The Permanent Christmas Present

Doing It Right Is Better Than A Career Of Doing It Wrong

Allan Girdler

CHRISTMAS PRESENTS are made to be broken. As a father with 45 child/years experience I know presents are purchased with pleasopened with delight and used for the few days or hours it takes them to come apart. Even so, it hurt me as much as it hurt my 10-year-old son when he came trudging home the day after Christmas pushing—slowly—the best present he’s ever received.

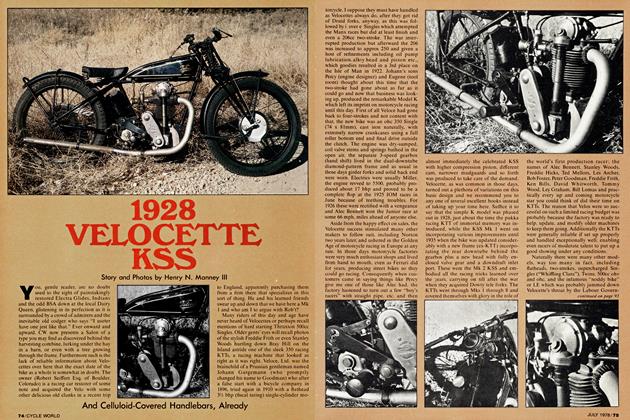

The present was a motorcycle, a real one, an Indian Junior Cross, just what he’d always wanted. His mother and I had a struggle with this, as we feel motorcycles are both expensive and potentially dangerous. We opted, finally and with some doubts, to take the positive approach. On Christmas morning there were three bikes under the tree: Honda SL70s for 14-year-old Kate and 13-year-old Scott and the Indian for John.

Operating the bikes was another problem. Not for the bigger boy, as he’d J^ad time on bikes borrowed from his ™als. At 8 a.m. Christmas morning he kicked his Honda into action, clicked into gear and headed for the hills behind our house, from which he’s since emerged only for meals and gasoline. The girl was less adept but she was also less eager. Kate viewed the motorcycle as a vehicle with which to visit friends in the neighborhood. She hummed away in the opposite direction, sedately and in second gear.

But John had had only a few minutes on bikes. He was eager. He knows about Ake Jonsson and Brad Lackey, about wheelies and power slides and all crossed up. But he didn’t know how to do it.

And I didn’t know how to teach him. Forklore is strong on fathers teaching sons the old way and the best way. Sometimes this works, usually when it’s Épmething father knows. About riding motorcycles I didn’t know enough. I can ride one, and I enjoy it, but I don’t know all the subtle techniques, and frankly, I am not that good a natural teacher. We set out to practice making starts, shifting gears, etc. He picked up some of the things he needed to know, albeit the instruction was along the lines of “The clutch! The clutch!” while he was trying to learn how to operate the clutch lever, the brake lever, the brake pedal, the gearshift and the throttle, all at once and all brand new to his experience.

Continued from page 103

Well. He headed for the hills. The second day he came slowly home, as mentioned. He was pushing slowly because the front tire was rubbing against the exhaust pipe. It was rubbing because the front forks were bent back. They were bent back because he had gone into a ditch, at speed.

He wasn’t hurt, not physically. Each new motorcycle had been accompanied by a Bell Star helmet, with instructions that use of motorcycle not preceded by use of helmet would be followed by confiscation of motorcycle. (If this was a family magazine I would take time Æ describe the trick of measuring a kid’s head without letting the kid know his or her head is being measured for a helmet needed for the motorcycle that’s going to be a surprise.)

John had been in over his head, so to speak. Cruising across a field he discovered a ditch directly ahead. He hadn’t known what to do, rather he knew what to do but didn’t have the time or skill to do it. So he crashed. The helmet paid for itself. Mom and dad paid for new forks. Problem: How to keep incidents like this from happening again, how could he learn what I couldn’t teach?

Solution: A school. By chance I went with a cyclist friend to Escape Country, a motorcycle park in Trabuco Canyon, Calif. At that time, Escape Country had a school for new riders (since discontinued), four hours, every Sunday morning Free. No charge. Perfect. S

The very next Sunday morning, then, John and his motorcycle were delivered to the school. I was impressed firstly by the instructor. Dave Young is an experienced rider and his regular job is directing the driver education program for a local school district. He thus knows how to ride and he knows how to teach, plus he understands kids.

The surprise of the day was that John was the lone pupil for the week. Incredible. This was just after Christmas. Surely hundreds of kids in the area had received bikes for Christmas. Surely the average father had no more skill or talent than I had. Surely there’s a need for competent instruction, I mean nobody is born knowing how to ride a motorcycle. (“I was,” the 13-year-old says.)

OK, one exception. But there must| be a need, there is a supply and few o^ the needy help themselves. Why not?

John helped himself ably. I retired, > figuring that pupil and teacher didn’t need me hovering over them with advice and criticism. As I left, though, John Wc^Jearning how to balance clutch and tli^Ptle, how to slip the clutch, when to shift and when not to shift, etc.

By lunchtime his progress was marked. There he was, threading his bike through a maze of rocks, feet up, using his weight to control the machine. He could go up hills and across ditches. He could shift up and down, could stop in a hurry. He was, in short, in control of his motorcycle.

We went to get a hot dog. I was happy. John wasn’t. He liked the teacher fine, but he was tired of practicing the same stuff, time after time. And then the real problem emerged.

Escape Country has two learner areas. John was in the being-taught area. Next to it and separated by a fence was the self-taught beginner area. John could see swarms of kids no older than him, riding around by themselves, on tfttir own. Did he have to be taught ,^Re the other kids—that most powerful of forces in a child’s life—got to just ride?

I am not a teacher but I know how to parent. “You,” I said, “will be taught until the teacher says you’ve learned all you can get from him.”

Back he went. To a surprise. For the afternoon session they moved into the larger practice area and John began to

work on the steeper hills, the deeper ditches, and with more speed. He made mistakes. Shifting from second to first for a hill he cranked in too much power and the bike went into the air. John turned loose and hit the ground running while the bike sailed away and down without him.

“That was the right thing to do,” the instructor said. “How did you know to do it?”

“I dunno,” said John, very pleased, “it just seemed like the right thing to do.”

He kept at it, faster and faster, shifting his weight, standing up, leaning back, all the time looking more and more sure of himself and the bike... enough. John had learned, or more accurately had been taught, how to ride his motorcycle.

John has the proper foundation. It was a gift, and it's a gift that will not break or wear out. It can't even be lost or forgotten. John knows now that the methods work. After he was turned loose, a graduate, he rode out into his peers, the kids who had been riding when he'd been learning.

They weren’t his peers. When John balanced through the mud holes, they fell over. When he crested the hills, they stalled.

Four hours of being shown how to do it right is better than a career of teaching yourself wrong. [o