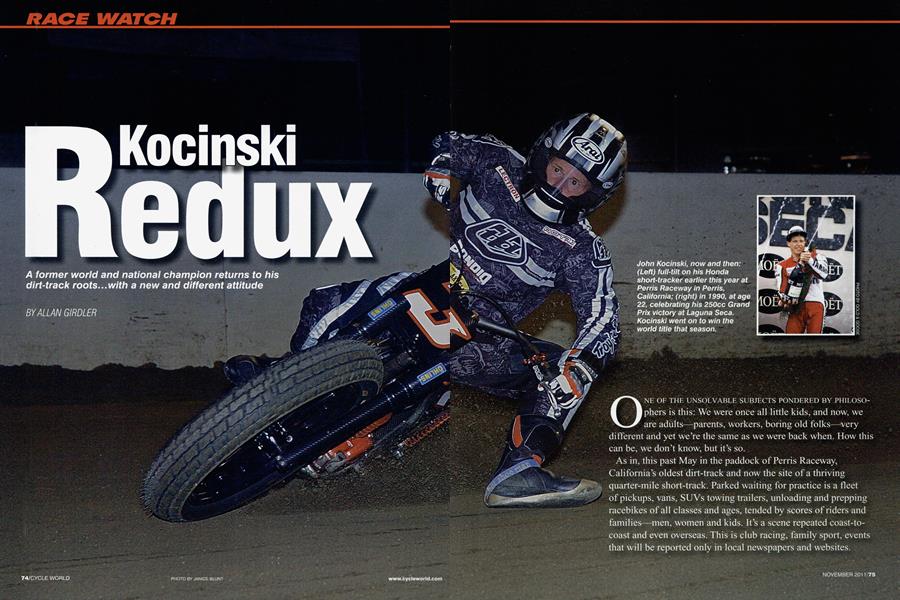

Kocinski Redux

RACE WATCH

A former world and national champion returns to his dirt-track roots...with a new and different attitude

ALLAN GIRDLER

ONE OF THE UNSOLVABLE SUBJECTS PONDERED BY PHILOSOphers is this: We were once all little kids, and now, we are adults—parents, workers, boring old folks—very different and yet we're the same as we were back when. How this can be, we don't know, but it's so.

As in, this past May in the paddock of Perris Raceway, California’s oldest dirt-track and now the site of a thriving quarter-mile short-track. Parked waiting for practice is a fleet of pickups, vans, SUVs towing trailers, unloading and prepping racebikes of all classes and ages, tended by scores of riders and families—men, women and kids. It’s a scene repeated coast-tocoast and even overseas. This is club racing, family sport, events that will be reported only in local newspapers and websites.

Except that one of the dads, driving an unsponsored pickup and shepherding two small kids, is John Kocinski.

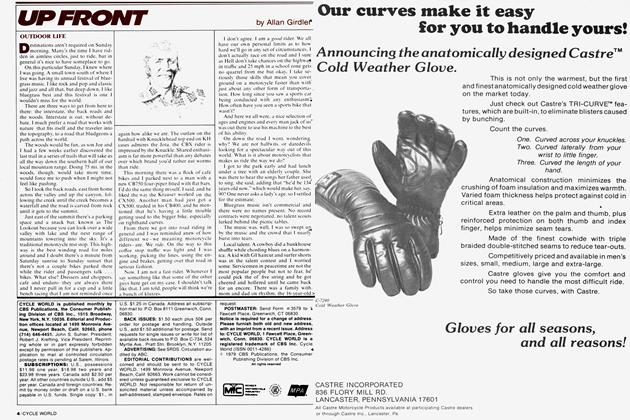

Yes, that John Kocinski, the Boy Wonder, signed by a factory roadracing team at 17, AMA 250cc Grand Prix champion in 1987, ’88 and ’89, winner of the world 250cc GP title in 1990, fierce combatant in the legendary 500cc GP era, when the bikes had the manners of junkyard dogs and the riders never gave an inch.

Kocinski raced Grands Prix for Yamaha, Suzuki, Cagiva and Honda (the last on a privateer NSR500 tuned by legendary Erv Kanemoto). He scored Cagiva’s only dry-track 500cc-class victory. When Cagiva dropped out of GPs and Kanemoto’s team didn’t gain sponsors, Kocinski rode World Superbike for Ducati and then Honda, for which he took the world title in 1997.

Some résumé, eh? Except that a glance at the records justifies the question of why all the different makes and teams. Why, quoting Wikipedia here, did he “fall out” with the various factory teams?

He was, as one blogger puts it, “gifted but difficult.”

As they say about youngsters, Kocinski did not play well with others, not with his rivals or his teammates—at least one of whom said things at the time for which he later apologized.

The talent, the gift, was clearly worldclass. The difficulties came because Kocinski was—you could look this up, kids—the John McEnroe of motorcycle racing: hard on others, harder on himself, never satisfied and not afraid to say so. He was quick to win backing because of his talent, just as quick to lose it because he would not, as the song says, back down.

Kocinski retired from the pro circuit and went into business, developing real estate and houses in Beverly Hills. Turned out, he was good at it, selling to more movie stars and moguls than we can list here.

The lone wolf became a husband and father and clearly had enough to keep him busy. Then, one day, in 2009, he turned up at the AMA Grand National Championship season-ender at Pomona, California, armed with a Rotaxpowered Ron Wood framer. He ran the Pro Singles class and did well on a bad track.

So, here we are starting the 2011 season at the Southern California Flat Track Association’s quarter-mile track in Perris. Here is Kocinski, wife, kids, truck and tools.

“Lemme ask ya,” says the reporter, “and I don’t mean this in any negative way, but.. .why are you here?”

Kocinski grins.

“I like taking a Chihuahua to a big dog fight.”

Some Chihuahua. Kocinski's fighting dog of choice is a nominal vintage bike, in that it's a two-stroke Honda CR250, aka an Elsinore, dated 1979. But it's not merely restored or rebuilt. It was mas saged and modified by Bud Aksland, who 20-plus years ago wrenched Kocinski's Yamaha TZ250 into those national titles.

“This,” says Kocinski with a gesture, “has a bit of an attitude.”

The frame is Knight, another classic flat-track name, circa 1980. It has twin rear shocks, Fox brand and straight out of the 20th century; Kocinski doesn’t see the need or advantage of current single-shock suspension. Fork is a beefy Öhlins. It isn’t vintage, but Kocinski says front suspension isn’t that important in short-track and earlier Cerianis would work just as well.

“Kocinski was—you could look this up, kids— the John McEnroe of motorcycle racing: hard on others, harder on himself, never satisfied and not afraid to say so. ”

No compression release, something the two-stroke racers relied on for years. Nor front brake, as the rules dictate, but there’s a modem lightweight disc brake in the rear and, speaking of that, the first time Kocinski raced Perris, the brake hanger broke and he turned the best time of the night, not just in class, minus brake.

Another quip: “I’ve been training to lose weight,” he says, “’cause lighter is faster. Why would I want something that would slow me down?”

There’s an expansion chamber and exhaust tuned for short-track, and the carburetor is a Lectron, vintage now but still good equipment and anyway, Kocinski was pals with the men—father and son—who designed and made it. Nineteen-inch wheels and class C tires, again as required.

The bike has never been on a dynamometer, although that may happen, just to check on tuning. But the engine must be as strong as an air-cooled vintage 250cc two-stroke Single can get. Besides, this is club racing, and the rules for vintage two-strokes apply mostly to the engine and are relaxed about details.

Some little dog, eh?

There are other forces involved with John Kocinski getting back on track.

One of the secrets of success in any sport is starting early; witness Casey Stoner, Nicky Hayden or Valentino Rossi. Kocinski’s dad was a motorcycle dealer, and the kid began racing aged 4. The venue was dirt-track, and he was good from the very first. Kocinski’s talent was spotted early, and no one missed the fact that roadracing pays better—in money and glory—than dirt-track does. He was signed by the Yamaha team, as in Kenny Roberts, when he was 17, and the rest is history.

As a slight digression, mark here that at least three legendary racers, Tazio Nuvolari, John Surtees and Joe Leonard, have gone successfully from two wheels to four, while no one has done well trading four wheels for two—just ask Michael Schumacher. Same goes for dirt to pavement, again cite Stoner, Hayden, Roberts, Lawson, Rainey and peers, while roadracers have a rough time adapting to sliding on purpose.

And then there’s the rule about never forgetting how to ride a bicycle.

Sum up with the fact that Kocinski always treated professional roadracing as combat, all against all as one ancient sage put it.

Dirt-track, in Kocinski’s words, is “art in motion.”

Dirt-track is different, at least at the club level, where it’s friends and family and the rivals—okay, most of the time— will give an inch when required.

So, here is John Kocinski, still the same yet not the same, running club events with a small vintage bike, not for money or glory but because he enjoys the sport and he likes to challenge both the sport and himself.

Art in motion is how he puts it, and art in motion is exactly right.

If you checked the diagrams used by dirt-track schools, such as American Supercamp, you would see the perfect line, precisely where you should roll off the throttle, lean the bike, tap the brake and kick the rear out, slide, then push the front wheel to catch the slide, roll the power back on just as the wheels touch the inside berm to exit on a late apex.

From the stands, we watch Kocinski do exactly as the book says. Make that better than the book.

Ordinary racers, aka you and me, hit the ruts, lose the front for an instant, get on the power too soon or too late and we react, make that over-react, and it shows.

Kocinski and peers somehow know what the bike's gonna do when, if not before, it happens. They are ready with exactly the right moves, precise and correct, never out of line or shape to the extent that it looks easy.

The SCFTA track doesn’t draw many spectators from outside racing, meaning the stand is mostly filled with racers and their parents or children, so they know what they are watching, which is why, after Kocinski runs off with the race and does a lap standing up and holding the checkered flag, he gets a standing ovation.

Back to the point, as in why he’s here: Kocinski says he enjoys the challenge of getting better all the time. He races in the vintage 250 class rather than the pro class, which, according to the lap times, he could win, against the licensed experts on 450cc pro-level machines.

But that’s not the point, and he doesn’t need to take money from kids who need it (nor would he embarrass all concerned by winning and not taking the money).

Here’s a foolish issue: Kocinski is after the track record. The official track record is listed as being 14.34 seconds, by national #37, Jimmy Wood, who set the record when he edged the previous titlist, national expert Henry Wiles, in a pro race earlier this season.

At the May meet, the announcer said Kocinski had been clocked at 14.42 seconds, better than his earlier time but short of the record. Kocinski’s crew said they’d got their man at 14.27 seconds. At that point, we learn that the clocks are handheld stopwatches, where the timer picks a post, say, and when the front wheel blocks the post from view, click! Fair and impartial and honest, but not the space-shot accuracy to distinguish between 14.42 and 14.27 seconds. Transponders are on the club’s budget this year, so one day we’ll have a better system. At a later meet, in July, Kocinski finally did set a new lap record—14.24 seconds.

Meanwhile, the Beta version of John Kocinski, a much-easier interview by the way, and given to invented quotes like, “Fear life? You should make life fear you,” closes with, “At this stage, I’m just having fun.” H

“Kocinski and peers somehow know what the bike’s gonna do when, if not before, it happens. They are ready with exactly the right moves, precise and correct, never out of line or shape to the extent that it looks easy.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

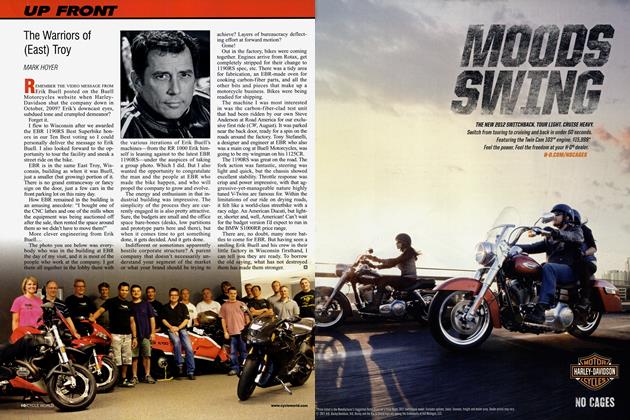

ColumnsUp Front

November 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

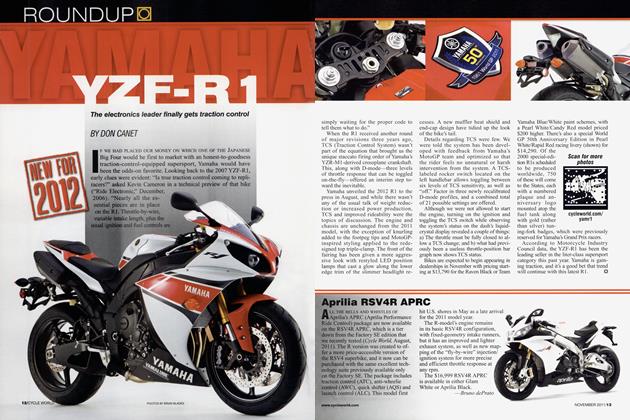

Roundup

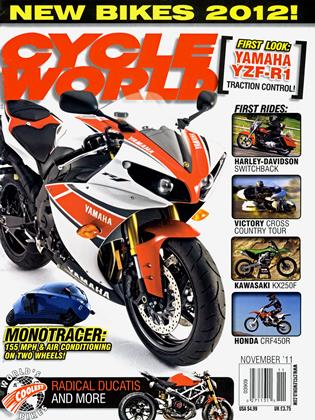

RoundupYamaha Yzf-R1

November 2011 By Don Canet -

Roundup

RoundupThe Future of Mx?

November 2011 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupMission Accomplished: Rapp Wins At Laguna

November 2011 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupFonzie's Triumph To Auction

November 2011 By Robert Stokstad -

25 Years Ago November 1986

November 2011 By Don Canet