WHAT’S HEAVY?

IGNITION

TDC

ADDRESSING THE STEERING-STIFFENING EFFECT OF KEY COMPONENTS ON A MOTORCYCLE

KEVIN CAMERON

Attitudes toward weight have changed, but the heavy stuff is still there. People now know that a "brochure weight" of 396 pounds can mean more like 450 to 475 pounds, ready to ride. And some racing classes have minimum weights (in MotoGP it’s 346 pounds) to discourage use of costly light materials.

Sixty years ago, when Moto Guzzi was on its five-year winning streak in 350 GP, light weight was central to its success.

At one point, Guzzi’s polymath engineer Giulio Cesare Carcano decided to try smaller wheels and tires as a means of improving acceleration. Rider Bill Lomas wasn’t so sure, knowing the importance of tire grip. But here was Carcano’s thinking: Tires and rims must not only be accelerated as a whole when the machine speeds up, but they are simultaneously accelerated in rotation around their own axles. As an example, going from a 21-inch front rim and tire to 18-inch rim and tire meant a 14-percent reduction in tire and rim weight, multiplied times two because of the “double acceleration” of rotating parts. A test was laid on at a track where acceleration was important, and Lomas’ lap times were reduced by the smaller wheels and tires, despite having a bit less rubber on the road.

This impressed Lomas, with the result that the 1957 version of the Guzzi 350 was lightened to just 216 pounds. Despite the greater horsepower of four-cylinder 350s from Güera and MV, Guzzi’s ultra-light single-cylinder bike took the championship for a fifth year. Watch the YouTube videos of Isle of Man racing and you will see that much of it takes place in higher gears, making horsepower more important than acceleration. But on slower, twistier tracks where acceleration is paramount, a very light bike with a wide-range engine takes home the shiny engraved pots.

In the present era, the cost of real estate gives us racetracks like Valencia, which pack a maximum number of turns into a minimum acreage. Bikes are turning all the time, forcing the development of wide, high-grip tires quite different from the hard, skinny patterned (all-weather) tires of 1956. Yet have a look at any literbike; its front tire is much smaller than its rear. Why? The heavier the front tire is made, the more rider effort required to steer it. Its section is a compromise.

When Nick Richichi moved up from 250s to the TZ750 the first thing he noticed was increased steering effort. “I’m using all the strength I’ve got to get that thing up after turn two!” (There was a quick right-left direction change at the old Loudon, New Hampshire, track.) He later found it useful to shorten the wheelbase on fast tracks, to get the most out of steering stiffened by high speed. And this is why riders who have ridden with the light carbon brake discs in MotoGP are so sensitive to front-wheel mass; they’ve had it good!

The first step in this progress toward lighter, more easily steerable front wheels was the abandonment of inner tubes when cast wheels came into use after 1973. A tube might weigh as much as 3 pounds, and, as noted above, this mass, located at maximum distance from the center of the front wheel, contributed significantly to steering effort. Another step came when first Michelin and then the other tire makers abandoned bias tire construction and used semi-radial construction in its place, which resulted in a drop in tire weight of 1 to 3 pounds.

The first magnesium wheels were not much lighter than their wire-spoked equivalents, and 1980s efforts to make really light cast wheels sometimes ended with bent wheels. Then riders found some of the first ultra-light carbon wheels to be too stiff (I’m remembering that the only thing that stopped one 600 Supersport factory team’s front chatter was a wire wheel!). Forging, which done right can increase fatigue strength, has been adopted for racing wheels. The result is wheels light enough to steer easily and provide the degree of flexure riders want, without cracking.

BY THE NUMBERS

WEIGHT OF A GOLD BRICK IN POUNDS

300 BRAKING DISTANCE IN METERS FORA RIDER GOING INTO TURN 12 AT COTA, OFFTHE LONGEST STRAIGHT IN MOTOGP

17 THE REGULATED SIZE IN INCHES OF MOTOGP WHEELS AS OFTHE 2016 SEASON

Sixteen-inch and 16.5-inch wheels and tires have come and gone in racing. Sixteens were too twitchy for many riders in 1981 and 1982, and sanctioning bodies and tire makers alike wanted to bring race and production tires closer to each other. The result is the present 17-inch compromise.

Racers have always been sensitive to the effects of weight on the front wheel. When the late Geoff Duke rode for Güera, he normally used the smallest (drum) brake that gave a decent lap time, rather than always having the largest brake available. Today, riders in MotoGP use heavier steel discs only in wet conditions and the lighter carbon discs in the dry.

The normal carbon disc size is 320mm (12.6 inches), but larger 340s (13.4 inches) may be used if necessary (Motegi, where Ben Spies had sudden brake overheating a few years back). Even though carbons are light, riders prefer the smallest discs that can do an adequate job.

The steering-stiffening effect of front-wheel weight is proportional to the square of each given bit of weight’s distance from the center of the axle. Thus, tire and rim weight are more important than the weights of spokes, which in turn are more important than hub or bearing weights. Wanting to make his bikes quick steering, Erik Buell has employed single metal discs of 375mm to 385mm outer diameter in place of the usual sportbike set of two 320mm steels. Test ride a Buell or do the math to see whether this is a step forward.

RACERS HAVE ALWAYS BEEN SENSITIVE TO THE EFFECTS OF WEIGHT ON THE FRONT WHEEL.

When in 1988 Honda decided to engineer lighter steering into its two-stroke NSR500 GP bike, it gave it the lightest possible iron discs. At the Laguna Seca round of that GP season, those light discs turned black from overheating, wore out their pads, and the Honda riders were essentially out of brakes by two-thirds distance. Carbon discs were adopted the next year.

For the fun part: Lots of insight into steering and handling can be had by removing a bicycle’s front wheel from the drop-outs, grasping it by the axle ends, and having a friend give it a spin. Pretending your arms are fork legs, try “steering” or leaning to right or left, as if entering corners. Play is instructive!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Ten Rest

September 2016 By Mark Hoyer -

Intake

IntakeIntake

September 2016 -

Ignition

IgnitionThe Alternative Interior

September 2016 By Bradley Adams -

Ignition

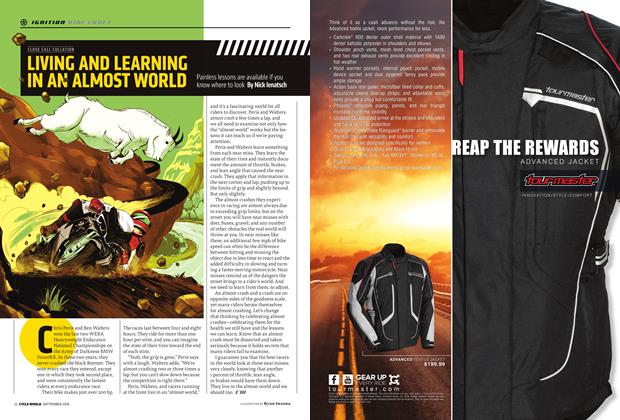

IgnitionClose Call Collation Living And Learning In An Almost World

September 2016 By Nick Ienatsch -

Ignition

IgnitionThe Dark Rider

September 2016 By Paul d’Orléans -

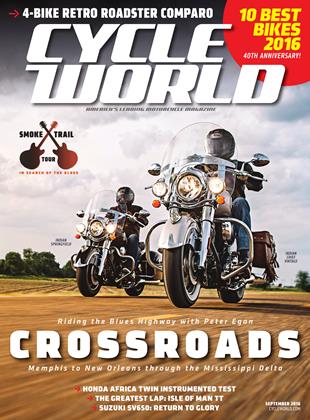

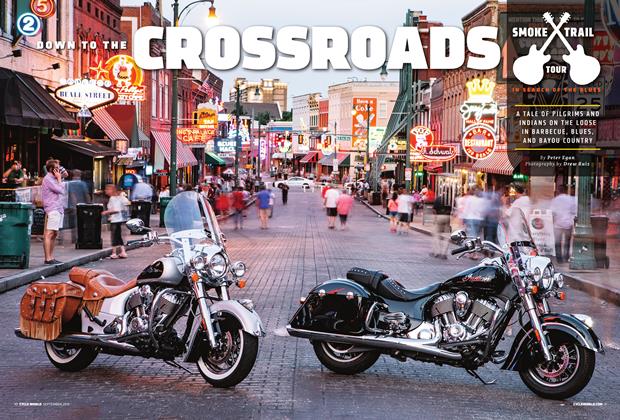

Smoke Trail Tour

Smoke Trail TourDown To the Cross Roads

September 2016 By Peter Egan