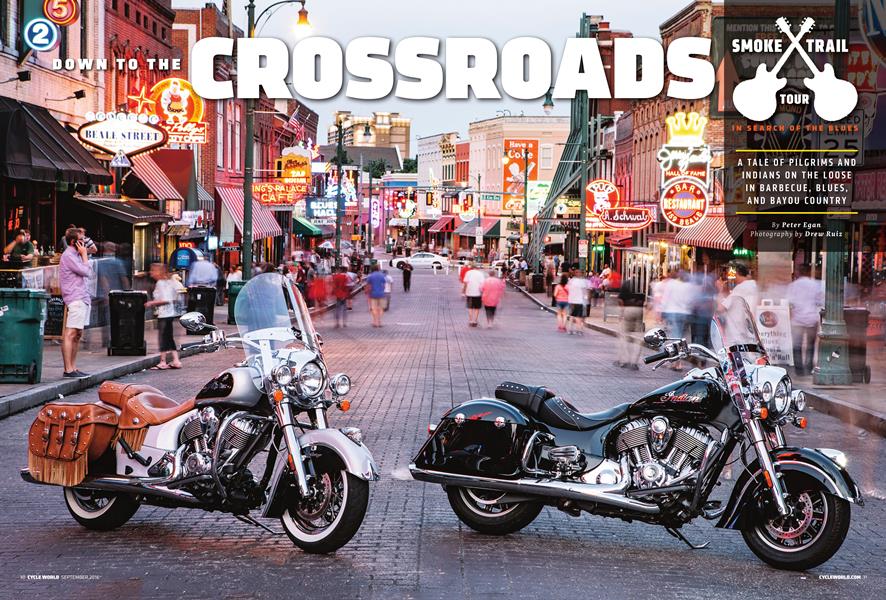

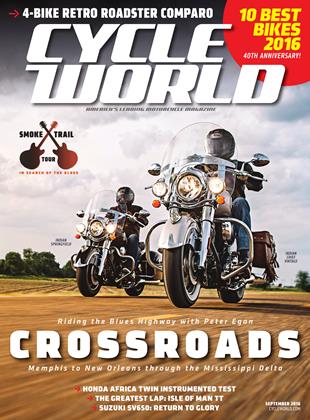

DOWN TO THE CROSS ROADS

SMOKE TRAIL TOUR

A TALE OF PILGRIMS AND INDIANS ON THE LOOSE IN BARBECUE, BLUES, AND BAYOU COUNTRY

Peter Egan

If you’re the sort of motorcyclist who likes to “strafe corners,” a trip down Highway 61 from Memphis to New Orleans will probably save you a lot of money on ammo. There are a few gentle curves along the Mississippi, but most of the corners in this land of bayous and cotton fields are crossroads, both literally and figuratively.

So why go there?

Well, I suppose the answer for some of us would simply be: the music.

Memphis is the birthplace of rock ’n’ roll, New Orleans is the home of jazz, and between them lies a stretch of rich bottomland called the Mississippi Delta, the land where the blues began. Also, there’s a lot of good food and drink along these 400 miles of river road—smoked barbecue, fried catfish, seafood gumbo, beignets, French-roast coffee, and the famous hurricane drinks of New Orleans.

As a fledgling blues fan and apprentice omnivore, I first headed down there from Wisconsin in 1978 on my 40oF Honda, and since then I’ve made three return trips—one in my coffee-colored 1963 Cadillac and one on a brand-new Triumph T100 Bonneville in 2003.1 also went back on vacation with my wife, Barb, a couple of years ago. There’s some magical combination of music, food, history, and ambiance that keeps drawing me back.

So when Editor Mark Hoyer called a few weeks ago and asked if I’d like to make the trip again with him on a couple of 2016 Indians, I automatically said yes. I have to get my Highway 61 music and food fix every few years or I become erratic and morose. Even more than usual.

Apparently, Hoyer was suffering from this same syndrome, even though he’d never been in this part of the Deep South before. As a guitarist and blues fan, he felt the inevitable, distant pull of the Delta, and it didn’t hurt that he also loves smoked barbecue, Cajun food, and the more opaque brands of bourbon and rye. It seems we share a genetic preference for all things smoky, whether music, food, or drink.

“We need to fly into Memphis,” Mark said, “and pick up the Indians at a local dealership. Then we’ll drop them off in New Orleans and fly home. You make the hotel reservations.”

The first hotel choice was easy. As Mississippi author David Cohn famously wrote back in 1935, “The Delta begins in the lobby of the Peabody Hotel in Memphis and ends on Catfish Row in Vicksburg.” So I was compelled by literary tradition to get us a couple of rooms at the elegant old Peabody. Andrew Jackson, William Faulkner, and The Rolling Stones had all stayed there, so we knew they’d have a decent bar.

LAUNCH POINT FOR THE TOUR: Memphis offers sounds and smells like few cities on earth. The historic Peabody Hotel was a great spot to call home, being just a few blocks off Beale Street and its blues clubs and barbecue restaurants. The Gibson Guitar Factory store is also just a short walk. A few minutes by Indian down the road is Sun Studio, where modern popular music was changed forever. Memphis is also where you pick up The Blues Highway, running south on 61roughly following the course of the Mississippi through the Delta.

I flew into Memphis on a Sunday afternoon and met Mark at baggage claim when his plane got in from California. “Welcome to Memphis,” I said. “You are now an honorary Memphian.”

“After sitting in an airplane all day,” he said, “I feel more like a Memphibian.”

We mulled that over for a minute and decided that a Memphibian is a creature that can walk on dry land but also drink like a fish on Beale Street.

At car rental we picked up a blue Toyota Sienna for the use of our photographers, Nik Wogen and Drew Ruiz, who were coming in later. As we cruised toward the Peabody in air-conditioned comfort, Mark plugged some John Lee Hooker into the sound system then suddenly said, “Can you imagine John Lee Hooker driving around in this minivan?”

I shook my head. “The Japanese don’t do bluesmobiles very well,” I said. “On the other hand, you probably wouldn’t want John Lee Hooker to design your climate-control system.”

We entered the beautifully ornate lobby of the Peabody with its big marble fountain and famously trained ducks, which come ceremoniously down the elevator from the roof every morning and return in the evening. It’s a ritual that packs the lobby with tourists twice daily, and they had just left. You could sense the vacuum.

We tossed our lumpish gear bags into our rooms and walked down to Beale Street, with its neon-lit blues clubs and restaurants. In the past century, this was the glittering music row of the Delta, home of Southern blues and good times. But it went into decline, and by the time I got here in 1978 it was a bombed-out shell of its former self, and the empty street was littered with broken glass.

The desk clerk at the Peabody warned me not to go there, even in daylight. I did anyway. Then got on my motorcycle and rode south. Another piece of Americana gone.

DUK FOUND US PULLING UP AT A PLACE CALLED THE SHACK UP INN... IT'S A COLLECTION OF WEATHER-BEATEN SHARECROPPER SHACKS THAT HAVE BEEN REHABILITATED INTO CLEAN BUTFUNKY MOTEL UNITS...

But urban renewal and a blues resurgence turned the lights back on, and now you’d never know anything happened. Fully restored, brightly lit, and absolutely jumping on a Sunday night, the blockedoff street was full of pedestrians and music.

Mark and I had a late dinner of smoked ribs at the Blues City Café, and I ordered a local beer called Snopes, as I was right in the middle of reading William Faulkner’s Snopes trilogy. The beer was superb, which is more than you can say for the Snopes family in the novel. Toward the end of dinner, photographers Drew and Nik cabbed in from the airport and joined us.

In the morning, we drove across the Mississippi on the I-40 bridge to Barton Powersports in West Memphis and picked up our Indians, which we immediately named Blackie and Fringie.

Blackie was an all-black version of the new Springfield model with a cop windshield and hard bags, while Fringie was a silver-and-black Chief Vintage with a similar windshield but tan leather saddlebags and seat with fringe and more relaxed rake at the forks. Both had the 111-inch faux-flathead V-twin engine, floorboards, and low, comfortable seats. When you pick them up off the sidestand, both feel dense and hefty at around 800 to 850 pounds but travel down the road at low, relaxed revs with nice torque. It’s also calm and restful behind those big windshields, perfect for a flowing, laidback trip down the river.

We crossed back over the Mississippi for a good view of the downtown, with the landmark Memphis Pyramid on our left, a glittering homage to the city’s Egyptian name. The pyramids on the Nile, however, probably don’t contain a Bass Pro Shops.

Mark and I turned down Union Avenue toward one of the great shrines of Memphis, the small but historically potent Sun Studio. As virtually everyone on earth knows, this is where a young Elvis walked in off the street and asked to make a record for his mother in 1953. Nice-looking kid with a good voice. Others who showed up for a shot at fame were Howlin’ Wolf, Johnny Cash, Roy Orbison, Ike Turner, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, Rufus Thomas, Charlie Rich, etc., etc. Visionary Sun Studio founder Sam Phillips probably did more to change American culture than anyone since Columbus. But don’t make me prove that in a doctoral thesis.

We took a tour and stood in the original recording studio where all those people once sang and played, and everyone got very quiet, as if listening for ghosts in the room. Those guys are all gone now, except for Jerry Lee. The Killer rocks on.

We’d hoped to visit Stax Museum as well, but we ran out of daylight because I got snagged by the Gibson Guitar Factory and its retail store. Just before this trip, Fd had several of my guitars stolen, so I was on the hunt for replacements. I found a really nice Derek Trucks signature model SG but decided against entrusting it to the tender mercies of the airlines on my way home.

INTO THE DELTA: Elvis Presley's Graceland was purchased by the soon-to-be King in 1957 for $102,500. It’s a remarkable time capsule, and the family still stays there for occasional visits. It was our last stop in Tennessee, before we got moving into Mississippi. The steady beat of the Indians matched the easy swing of the highway. Don’t miss the Shack Up Inn or anyone of the several Robert Johnson memorials.

That night we hit Beale Street in the company of the redoubtable Leo Goff, a Memphis native and famous engine builder, tuner, drag racer, and motorcycle collector. He’s also a professional bass player whose tracks may be heard on 173 albums and CDs, and he plays in three different Memphis blues bands.

As we walked down Beale, every single bartender, musician, street person, and club barker shouted, “Leo, my man!” We ended up at the Rum Boogie Café, eating barbecue and listening to Gracie Curran and the High Falutin’ Band, an excellent blues combo who all nodded at Leo when he walked in. If he ran for mayor of Memphis, I think he’d win.

We took Elvis Presley Boulevard out of town the next morning and stopped at Graceland, lining up with visitors from all over the world to take a tour. It’s a beautiful house and grounds and a great place to grasp the true cultural weight of Elvis’ life and career, which is equal parts American success story and tragedy. In the museum room of gold records and movie posters, you can sense the relentless pressure on him to keep this huge money machine in motion. Which he is still doing. The tour tickets were $80 each, and the line is endless.

We toured the house, where poor Elvis had his tastes in furniture and carpeting permanently frozen in the ’70s—something none of us would like to have done to us—and we filed quietly past the family graves on the side lawn.

John Lennon once said, “Before Elvis, there was nothing.” I wouldn’t quite go that far, but when my older sister bought a copy of “Hound Dog” in 1956,1 played it on my little record player about a thousand times, watching that label spin around and trying to imagine what planet this wonderful, mesmerizing sound had come from. And now I was there.

We hooked up with Highway 61 South, crossed the Mississippi state line, and were on the open road at last, into the Delta.

The first few miles of the highway were lined with huge gambling casinos, but the true Delta of small towns, sprawling cotton plantations, and crop dusters reappeared around Robinsonville, where the great bluesman Robert Johnson once lived and worked on the Abbay & Leatherman Plantation.

We stopped for lunch at the nearby Hollywood Café, noted blues joint and sometime local hangout for author John Grisham. It’s been said that Mississippi has produced more great writers per square foot than any state in the US, an honor roll that includes William Faulkner, Eudora Welty, Truman Capote, Tennessee Williams, Walker Percy, Shelby Foote... As with blues musicians, the list goes on and on. There’s just something about this place. Maybe it’s the soil.

WILL IT FRY? The answer at the Hollywood Café was “Yes!" all the way down to the pickles. And if it won't fry, it will smoke! Hoyer and Egan both picked up the guitar for impromptu solo performances there, along with an actual retired pro musician whose rendition of “Georgia on My Mind" was so nice, even the Memphibians applauded.

The Delta was once called “the Great Panther Swamp,” an impenetrable jungle of hardwoods that happened to sit on about 25 feet of the richest black soil on earth, deposited by centuries of river flooding. Much of it was cleared after the Civil War by a huge workforce of former slaves and Anglo planters who were willing to risk yellow fever and floods for profits in the cotton trade. Meanwhile, the Scots-Irish and their music moved down the Appalachians into the hill country and bluffs above the Delta. Quite a mixture.

Fve often thought that if the Delta had been settled by a European monoculture—say the Swiss or Germans—instead of a crazy-quilt of Brits, Celts, and African-Americans, we’d be coming down here for Polka Fest and the Delta would be about as funky a tourist attraction as the cornfields of central Illinois. You need a little of everything and everybody to make American music, and this is the crossroads.

We got off the four-lane Highway 61 and took Old 61 south toward Clarksdale on our big comfortable Indians. I liked Blackie best, for its slightly smoother engine (better break-in?) and quicker, sportier-feeling steering, but Fringie had a certain magnificence, and its laid-back rake made it feel more stable when we hit stretches of gravel road along the levees. Both bikes have excellent brakes, nicely damped suspension with reasonable travel, and a bottomless well of smooth, low-rpm torque that makes downshifting optional at most road speeds. They’re all-day comfortable touring bikes whose only drawback is weight, when you want to pull a quick U-turn or back out of a parking spot. Don’t be ashamed to ask for help.

Dusk found us pulling up at a place called the Shack Up Inn, near Clarksdale. Situated on the old Hopson Plantation, it’s a collection of weatherbeaten sharecropper shacks that have been rehabilitated into clean but funky motel units, gathered around a big, old corrugated iron cotton gin building that houses an excellent bar, restaurant, and music stage. Lots of musicians stay there, and we arrived just as a harmonica workshop was in progress. Thank god it wasn’t Banjo Days.

DISTANCE: It only takes about five hours of riding to sprint from Clarksdale’s Shack Up Inn to New Orleans and the Hotel Monteleone, but the weathered steel buildings are a world away from the French Quarter. There was no hurry, this was a journey for the sake of the journey and every moment was an arrival to exactly where we wanted to be.

The restaurant was closed for a group dinner, so we rode into Clarksdale, epicenter of blues country, just as all the restaurants closed—except for one upscale bistro that could just as easily have been in Portland. The salmon special was excellent, however, and we shared the dining room with a large, cheerful HOG Chapter from Padova, Italy.

Our sense of authenticity was rescued when we stopped at Crossroads Liquor, right on the famous junction of Highways 61 and 49, and I bought a bottle of Evan Williams bourbon, my favorite. This corner is where the great bluesman Robert Johnson was supposed to have sold his soul to the Devil in exchange for his unearthly musical talent. I don’t believe this story, however, because Johnson and his evil pal would have been instantly run over by a truck. This is one of the busiest crossroads in Mississippi. Also, Johnson himself never claimed this happened. I believe it was a theory developed by jealous musicians who didn’t practice enough.

Back at the Shack Up Inn we had a late evening nightcap on the front porch of Nik’s cabin, drinking bourbon and watching a lightning storm play

out over the Delta. The cabin was short on drinking glasses, so Nik drank his bourbon from a cereal bowl. When his left eye wandered upward toward the moon—which was re-emerging spookily from behind a storm cloud—and his other eye slammed shut, we decided it was time to go to bed.

In the morning we rode down the river road to Rosedale (mentioned in the Robert Johnson song “Crossroads”) and had lunch at the White Front Café, where chef/owner Barbara Pope serves nothing but her famous tamales. Then we rode a few miles down to Beulah, where the crossroads in the movie of that name were supposed to have been filmed. We didn’t find them, so we chose our own. As Mark said, “The crossroads are personal and spiritual.”

We didn’t have time to wait until midnight for the Devil, so we headed west toward Greenwood, where the unfortunate Mr. Johnson is possibly buried in one of three reputed graves. Legend has it he was killed by a jealous husband who sent a poisoned drink up to the stage one night at a juke joint in Three Forks. His death certificate says he was buried at the Zion Church, of which there are several in the area. Since no one knows for sure, I led our little band of pilgrims to the one with the best headstone, just off Highway 7 north of Morgan City.

FINDING THE BLUES: The din on the streets of New Orleans makes you disregard or distrust most noises. Then this guy’s eerie and wonderful slide guitar lilts effortlessly through to grab you by the soul. That slide is his spark plug socket...

A lovely, quiet little spot where I like to ponder the list of songs on his monument. Our garage band plays about five of them, as best we can, and a hundred great bands have played the rest. “Fove in Vain” is a thing of beauty.

Noon found us in the beautiful hilltop town of Vicksburg, where Grant spent many months in 1863 trying to take this important river citadel away from the Confederacy. He eventually succeeded, but the surrounding hills are covered in tombstones.

At the River Town Grille in Vicksburg, I had the best meal of the trip—catfish smothered in a crawfish étouffée—and we kept the theme going after lunch by looking for the legendary Catfish Row where the Delta is supposed to end. This once-notorious row of riverfront dives is now a pleasant little playground with a big fountain for children to frolic in. We left before someone’s mom called the police about the guys in motorcycle boots and black leather.

Next stop, New Orleans.

We had to make tracks that hot afternoon. The Big Easy was still several hundred miles away, so we got on I-10 and hammered our way east on the elevated highway over the vast swamps. The Superdome and skyline hove into view, we turned off on the Vieux Carré exit, and soon found ourselves pulling into the parking garage of the Hotel Monteleone. This place is famous as “the writers’ hotel,” sometime residence of Hemingway, Faulkner, and Williams, and now Hoyer and Egan...in no particular order, mind you.

We peeled our sweatsoaked leather jackets off, cleaned up, and hit the streets of the French Quarter—my favorite neighborhood in one of the only two major cities in which I would consider living. Paris is the other one. It must be the French influence on food. After a shrimp, oyster, and crawfish-based dinner at the unpretentious but excellent Remoulade, we all got ourselves some big old hurricanes at an outdoor stand and strolled down Bourbon and Royal streets, people watching.

To paraphrase a song, the street goes on forever, and the party never ends. Our own evening ended with a Sazerac cocktail or two at the Monteleone bar—a hyper-lively scene for sharp-dressed twentysomethings and thirtysomethings on dates. Or looking for dates. Or something. They had a knockout jazz band.

New Orleans in early morning is the very picture of the term “the morning after.” It’s subdued and muted, with only the sounds of the street cleaners washing the sticky pavement. The famous Café du Monde had a waiting line of slightly hungover patrons, so we got our French-roast coffee and beignet fix at the nearby Café Beignet on Royal Street and walked around St. Fouis Cathedral on Jackson Square.

At noon, we finally had to mount up and return our Indians, riding out to Indian Motorcycle of New Orleans on the Airline Highway—which is good old Highway 61. Nice people there, and they gave us some black T-shirts with the Indian head logo and “New Orleans” printed beneath. Hard to beat as a final souvenir of this trip.

We blues-mobiled our Sienna back to the French Quarter, had a last fine dinner of aquatic swamp creatures in smoky, dark beurre roux, and then took a last walk down Bourbon Street. On a street corner sat a thin, young, white guy in a large black hat, playing an old Epiphone guitar through a small amp. Behind him was a beat-up tooth Anniversary Harley Sportster, painted flat black, with a huge box on the back to carry all his belongings.

He was playing some of the most beautiful slide guitar I’ve ever heard, in a haunting and complex melodic style. We listened for a long time and put some money in his guitar case. I asked his name and he quietly said, “Stoker,” without looking up. “Stoker Homeboy.”

On the way back to the hotel I said to Mark,

“That guy’s a genius, and he’s sitting in front of his old motorcycle, playing on a street corner. We came looking for the real blues, and I think we finally found ’em.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Ten Rest

September 2016 By Mark Hoyer -

Intake

IntakeIntake

September 2016 -

Ignition

IgnitionThe Alternative Interior

September 2016 By Bradley Adams -

Ignition

IgnitionClose Call Collation Living And Learning In An Almost World

September 2016 By Nick Ienatsch -

Ignition

IgnitionThe Dark Rider

September 2016 By Paul d’Orléans -

Ignition

IgnitionWhat's Heavy?

September 2016 By Kevin Cameron