elsewhere. Hayden had switched to a softer Michelin rain tire after the sighting lap, and in the less-wet early going it had heated up and worn away. Now it began to let go in warning slides. Harder rain late in the race was more than the worndown drainage grooves in his tire could handle. Rossi carefully made his way past, into the lead. Then the event was called at three-quarter distance, as the rules require in appalling conditions. Gusts to 75 mph were recorded at the nearby airport, and Hayden described one that “blew me out into the deep stuff!” On Saturday, he'd said, “Rain can be fun. But not ridin' in a monsoon. That kinda takes the fun out of it.”

Tech 3 Yamaha rider Colin Edwards explained the three pavements: IndyCar oval, infield Formula One surface and the newly laid asphalt from Turns 1 to 6. The F-l surface, being older, has an open texture and drains well. The no-camber new asphalt was too flat to drain and held puddles. Edwards’ solution? “You dodge ’em.” But as it rains more, the puddles expand and there’s no place to go. Now, the choice is between slowing down or hydroplaning. Speaking on rainy Friday, Edwards said, “Today was zero excuse to push. No one’s unzippin’ today.”

The Indianapolis facility is huge, like a major air terminal, made of glass, concrete and steel, with more than 250,000 permanent seats. Despite the first-time status of this event, everything went smoothly. There was parking and access. Participants were impressed. The track ran counter-clockwise, using the start-finish straight of the “500” oval, turning left into several infield corners that connected by a short infield straight to a second set of turns that rejoined the main straight.

What about Stoner, whose 2007 dominance on a Ducati was so persuasive? For now, he looks demoralized. In his press conference, he looked down at the table and spoke in an undertone. His injured left hand rested on his leg, and the other flapped as he spoke. In the rainy Friday practices, he let himself be drawn by Kawasaki rainmaster Anthony West (after topping Friday’s two wet practices, West qualified 19th—last—in the dry on Saturday). They traded the top position until Stoner lost grip while accelerating, flying over his bike to land on his face and hands. Meanwhile, Rossi was safely nowhere in the top 10. Racing in the rain requires knowing, not guessing, your limits. In 2002, we saw Rossi, leading a rainy Brazilian GP, let Carlos Checa pass and pull ahead. Why? Because Rossi had decided he was going as fast as he should. Shortly, Checa tipped over.

The rain dampened the intense Bridgestone-vs.-Michelin tire war, and it was clear that on this day both makes had outstanding grip that permitted remarkably high angles of lean. So they should; they are the world’s two largest tire-makers. Repsol Honda’s Dani Pedrosa (who would race to eighth, struggling to adapt to the new tires) made a shock switch to Bridgestones for this race, leaving only six riders still on Michelins.

How could this happen, after Honda’s long, highly successful partnership with Michelin? Take Honda’s perspective: Pedrosa was expected to win the title in 2007, but the unforeseen Stoner/Ducati combo nixed that. As planned, Pedrosa led the early ’08 title chase on Michelins, but then Michelin over-forecast the temperature at Laguna, then had a crippling front tire problem at Brno in the Czech Republic. In recent GPs, Michelins have been sparse in the top 10. This has sparked new talk about a possible spec-tire rule in MotoGP.

To learn more, we interviewed JeanPhilippe Weber, Michelin’s manager for motorcycle racing tires. His view is that Michelin is now on the right track with Lorenzo’s close second place behind Rossi at Misano in Italy. “We know we are competitive,” he said, “but we must solve Laguna and Brno.”

Why did Edwards and Lorenzo, both Yamaha-mounted and riding on Michelins, have such different results ( 10th and second) at Misano? Use of tires is more complex today. Edwards said, “Two corners and I knew I was in trouble,” but the tire’s low initial grip may have resulted from having been scrubbed in during morning warm-up rather than taking it to the grid brand-new.

“I was worried about the warm-up of the tire,” he added. “We came up with a plan to scrub the tire in the morning-at least get the shine off of it. But, in reality, that first part of the tire is pretty grippy. After two laps, it’s gone. So I started the race on a rock-hard tire.”

This makes it appear there is a technology that somehow boosting grip in the opening laps causes the tire to ramp up in temperature faster than it normally would. This would explain how Edwards could lose positions in the opening laps at Misano but then speed up as the tire eventually reached its intended operating temperature. Don’t tire warmers take

care of all that? Although different manufacturers call for different temperatures in the warmers, it appears that keeping tires too hot for any length of time damages their grip. Tire warmers help but can’t do the whole job.

Weber summed up Michelin’s current position by saying that it must optimize the way it uses its technology and “focus on what the rider wants and needs.” Design of front tires is complex, he said, because it must provide the rider with the desired feel, give confidence and be progressive.

For Pedrosa, each race he does not win brings him closer to the possible status of a Randy Mamola, who was second in the 500cc world championship four times. For Honda, with huge investment but no top-class titles since Hayden’s 2006 win, it is imperative to return to competitiveness asap.

At Laguna, Stoner dominated every practice and had such speed that Rossi’s only hope was to get in front and keep him from running away. But at Indianapolis, Rossi was top man, taking pole, setting fastest lap and winning the event. What has changed? A conversation with Burgess revealed that Ducati last year made a big step with control insights provided by Ferrari F-1, but now Yamaha has caught up. At Laguna, Burgess spoke of needing better control to permit earlier acceleration and now Rossi appears to have it.

One element that has changed is Yamaha’s adoption of what it calls “ww-learning.” A year ago, most teams assigned anti-spin and anti-wheelie settings to track segments, with the rider making every setting. By Laguna this year, Rossi spoke of “corner-by-corner” settings, and I wondered at the sheer number of new rider tasks such systems required. Mu is the Greek letter used by engineers to represent the coefficient of friction, in this case, between the rear tire and the track. Many industrial and other control systems now employ automated learning, so why not use the motorcycle itself, working with GPS, to map the accumulating anti-spin history onto a track map? That would provide accurate data in place of rider estimates and, being automatic, it would reduce the rider’s workload in practice.

Exactly this kind of thing has evolved in the automated data-gathering used in test-flying. Every possible means is used to reduce test-pilot workload and shorten the total flight time required. In the 1980s, Erv Kanemoto introduced rational test sequencing as a means of better exploiting limited GP practice time, and Burgess and others have elaborated the concept since then. ATw-learning is simply the extension of this by electronic means.

"The amount of time Valentino spends with me on the general behavior of the motorcycle is significantly smaller than the time he spends breaking down trac tion control, wheelie control and mu learning," Burgess observed.

Indianapolis showed us that despite software and electronics, sudden unpredicted tire spin and hectic slides can still occur, and still require the highest rider skills for recovery. Burgess commented that, “We haven’t had this sort of wheelspin on any track for a very long time.” No currently imaginable electronic system could do what riders had to do: notice that a change in the wind had pushed deeper water onto the racing line. Yet even with rain and wind, the race was not a succession of crashes.

A sub-plot in racing, taking place away from the track in quiet computer rooms, is the “battle of the dynamic models.” A dynamic model for the motorcycle is like the “physics engine” of CG or a video game, which realistically predicts the motions of physical objects, such as the fragments of the exploding Death Star. Useful car dynamic models have existed for at least 35 years, and those for aircraft longer still, but the extra degree of freedom and especially the complex tire grip of motorcycles have resisted analysis. Several years ago, 1 learned that Ducati had set itself the task of creating a refined model that would permit detailed handling analysis. Dynamic modeling has become essential to product design; Harley-Davidson has employed dynamics specialists. Yamaha, in trying to close the “Ducati gap,” has elevated the sophistication of its model. Burgess indicated one of his colleagues and said, “Andrea here is responsible, more than any other per son, for closing the gap."

Sometimes the sheer detail of current knowledge seems too much. Isn't a ma jor appeal of the motorcycle its simplic ity? Nothing, closely examined, is sim ple! Google "rubber compounds' for ex ample. Shortly, I learn that Bridgestone attaches "functional groups" to the ends of long-chain polybutadiene rubber poly mers, which are thereby enabled to bond themselves with special strength to sili ca particles (both Bridgestone and Mi chelin are known to use silica in tire tread compounds). Could this add up to a bet ter combination of compound softness (grip) and tensile strength (wear resis tance)? If every such area is not studied down to its fundamentals, there are holes in your knowledge through which truck loads of problems will roar. Ignorance may have been bliss back in 1935, but today it’s just plain irresponsibility! And so, every maker has a dynamic model, and works to refine and expand it. Racing leads the way.

It was a pleasure to meet Jorge Lorenzo, the Yamaha rider who came up from 250s this season, straight to three podiums and a win in Portugal, then through some heavy crashes, and now back to top finishes. I asked how it was possible to succeed so quickly when so many riders have taken one to three years to achieve podiums.

“If you believe that you will fail,” he replied, “you can find 100 reasons.”

He went on to say that confidence is the most important ingredient, even more so than talent. Yes, he had to learn the electronic systems quickly, and no, the 250s did not prepare him for this new aspect of racing. After the race, it was pointed out that this was the first rain podium of his career. He responded by saying that before the race he felt safe and warm in his motorhome, but once the racing started he was all right and was happy to find that he could do it.

I was pleased to see both the 125 and 250cc GP classes at Indianapolis (although the 250s did not run on Sunday owing to the rain call). Their sharp sounds and smells are long familiar to me, and they function as essential steps upward for aspiring riders. But the managers of GP racing continue to call for team and manufacturer comments on a possible replacement for the 250 class. They propose some kind of 600cc four-stroke, but no one has come forward to support this.

What would it be? A spec engine, same for all teams, in prototype chassis? Production-based 600s in prototype chassis? An all-out 600cc GP formula, costing as much as current MotoGP (imagine 73 x 35mm engines turning 20,000 rpm)? Objections to the above are, respectively, that it 1 ) cannot be a manufacturer’s championship; 2) overlaps World Supersport; and 3) is too expensive for makers now in 250 and possibly even for Japanese budgets. All would eliminate European makes. Veteran two-stroke engineer Harald Bartol, now associated with KTM, believes the proposal is purely political, possibly aimed at forcing KTM or Aprilia to produce an 800cc MotoGP bike. Could this be a case for The Shadow, who alone knows what lurks in the minds of men?

Saturday night it seemed the whole MotoGP paddock had gone to the dirttrack at the Indiana State Fairgrounds, which was packed. All marveled at the courage of riders who think nothing of “runnin’ ’er off into the corner” at 130 mph, just a few feet from walls only cosmetically protected by hay bales. This is racing as it bubbles up from its sources: men and women (yes, women with real talent, whose elbows are as sharp as any man’s) who want to race even though they lack multiple large transporters, people whose “hospitality suite” is the track concession, people whose income is day jobs, not professionally negotiated manufacturer contracts. How do they do it? They do it as they always have-somehow.

MotoGP has recently provided intense action and stunning reversals of fortune for rivals Casey Stoner and Valentino Rossi. When Stoner fell at Laguna, we knew he was mortal. When he fell while leading at both Brno and Misano, we knew that Rossi had zapped him with the confidence-eating virus that defeated Max Biaggi and Sete Gibemau previously. It takes a toll on a rider to know that a stalker is closing and that sudden combat is next. Yet Rossi’s chilling effect upon his rivals is just the tip of an iceberg of other effort. The riding has been brilliant, but the unseen battles below have been essential to it. Surely foremost is the tire war, in which polymer chemists tackle abstruse subjects like compound fatigue and sulfur rebridging. Engine power has see-sawed as the manufacturers tackle and then master pneumatic valve technology (the Hondas finally seem to have the power they need, and Yamaha has taken a step up, as well). Also vast is the new subject of making motorcycles more easily and reliably controllable by electronic means and through predictive understandings of their motions by dynamic modeling.

Fortunately, it is possible to get some idea of the many dimensions of this sport, to perceive it as a giant puzzle and to be able to follow some of the play. I walked around Indy intoxicated by the mysteries, the clues, the conversations. The pattern that emerges is the shape of future motorcycles. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

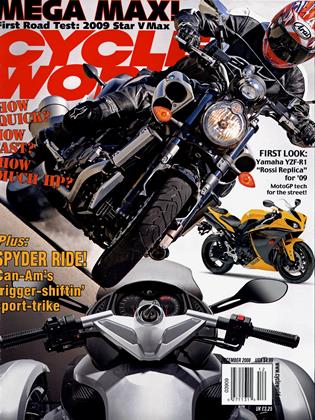

ColumnsUp Front

December 2008 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsThe Great Wisconsin Fly-Over Tour

December 2008 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCHead Banging

December 2008 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

December 2008 -

Roundup

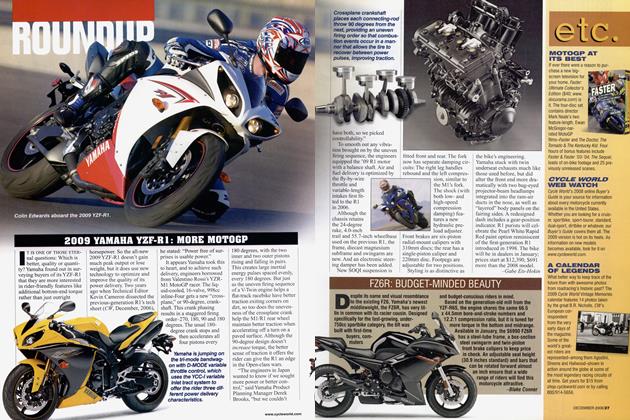

Roundup2009 Yamaha Yzf-R1: More Motogp

December 2008 By Gabe Ets-Hokin -

Roundup

RoundupFz6r: Budget-Minded Beauty

December 2008 By Blake Conner