Great Expectations

WILL BREAKTHROUGHS OCCUR BECAUSE WE WANT THEM TO?

October 1 2017 Kevin CameronWILL BREAKTHROUGHS OCCUR BECAUSE WE WANT THEM TO?

October 1 2017 Kevin CameronGREAT EXPECTATIONS

IGNITION

TDC

WILL BREAKTHROUGHS OCCUR BECAUSE WE WANT THEM TO?

KEVIN CAMERON

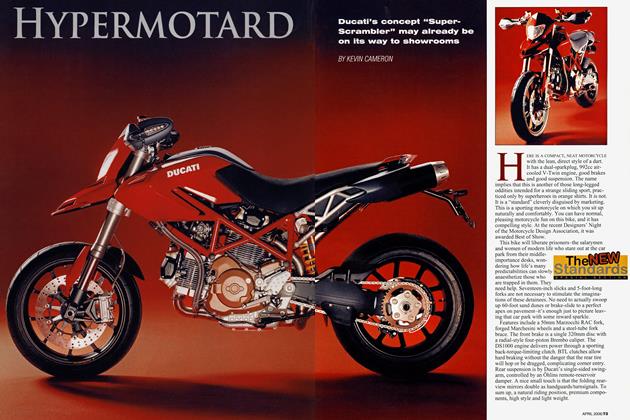

The prediction of rapid change soon to come can create a buzz of expectation that outruns what is actually happening. I remember this well from the 1980s when many in our sport confidently expected a torrent of chassis innovation, originating in ideas from Formula 1, to wipe away an outworn and conformist past to bring us revolutionary motorcycles unlike anything seen before. These new machines would by implication be as revolutionary as the “rear-engine explosion” was in Formula 1; in 1959, Australian driver Jack Brabham in an “underpowered” tube-framed vehicle from obscure Formula 3 producer Cooper Cars swept away the power and the glory of blaring frontengined red Italian Ferraris and Maseratis. So sudden and complete was this revolution that within two years front-engined GP cars were gone—dismissed as “tractors.”

Much of the 1980s expectation of something similar for motorcycling centered on replacing the stiction-ridden and pro-dive telescopic fork with some combination of rods, bell-cranks, hub-center kingpins, and, most of all, the ball-pivots known as “Rose” or “Heim” joints. There were other agendas as well—to achieve the English ideal of “low center of gravity” and constant wheelbase or to achieve front-end geometry unchanged by brake dive. To eliminate brake dive completely. To eliminate the chassis.

The point here is not the details of a failed revolution (the highest 500 world championship finish of a Heim-joint bike was fourth, in 1987, by Ron Haslam on the Fi-inspired ELF-Honda) but to show the power of expectation; the revolution would succeed, not even on its merits, but rather because so many of us were excited by this prospect of fast revolutionary change. It had to happen. It would happen. But then it didn’t.

Expectation can also lag behind reality. When digital equipment showed prototypes of its PDP-11 computer, which had the novel features of screen and keyboard, nobody paid much attention—this was little stuff. Primed by years of science fiction, the public’s idea of computers was as “Giant Electronic Brains” with goofy names like ENIAC. They resided in cool, silent rooms and were served by acolytes feeding them shoeboxes full of Hollerith cards. But— whammo—the personal desktop computer arrived, followed by the laptop and now the smartphone, equipping society for something called the internet and changing life in completely unanticipated ways.

On the same day this week I was forwarded two copies of a prediction of a kind I had been hearing about for some years. Tony Seba, an economist at Stanford University, says that manufacture of internalcombustion-powered cars, trucks, and buses will cease entirely within eight years and that people will stop driving in favor of autonomous electric cars that are 10 times cheaper than present-day cars and have a million-mile lifetime. Auto dealers will cease to exist by 2024.

This is fairly breathtaking, but similar ideas have been circulating for a while now. This rapid change is to come about because of something called “disruptive capitalism.” In this paradigm, a new idea is at first dismissed as pointless, too expensive, silly, etc. But it keeps nibbling away, gaining strength as did the transistor and the gas turbine, with ever-more-attractive economics. Then one day the old technologies are suddenly perceived as what they are— incapable of significant improvement and therefore having no future. Out with the old, in with the new. Both the gas turbine and the transistor advanced very much faster than expected.

The same happened when Charles Parsons’ 1893 steam turbine upended the complex triple-expansion piston steam engine.

BY THE NUMBERS

51 AMOUNT BYWHICH THE POWER OF FERRARI’S V-6 GP CAR OF 1959 EXCEEDED THAT OF THE FOUR-CYLINDER COOPER-CLIMAX OF DRIVERJACK BRABHAM

15 NUMBER OFYEAR5 FOR CHARLES PARSONS’ STEAM TURBINES TO TAKE OVER THE TASK OF POWERINGTHE WORLD’S SHIPS AND GENERATING ITS ELECTRICITY

14 NUMBER OF YEARS MY ARTERIES HAVE GONE UN-NIBBLED SINCE I HEARD THE LECTURE PREDICTING A NANOBOTCURE FOR ARTERIOSCLEROSIS

On the other hand, advances in microbiology emboldened some to predict that “nanobots” would shortly wipe out arteriosclerosis and cancer. The tiny hots, injected by a med tech during a $5 office visit, would cruise your bloodstream, nibbling away obstructing plaque or identifying and devouring cancer cells wherever found. Never mind the question, “Who needs cab drivers?” Now it becomes, “Who needs doctors or hospitals?”

Problem is, we’re still waiting for news of important progress toward nanobots.

This leaves us where we started—not knowing whether our expectations have outrun reality (in 1948 many believed every family would soon have its own airplane or “Hiller-Copter”) or whether reality is about to streak out ahead in the form of cars costing 10 percent of what they cost now, lasting a million miles, and coming like a faithful dog when our smartphones whistle.

An ideal electric future requires that the electricity to power Mr. Seba’s completely rational vehicles must be carbon free. How’s that looking?

The two visible patterns are that coal and natural gas have changed places recently, but their total share has changed very little; in 1996 coal supplied 52 percent of US electricity and gas 13 percent, but in 2016 it was natural gas 33.8 and coal 30.4, with their total share at 65 percent in ’96 and 64.2 last year. In 2013 wind supplied 4.13 percent and solar 0.23 percent, rising to 4.4 and 0.4 a year later, and 5.6 and 0.9 last year. Draw lines on your own graph and extrapolate. Renewables are gaining, but combustion-plusnuclear hangs in there at 84.6 percent in 1996 and 83.9 last year.

Is faster-than-expected progress taking place in battery development, as it did in the case of the gas

TONY SEBA, AN ECONOMIST AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY, SAYS THAT MANUFACTURE OFINTERNAL-COMBUSTIONPOWERED CARS, TRUCKS, AND BUSES WILL CEASE ENTIRELY WITHIN EIGHT YEARS...

turbine and transistor? The bestperforming general kind of battery in service at the moment, lithiumion (which can be made with any of several electrode chemistries to emphasize particular qualities), advanced steadily in energy density until about 2002 when its rate of advance declined. Hundreds of laboratories are at work on its problems of high cost and limited energy density, so there’s no lack of effort. Could there be a slam-bam breakthrough tomorrow? You betscience is like that. In the late 1930s people were trying to locate distant aircraft with a listening apparatus that looked like tremendous cat’s ears. And then came radar.

But there could have been a slam-bam breakthrough last year or the year before—all the way back to 1992 when Sony commercialized lithium-ion.

So which is it? Will our expectations produce success? Or could they outrun reality? ETU

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

2018 Harley-Davidson Softails

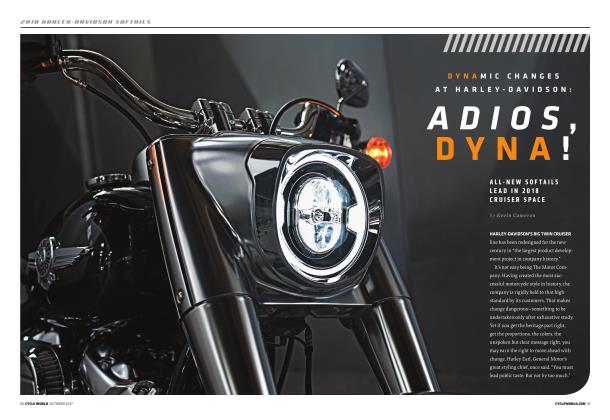

2018 Harley-Davidson SoftailsDynamic Changes At Harley-Davidson: Adios, Dyna!

OCTOBER 2017 By Kevin Cameron -

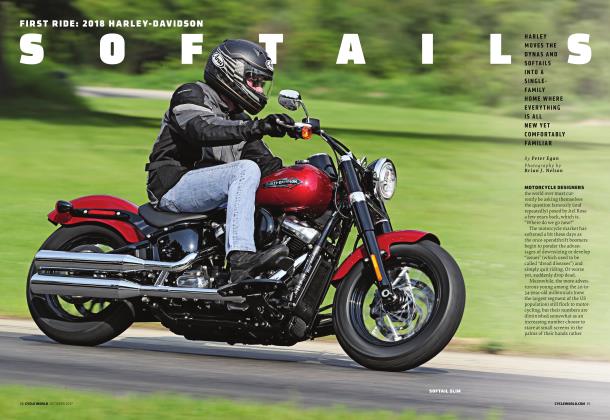

First Ride: 2018 Harley-Davidson Softails

OCTOBER 2017 By Peter Egan -

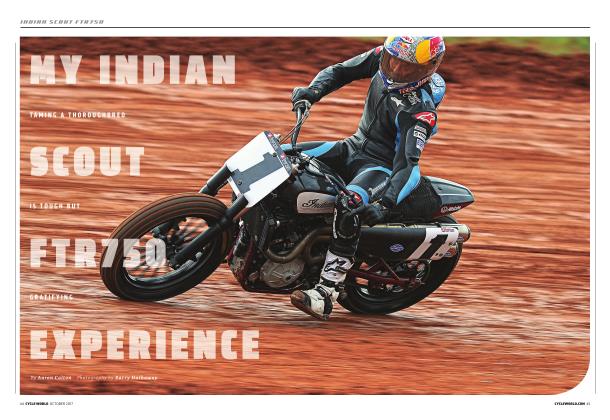

My Indian Scout Ftr 750 Experience

OCTOBER 2017 By Aaron Colton -

Race Watch

Race WatchWhere Is World Superbike Going?

OCTOBER 2017 By Kevin Cameron -

Service

OCTOBER 2017 By Ray Nierlich -

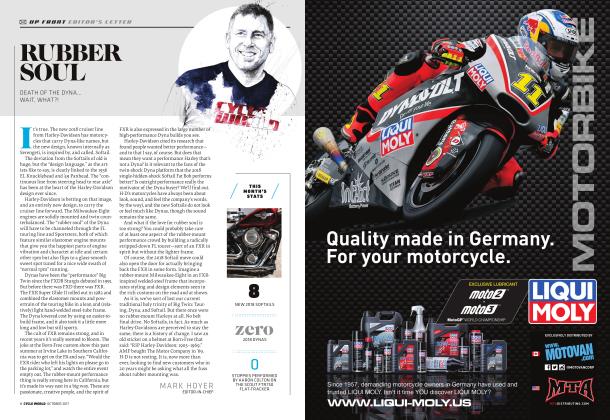

Up Front

Up FrontRubber Soul

OCTOBER 2017 By Mark Hoyer