HONDA GOES ITS OWN WAY

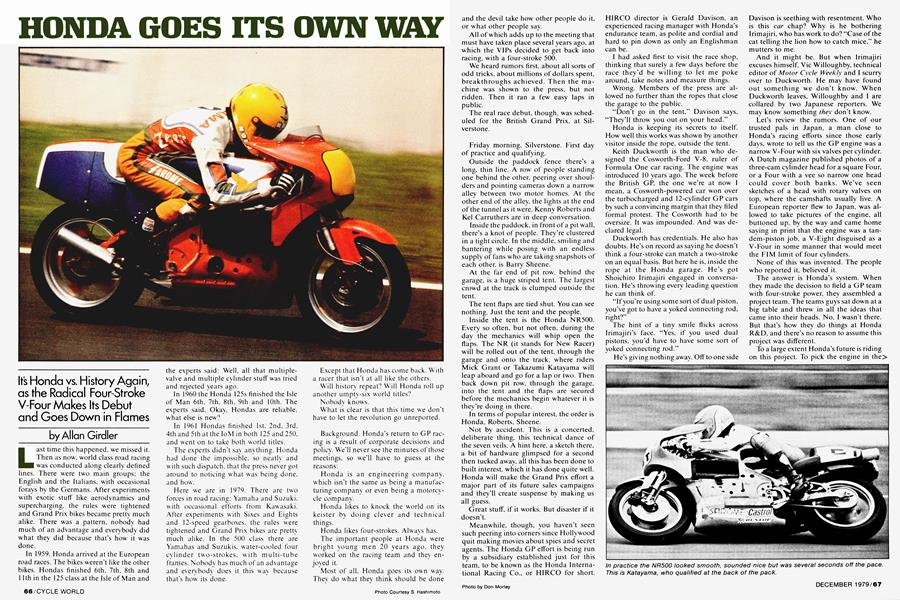

It's Honda vs. History Again, as the Radical Four-Stroke V-Four Makes Its Debut and Goes Down in Flames

Allan Girdler

Last time this happened, we missed it. Then as now, world class road racing was conducted along clearly defined lines. There were two main groups; the English and the Italians, with occasional forays by the Germans. After experiments with exotic stuff like aerodynamics and supercharging, the rules were tightened and Grand Prix bikes became pretty much alike. There was a pattern, nobody had much of an advantage and everybody did what they did because that’s how it was done.

In 1959, Honda arrived at the European road races. The bikes weren’t like the other bikes. Hondas finished 6th, 7th, 8th and 11th in the 125 class at the Isle of Man and the experts said: Well, all that multiplevalve and multiple cylinder stuff was tried and rejected years ago.

In 1960 the Honda 125s finished the Isle of Man 6th, 7th. 8th, 9th and 10th. The experts said. Okay, Hondas are reliable, what else is new?

In 1961 Hondas finished 1st. 2nd, 3rd. 4th and 5th at the IoM in both 125 and 250. and went on to take both world titles.

The experts didn't say anything. Honda had done the impossible, so neatly and with such dispatch, that the press never got around to noticing what was being done, and how.

Here we are in 1979. There are two forces in road racing; Yamaha and Suzuki, with occasional efforts from Kawasaki. After experiments with Sixes and Eights and 12-speed gearboxes, the rules were tightened and Grand Prix bikes are pretty much alike. In the 500 class there are Yamahas and Suzukis, water-cooled four cylinder two-strokes, with multi-tube frames. Nobody has much of an advantage and everybody does it this way because that’s how its done.

Except that Honda has come back. With a racer that isn’t at all like the others.

Will history repeat? Will Honda roll up another umpty-six world titles?

Nobody knows.

What is clear is that this time we don't have to let the revolution go unreported.

Background. Honda’s return to GP racing is a result of corporate decisions and policy. We'll never see the minutes of those meetings, so we’ll have to guess at the reasons:

Honda is an engineering company, which isn’t the same as being a manufacturing company or even being a motorcycle company.

Honda likes to knock the world on its keister by doing clever and technical things.

Honda likes four-strokes. Always has.

The important people at Honda were bright young men 20 years ago. they worked on the racing team and they enjoyed it.

Most of all. Honda goes its own way. They do what they think should be done and the devil take how other people do it, or what other people say.

All of which adds up to the meeting that must have taken place several years ago, at which the VIPs decided to get back into racing, with a four-stroke 500.

We heard rumors first, about all sorts of odd tricks, about millions of dollars spent, breakthroughs achieved. Then the machine was shown to the press, but not ridden. Then it ran a few easy laps in public.

The real race debut, though, was scheduled for the British Grand Prix, at Silverstone.

Friday morning, Silverstone. First day of practice and qualifying.

Outside the paddock fence there’s a long, thin line. A row of people standing one behind the other, peering over shoulders and pointing cameras down a narrow alley between two motor homes. At the other end of the alley, the lights at the end of the tunnel as it were, Kenny Roberts and Kei Carruthers are in deep conversation.

Inside the paddock, in front of a pit wall, there’s a knot of people. They’re clustered in a tight circle. In the middle, smiling and bantering while posing with an endless supply of fans who are taking snapshots of each other, is Barry Sheene.

At the far end of pit row. behind the garage, is a huge striped tent. The largest crowd at the track is clumped outside the tent.

The tent flaps are tied shut. You can see nothing. Just the tent and the people.

Inside the tent is the Honda NR500. Every so often, but not often, during the day the mechanics will whip open the flaps. The NR (it stands for New Racer) will be rolled out of the tent, through the garage and onto the track, where riders Mick Grant or Takazumi Katayama will leap aboard and go for a lap or two. Then back down pit row, through the garage, into the tent and the flaps are secured before the mechanics begin whatever it is they’re doing in there.

In terms of popular interest, the order is Honda, Roberts, Sheene.

Not by accident. This is a concerted, deliberate thing, this technical dance of the seven veils. A hint here, a sketch there, a bit of hardware glimpsed for a second then tucked away, all this has been done to built interest, which it has done quite well. Honda will make the Grand Prix effort a major part of its future sales campaigns and they’ll create suspense by making us all guess.

Great stuff, if it works. But disaster if it doesn’t.

Meanwhile, though, you haven’t seen such peering into corners since Hollywood quit making movies about spies and secret agents. The Honda GP effort is being run by a subsidiary established just for this team, to be known as the Honda International Racing Co., or HIRCO for short.

HIRCO director is Gerald Davison, an experienced racing manager with Honda’s endurance team, as polite and cordial and hard to pin down as only an Englishman can be.

I had asked first to visit the race shop, thinking that surely a few days before the race they’d be willing to let me poke around, take notes and measure things.

Wrong. Members of the press are allowed no further than the ropes that close the garage to the public.

“Don’t go in the tent,” Davison says, “They’ll throw you out on your head.”

Honda is keeping its secrets to itself. How well this works was shown by another visitor inside the rope, outside the tent.

Keith Duckworth is the man who designed the Cosworth-Ford V-8, ruler of Formula One car racing. The engine was introduced 10 years ago. The week before the British GP, the one we’re at now I mean, a Cosworth-powered car won over the turbocharged and 12-cylinder GP cars by such a convincing margin that they filed formal protest. The Cosworth had to be oversize. It was impounded. And was declared legal.

Duckworth has credentials. He also has doubts. He’s on record as saying he doesn’t think a four-stroke can match a two-stroke on an equal basis. But here he is, inside the rope at the Honda garage. He’s got Shoichiro Irimajiri engaged in conversation. He’s throwing every leading question he can think of.

“If you’re using some sort of dual piston, you’ve got to have a yoked connecting rod, right?”

The hint of a tiny smile flicks across Irimajiri’s face. “Yes, if you used dual pistons, you’d have to have some sort of yoked connecting rod.”

He’s giving nothing away. Off to one side Davison is seething with resentment. Who is this car chap? Why is he bothering Irimajiri. who has work to do? “Case of the cat telling the lion how to catch mice,” he mutters to me.

And it might be. But when Irimajiri excuses himself, Vic Willoughby, technical editor of Motor Cycle Weekly and I scurry over to Duckworth. He may have found out something we don’t know. When Duckworth leaves, Willoughby and I are collared by two Japanese reporters. We may know something they don’t know.

Let’s review the rumors. One of our trusted pals in Japan, a man close to Honda’s racing efforts since those early days, wrote to tell us the GP engine was a narrow V-Four with six valves per cylinder.

A Dutch magazine published photos of a three-cam cylinder head for a square Four, or a Four with a vee so narrow one head could cover both banks. We’ve seen sketches of a head with rotary valves on top, where the camshafts usually live. A European reporter flew to Japan, was allowed to take pictures of the engine, all buttoned up, by the way and came home saying in print that the engine was a tandem-piston job, a V-Eight disguised as a V-Four in some manner that would meet the FIM limit of four cylinders.

None of this was invented. The people who reported it, believed it.

The answer is Honda’s system. When they made the decision to field a GP team with four-stroke power, they assembled a project team. The teams guys sat down at a big table and threw in all the ideas that came into their heads. No. I wasn't there. But that’s how they do things at Honda R&D. and there’s no reason to assume this project was different.

To a large extent Honda’s future is riding on this project. To pick the engine in the> drawing board stage would be foolish. What they did—I think—is pick the most likely engines and put their thoughts in metal, that is, build some prototypes and see how they ran.

I think there were at least three engines; the V-Four shown here, a square Four and perhaps the tandem-piston V-Four. There may also have been six-valve heads, and even rotary-valve heads, just as Honda had an opposed Six running around R&D three years ago, for the press to, uh, accidentally discover.

(Irimajiri refers to the various bits and glimpses reported earlier this year as “April Fool” engines. HIRCO enjoys this cloke-and-dagger game as much as the press does.)

Engine

Well. What do we actually know about the NR500 engine? In rough outline, it’s a V-Four, with the forward bank low and the banks at an included angle of 100°. Normal angle for a V-Four would be 60° or 90°, but making the angle .wider gives room for the carbs within the vee, just as the CX500 uses 80° to give room for the rider’s legs. Irimajiri says in neither case does moving 10° away from normal harm the engine or cause extra vibration.

Induction is public knowledge. R&D experimented with fuel injection but couldn’t get the mixture control required, so the NR appears here with four twinchoke carbs. Each cylinder gets one carb, each throat feeds an intake port, each intake port has two valves. Each cylinder has four exhaust valves, each valve gets its own port. The four little pipes become two, and the two join into one that joins the pipe from the other cylinder on that bank. There’s an exhaust pipe and muffler for each bank. Right, a muffler. The FIM has noise rules for racing bikes, but even though Honda got a waiver, 105 decibels instead of the 100 db for two-strokes, the four-strokes make more noise and the NR wears a full muffler on each pipe.

Each cylinder bank has two camshafts, driven by gears. Diagramming pictures of the engine indicates an included angle of about 65° for the valves, the inlets being more vertical than the exhausts for more downdraft.

The valves. Dazzling business here. Multiple valves are back in vogue, thanks to Honda, although Harley, Indian, Triumph and Rudge and many more used four-valves-per 50 or so years back.

The first reason is well known. Little valves can be opened and closed more quickly, with less spring pressure, than big valves can.

Next, engine power depends on breathing, a function of port area, valve timing and lift. You can get more little valves above a given piston bore than you can get big valves. (In car racing, by the way, four valve heads never went away.)

Here’s a new one, thanks to Keith Duckworth. High compression is a Good Thing. The higher the ratio, the more power.

But. The NR500 will rev to 18,000 rpm now, with 22,000 planned for later. A fourstroke has stronger power pulses than a two-stroke has, but it has fewer of them. You need power strokes for power, which is why the engine has incredible revs.

We are dealing with astronomical speeds for the columns of intake mix and exhaust gas, columns which are being started and stopped hundreds of times per second. This requires longer valve timing. A production four-stroke will use 270°, a racing engine will get close to 300°, this super-speed 500 has to have well beyond that.

Fine. Now picture this. With long valve timing, the valves must be open when the pistons are at top dead center. Have to be. They must have room, or they’ll hit the pistons. Duckworth says this is the reason the four-stroke won’t work, see, because if you leave room for open valves, you enlarge the combustion chamber. Right. You can’t get the compression ratio you need for power.

However. Actual maximum breathing is controlled by the area beneath the valve head, between the head and the valve seat. Due to geometry, lots of little valves give equal area here with less lift. Bingo. Less lift means less risk of hitting the piston tops, equals smaller combustion chambers, equals more power. As a bonus, less lift means you get max lift quicker, so you have more valve opening for the same timing.

That proves the value of all those valves. But how to gët all those valves into a combustion chamber?

Oval pistons and bores. That’s one rumor confirmed by Honda.

Oval pistons aren’t new; there were tuning kits for Triumphs built in the 20s with oval bores and pistons. The shape is mostly a function of the need to pack all those valves into the chamber. Two large valves or four smaller ones fit nicely above a round bore. Two rows of tiny valves, though, lend themselves to a trench-like chamber, above a bore shaped like an oval track; semi-circles at each end, with a rectangle between them.

This shouldn’t be as difficult as it first sounds. Along with its subsidiary R&D company, and the subsidiary racing companies, Honda has a wholly-owned outfit whose job is to make the machines with which Honda makes motorcycles, cars, etc. They do good work, like the series of automated devices that put crankshafts through 72 consecutive machining operations without human intervention. One assumes that building machine tools that finish off oval bores, and designing rings to work in said bores, is not beyond their skills.

Guessing again, the shape of the heads, cams, etc., indicates that the combustion chambers look like a pair of standard fourvalve chambers, that is, two paired intake opposite two paired exhausts, spark plug in the middle, next to the same thing. (See sketch.) This fits all the parts, and the twin plugs speed flame propagation within that long chamber. Ignition is transistorized battery and coils; no tricks visible there.

Big secret below the valves. Davison was happy to explain the carbs, the valves, and the camshafts.

. But during practice, I noticed something.

The exhaust note. It’s deep, muffled, throaty, heaps more pleasant to the earwell, okay, to my ear—than the two-strokes.

And the NR500 sounds like an inline four. Whrooom, rather than the pulsing thunder you get from all the other vee engines I’ve ever heard.

I mentioned this to Davison and asked, in all innocence, about the firing order.

Slam. Down came the shutters. Everything between the valves and the crank is top secret, he said, and quickly changed the subject.

Hm. Normal vee engines share crank throws, which puts the cylinders thus paired up on a staggered order, 60, 90, 80 or 100 degrees apart. Firing orders are on the basis of 90-270, and that’s why the pulsing.

But unless Honda has invented something in exhaust tuning unsuspected by me and the rest of the world, some way of tuning out the sound of the irregular beats, a smooth-sounding four has got to have a 180° firing order; a power pulse every half turn.

You could do it with this engine. The crankshaft is at right angles to the wheelbase. The oval bores make for a wide engine. The NR500 is much wider than any 250cc Twin you ever saw.

All those revs need a terribly strong crankshaft. Lots of main bearings, rollers in this case. Honda likes plain bearings, but they won’t do here.

That means a built-up crank. What you could do, and what I suspect has been done, is have an outboard main bearing, then a throw, a center bearing, another throw, and an inner bearing. Then, in the center, the power take-off, and on the other side three more mains and two more throws. Each piston gets its own throw and the throws are 90° apart; a points-of-thecompass arrangement. When the righthand side is at north and east, the lefthand side is at south and west.

It would also be entirely possible to have the separate throws spaced 80° and 100° apart so the V-Four would fire every 180°, not the 170° and 190° firing interval that would occur with a standard 90° crank in the 100°V-Four.

Not the usual thing. But it would give 180° firing, just like an inline Four, and there’s room for it. You’d also get one heck of a rocking couple with one side hitting top dead center at the northeast while the other hit BDC at southwest. But then I remembered, we’re not looking at a Harley or Ducati here, we’re dealing, if the marks on the engines are correct, with a stroke of 36mm. Call it an inch and a half. The rocking probably wouldn’t be as bad as the smooth power flow would be good.

Behind the crank is a jackshaft, with the water pump driven off its left end, and then the clutch. The gearbox has six speeds, all indirect, no ratios given. Chain drive, of course.

One can’t speak of the bore size, not in the standard way, but with a stroke of 36> mm and a limit of 500cc displacement, the piston area should be about 3463mm2, which would be equal to a round bore of 66.4mm. That would make the NR500 oversquare by a factor of 1.81 to 1.

What this all means is a matter of speculation. We know some facts, we can guess at others, we won’t know for sure until Honda is ready to unbutton the engine or file for the scores of patents they say they can get from the ideas they’ve used here.

In a more practical sense, if the Suzuki and Yamaha two-stroke Fours produce 125bhp, and because the lighter NR500 is slower than the rival two-strokes, we’d reckon the NR500 was developing 95 bhp at its introduction.

Chassis

No matter what becomes of the engine or anything else about the NR500, the chassis is a first, and the most important technical leap motorcycle racing has seen for years.

Monocoque. Lovely word. Sounds exotic and space-age at the same time. There are people who’d have you think monocoque means a one-piece body-fuel tanktail section, or that a large backbone of sheet metal, with engine hung below, is a monocoque.

Strickly speaking, they’re wrong. The world’s truest monocoque is an eggshell. A stressed skin. A skin strong enough to do all the work that a frame would otherwise do.

This comes most clearly from aircraft. Airplanes first were made from bundles of sticks. Then they covered the sticks with cloth. Then they made the sticks of metal, and covered them with metal and one day somebody reasoned that if you placed the sticks right, and fastened the skin to them right, you could use fewer sticks, or struts, by that time. And then, if the skin was even better, you could leave out the frame entirely.

They did it on airplanes, then on cars.

And motorcycles are still made from metal sticks. Big tubes in diamond pattern have given way to smaller tubes in the form of a cage around the engine (a space frame, in aircraft or motorcar terms) but still, bikes are a generation behind.

Until now. The NR500 is a true monocoque, welded-up alloy panels that form the fairing, the body sides, the backbone area. The shape is rather like a free-form ice cream cone, with the tip at the steering head and the open end at the back.

Into the open end slides the engine and gearbox, with swing arm attached. The engine and gearbox bolt to the sides of the monocoque, becoming a bulkhead, the frame for the skin.

Irimajiri, having performed like most innovators by doing what is obvious once it’s been done, says the monocoque has to be the future. Look on the road, he says, and you see fairings. On the track, likewise. If you are going to have a skin, for comfort or streamlining or weather protection anyway, why not let the skin do some work while it’s there?

The monocoque skin is useful for another area: cooling.

Water cooling is what made two-strokes work. The experts said two-strokes had no potential because they made heat along with power and the heat was more than the air could carry away, directly at least.

So entered radiators.

Now. A radiator won’t pass as much air as hits its surface. The tubes and fins are an obstruction. The car guys learned years ago that at speed, you can get away with a radiator intake one-third to one-fourth as large as the radiator’s cross section.

If you have a properly shaped intake and you can mount the radiator well behind it, with the air ducted to the fins.

Fine. Except that motorcycles are shorter than cars and there isn’t any room for sleek noses and ducting. You put the radiator in front, below the steering head and you accept increased aerodynamic drag as the price.

Honda doesn’t. The leading edge of a fairing is a positive pressure area. The sides, if you shape them right, can be negative pressure areas.

So the NR500 has two radiators, one on each side. The cooling intake is in the fairing center, below the steering head. The air is pushed in there and when the bike’s at speed, the air is pulled through the radiators by the windstream rushing past the sides. Kind of supercharged cooling, which brings less frontal area and better streamlining, i.e. more speed for the same power.

(There may still be problems with this. The NR appeared with covers on the radiators, ducting of some kind. The covers were removed for the first test sessions, and haven’t been used since.)

A less noticeable benefit from the monocoque is that the frame, so to speak, is outboard of the swing arm pivot. Honda has the output sprocket aligned with the pivot, easy to do with the mounting points outboard, so there’s no chain tension variation due to rear wheel travel.

The fuel tank rides atop the, uh, backbone portion of the monocoque and the seat and tail section—a sub-tub?—snugs down over the castings that carry the footpegs. This back section bears no extra weight and isn’t a stressed portion of the machine.

Suspension

On any other racing bike, the NR’s suspension would be headline news. Here, though, it’s merely less different than the rest of the machine is from other GP racers.

The front forks haveTrimajiri written all over them. One of his pet theories is that if you mount the axle with total inflexibility, you don’t have to worry as much about the tubes, sliders, triple clamps, etc.

The NR’s forks are telescopic, upside down. Common practice is to have the stanchion tubes bolted to the triple clamps on the steering head. Then the sliders, the cast pieces into which the stanchion tubes fit, carry the front axle.

Not on the NR. The lower tubes are the smaller ones, and they fit inside the tubes carried by the clamps. Weight is the reason here, perhaps, as this is a light bike and the lightness comes mostly from the monocoque. When sprung weight, controlled by the suspension, goes down and unsprung weight, like wheels and tires and brakes and hubs, remains the same, the suspension tends to be overcome. (That’s one of the reasons big bikes can be made to ride more comfortably than small bikes.) Thus, the smaller tubes are unsprung, the larger tubes are sprung.

But the lower tubes aren’t normal. They are castings, fancy ones, with large sections around the front axle. The axle threads inside both lower legs, completely surrounded and then clamped into place. Hard to imagine a more rigid system.

Next, the axle mounts behind the tubes. Totally different from the leading axles fitted by BMW years ago, then used on motocross machines and now coming back on mass-produced road bikes.

Irimajiri speaks good racetrack English, but to explain the trailing axle, he needed a diagram. Forces received by the front tire go to the axle, then up into the tubes. If the axle is in front, you get a bending, a twisting, which affects the springing and damping. The action goes up, while the> reaction into the frame is at an angle.

But. If you have the axle behind the tubes, the lines of action and reaction cross, so there’s less contortion.

Drawback here, at least to the observer, is that when the tubes are in front of the axle, they’re also .‘way in front of the steering post. Plus, on the NR the front brake calipers are in front, both of them. That's a lot of weight in front of the steering axis. By racing standards, as practiced by other designers, this would make for very heavy steering. The trailing axle also reduces trail, and the selfcentering force. Neither rider complained — nor would I expect them to, under the circumstances— but this does look odd.

The spring in front of the tubes is easier to understand. You can change it quickly and it frees space inside the slider and stanchion tube for the oil, air and valves, etc. Increase the volume and you get more scope for tuning.

Rear suspension is single shock, an idea used by other grand prix teams for several years now'. The NR has a normal swing arm, with a second smaller arm pivoting on it and running forward to the Showa spring/shock. The shock feeds into the rear-center-top of the monocoque. No details given but from the dials and such, the Showa unit can be adjusted for spring rate, pre-load and compression and rebound damping.

A small link runs from the rear of the gearbox up and back to the connection of the upper swing arm and the shock. This is simply a linkage point to keep the shock from moving up as it moved forward. A rigid upper arm, like that on the Yamaha monoshock, moves up. Honda wanted to keep the seat low, so they used a geometry control here.

Fairly normal rig. I thought to rag Irimajiri a bit and I asked why the suspension wasn’t as different as the rest of the NR, I mean, I sort of expected leading link forks, hubcenter steering, double trailing arm rear and so forth.

No, he said, in what seemed to be all seriousness, they had enough to do with the engine and the monocoque, so they used straightahead suspension in order to be able to dial in adjustments at the track.

Oh, I said, remembering those April Fool engines.

Brakes are disc, naturally, with holes drilled in the inner portions of the rotors and slots coming in from the circumferences. Looks like another way to get water oft’the surfaces in the wet and clean grit off the pads in the dry.

Dunlop supplies the tires, on 16-in. Comstar-style wheels. The smaller wheels lower the bike, of course. The Dunlops used at the race were much wider and lower than normal, the idea being that the smaller wheel means a shorter footprint, so you have to widen it to get the same contact patch.

A challenge, obviously, and the Dunlop people say they’ve tried 12 compounds, in 10 designs, during their development program with the NR.

Enough tech talk. What we saw in the NR500, as introduced at Silverstone, was a knockout of engineering insight, a daring attack on the status quo. the old revolutionaries back to knock all the experts on their tails again.

Informed guess work puts the NR’s power at 95 bhp. Gossip says the first version of the NR weighed 220 lb., but that after the initial tests and the beefing up of weak places, the bike hit the grid at 240 lb. or so. Sensational work, considering that the RG Suzuki and YZ Yamaha tip the scales at nearly 300 lb.

So what we also saw was an underdog.

There were other factors working here. It was very important to Honda, the men at the top I mean, to have this bike at this race. They said they’d do it. they needed it to be done.

Was the NR ready? Probably not. No race bike is every ready.

Further, Silverstone is a fast track, a power track. Earlier in the week, HIRCO rented Donington Park, a tight track. A handling track. Earlier this season Wi! Hartog on a works RG Suzuki set a 500cc lap record at Donington, of 1:15.8. Mick Grant lapped Donnington during the tests at 1:18.8. Not a shabby first time out.

Practice

Silverstone isn’t Donington.

The Honda riders are Mick Grant and Takazumi Katayama. Both are experienced. Grant has won countless superbike races. Katayama was 350 world champ in 1977. Both men are ranked in the top 20 road racer, by anybody’s score.

Below the level of Roberts and Sheene, though, there are perhaps ten good men. difficult to evaluate, and better than there are rides available. Honda’s entry into GP racing thus opened doors for two riders, and those lucky two turned out to be Grant and Katayama.

Why them? Nobody knows. Perhaps Honda made bids for Roberts. Sheene and Ferrari, but couldn’t afford the price. Perhaps they figured if they hired Roberts or Sheene and won, the headlines would say “SHEENE WINS” and forget about make of bike. Honda isn’t in this to make riders famous.

Whichever, Grant and Katayama are conscious that they have got jobs they couldn't hope to get, no matter why. This was an important occasion. Mr. Soichiro Honda himself even dropped by for the testing at Donington. although he didn’t stay for Silverstone.

Things did not go well. All the contenders began with times in the range of 1:32, 1:33. The NRs were off by several seconds, in the high 30s.

The others brought their times down as they worked out tires and suspension settings. The Hondas didn’t. They looked smooth, they sounded good, but again and again the bikes pulled off, into the pits, through the garage and into the tent. Sound of wrenches working at great speed.

Discouraging, for me. Never mind the results, the finishing order of the race. I've been around long enough to know that you seldom field a winner right from the start.

But the problem seemed to be the engine. Oil leaks. There was even one mechanic who came to the grid with the bike, and stood there clutching a giant roll of paper towels. Grant or Katayama would fire up and scoot away and he'd bend down with towels and mop up the oil.

That. I kept thinking, looks like a problem they should have been able to solve in the dyno room.

Kenny Roberts worked his way down to 1:29.81, the pole and the lap record. Sheene and Ferrari and Hartog weren't far behind. Meanwhile, the Hondas came in, got worked on, went out. came in.

“Power is the least of their problems,” an expert standing outside the garage told me, “it's the tires.”

No. The most of their problem was getting into the race. Katayama's best was 1:36.74. putting him 39th out of the 41 starters allowed. The cut was 1:37.2, and Grant’s best was 1:37.9.

Shortly before the start, Davison, looking grimmer than a barrel of hangmen, came ripping through the paddock on a pit bike. He slid to a stop outside the official’s building and burst through the door.

Made it. Thanks to other entrants falling off or having mechanical troubles, there was room on the grid. Grant was first alternate and he was allowed to start.

The Race

It was great. Stupendous. Best I ever saw.

Kenny Roberts is the best rider in the world. We knew that already, but watching him lap the field at Daytona or practice wheelies at Laguna Seca isn’t the same as watching Roberts against the world.

The other guys are good, too. At home, Kenny wins. In the world championship, he works for his wins.

During practice I went to the toughest corner on the circuit. Roberts came through knee down, front tire doing a jackhammer, skipping and stuttering while Roberts held it down, kept the front wheel in line by force of will.

After practice I commented. “Does the front tire always do that?”

“Oh, that isn’t the tire. There’s something not right in the monoshock and it’s feeding that back into the front wheel.”

Barry Sheene was a pleasant surprise. In the U.S., that is, reading what Sheene is supposed to have written, he comes off'as a lightweight, a wiseacre and a poor loser.

I think now, having watched him firsthand, that Sheene thinks the big talk is psychology. At close range he’s pleasant, good with the fans—and he’s a national hero, no question, world champion or not—and he surely can ride.

During practice his Suzuki looked like it was made of rubber. He came through the twisty bits with the bike in constant motion, squirming around, constantly moving off line. Sheene looked like a man wrestling an alligator, a sly and bad-tempered alligator at that. But he made it work.

Both teams did the right things overnight. Roberts and Carruthers dialed in whatever it took. Sheene's crew took a big chance and swapped rims and suspension settings at the same time. Into the field or into the fence, as they used to say at Indy.

At the start Hartog did a demon exit and came through in first place, pursued by Ferrari and Sheene, all bunched up. Roberts was in mid pack, covered in oil from a warm up lap leak, repaired on the grid. As the leaders dueled, Roberts caught up. then he and Sheene did a duet and ran off' from the rest.

Marvelous. They were closely matched, both bikes worked perfectly. And they trust each other. The contest was so even they raced with their heads, each man aware of what the other was doing. If Roberts was a foot wide here. Sheene would nip past, then reach behind him and make rude gestures, meaning “Did'ja see that? Try and catch me now!”

Then Sheene would leave an opening and Roberts would power past and communicate back. This went on to the last lap, with Kenny in the lead and Barry using a swing out and drive down that had him half a bike length, yes, after one complete race, in back.

What a race. The fans were so carried away that they swarmed onto the track, the better to honor their heros. Very un-English, the kind of thing one expects from a soccer crowd in Spain, but again, this was the sort of racing that causes even Englishmen to lose their reserve.

Indeed, one Englishman, to whom I hadn’t been introduced, congratulated me on Roberts’ behalf and I told him—and meant it—that I would have enjoyed it just as much if Sheene had won.

What? Oh, yeah, the Hondas.

Katayama came though in last place on the first lap, then passed some other bikes, then didn’t come ‘round again. Grant, I never saw. Turned out his engine got a terminal oil leak at the start. The oil dumped onto the rear tire and Grant went down, literally in flames.

Later in the program, during the Superbike race, 1 looked behind me while watching from a corner out on the track and there was Katayama. He really does like racing.

Or maybe he didn’t feel like hanging around the Honda tent.

Katayama is a rock singer in his spare time. Honest. He’s a cheerful man, affable, open to approaches.

“I missed you out there after the first laps,” I said. “What happened?”

“The engine began to misfire, then (with a smile and a shrug) I lost the front brakes.”

“What do you think of the bike?”

“Not enough horsepower.”

Katayama rides the way you'd expect a rock star to ride, lots of showmanship.

“The bike looked good, but you didn’t seem to be riding the way you usually do, you know, not hanging it out.”

Another smile and shrug. “Not enough horsepower.”

continued on page 93

continued from page 75

Time to sum up. To put the record in perspective, remember that after Honda knocked the other motorcycles out of the ring and walked away, figuratively dusting hands. Honda got into Grand Prix car racing.

They had a car that was different, they hired good drivers and spent piles of money and after several years the Honda GP car could win ... if the faster cars flung themselves into the trees or blew up.

Honda has on occasion done the impossible.

Honda has also failed.

After the British GP Mike Hailwood and Phil Read agreed on something, perhaps for the first time in their lives.

Honda has done it wrong, they both wrote. The way to win would be to build two-stroke fours, with tube frame, etc., and get down to racing and winning without all this technical mumbo jumbo.

They missed the point entirely. Winning isn’t everything. Honda wants to win by Honda's own standards, by doing it the wav Honda thinks it should be done.

More power to them, I say. Right, I am partisan in this. Racing is too important to be left to the racers.

How much of what Harley has learned from, the XR750 appears on this year’s XLCH?

How has the Suzuki RG500 made a better machine of the GS550?

Just what does the Yamaha TZ750 have to do with the XS850?

Now look at Honda. The CBX. the CB750, the CX500, even the XL250. they all sparkle with what Honda learned first time this happened.

The Honda NR500 didn't win its first race. Honda built a smoke-and-mirror machine. pumped us all up and then, right in front of 100.000 fans and world wide television. the NR500 fell down and went boom.

Let the verdict come from the man who was most in view when the NR500 failed: Mick Grant.

“I'm not disappointed. “They had to learn how far they have to g°“Now' they know.’’ El

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUpfront

December 1979 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1979 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

December 1979 -

Features

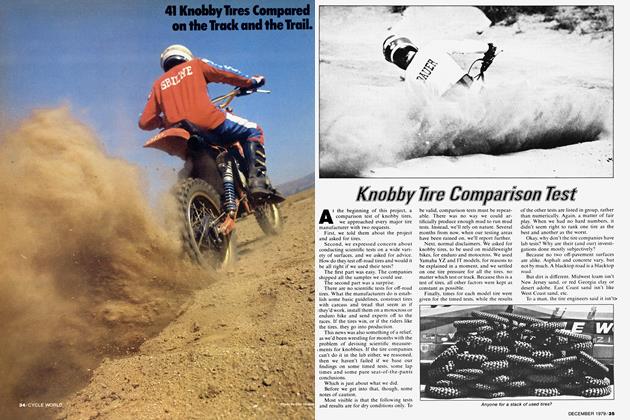

FeaturesKnobby Tire Comparison Test

December 1979 -

Features

FeaturesCold Storage

December 1979 By Glen Brinks -

Competitoin

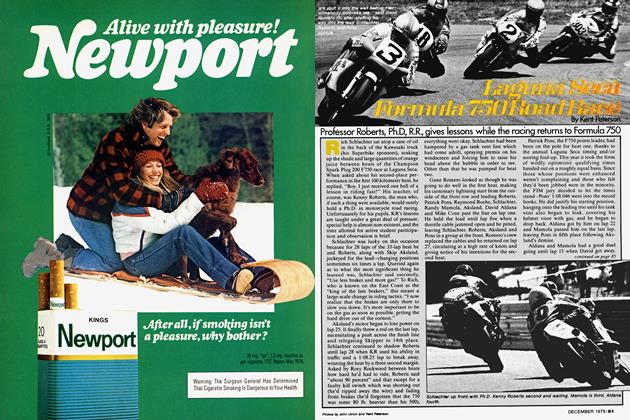

CompetitoinLaguna Seca Formula 750 Road Race

December 1979 By Kent Peterson