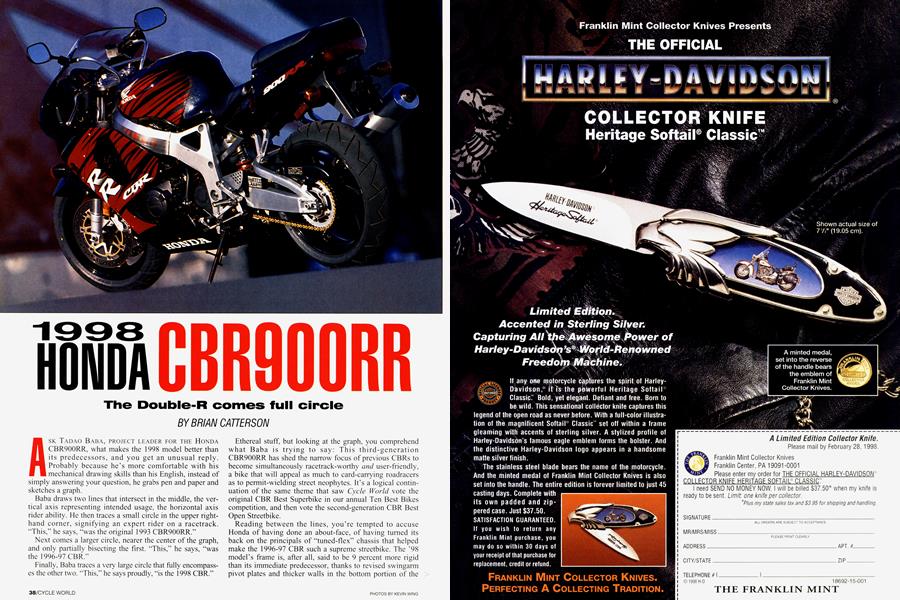

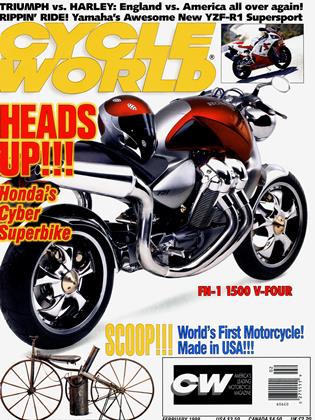

1998 HONDA CBR900RR

The Double-R comes full circle

BRIAN CATTERSON

ASK TADAO BABA, PROJECT LEADER FOR THE HONDA CBR900RR, what makes the 1998 model better than its predecessors, and you get an unusual reply. Probably because he’s more comfortable with his mechanical drawing skills than his English, instead of simply answering your question, he grabs pen and paper and sketches a graph.

Baba draws two lines that intersect in the middle, the vertical axis representing intended usage, the horizontal axis rider ability. He then traces a small circle in the upper righthand corner, signifying an expert rider on a racetrack. “This,” he says, “was the original 1993 CBR900RR.”

Next comes a larger circle, nearer the center of the graph, and only partially bisecting the first. “This,” he says, “was the 1996-97 CBR.”

Finally, Baba traces a very large circle that fully encompasses the other two. “This,” he says proudly, “is the 1998 CBR.”

Ethereal stuff, but looking at the graph, you comprehend what Baba is trying to say: This third-generation CBR900RR has shed the narrow focus of previous CBRs to become simultaneously racetrack-worthy and user-friendly, a bike that will appeal as much to card-carrying roadracers as to permit-wielding street neophytes. It’s a logical continuation of the same theme that saw Cycle World vote the original CBR Best Superbike in our annual Ten Best Bikes competition, and then vote the second-generation CBR Best Open Streetbike.

Reading between the lines, you’re tempted to accuse Honda of having done an about-face, of having turned its back on the principals of “tuned-flex” chassis that helped make the 1996-97 CBR such a supreme streetbike. The ’98 model’s frame is, after all, said to be 9 percent more rigid than its immediate predecessor, thanks to revised swingarm pivot plates and thicker walls in the bottom portion of the triple-box-section aluminum spars. Furthermore, that frame is mated to a new bridged, taperedbox-section aluminum swingarm that is 21 percent stiffer, and to new aluminum triple-clamps that splay the fork legs .4-inch farther apart for a 10 percent gain in rigidity there, too.

Baba quickly dismisses your accusations, however, explaining that while the latest CBR’s frame is indeed stiffer than that of the ’96-97 model, it is far less stiff than the ’93’s. The difference, he continues, is that his team now can pinpoint precisely where they want the chassis to flex-or not to flex, as the case may be.

But there’s more to the ’98’s chassis changes than increased rigidity. There’s also revised steering geometry meant to quell the front end’s tendency to dance in fast, bumpy corners. As Erion Racing has long done with its CBR900RR-based racebikes, the triple-clamps now feature .2-inch less offset, which yields a comparable increase in trail and thus stability. Ordinarily, reducing the offset also would shorten the wheelbase, but Baba & Company maintained the 55.1-inch status quo by moving the CBR’s steering head forward a tad. Subtle-but effective.

The engine, too, has been shrewdly upgraded. Visually unchanged, the liquid-cooled, 919cc, dohc inline-Four has had some 83 percent of its internal parts altered to decrease weight, reduce friction and/or increase durability. Most noteworthy improvements are the new aluminum-composite cylinder sleeves (said to weigh 21.3 ounces less than the steel sleeves they replace, yet provide better wear resistance) and the new eight-plate clutch (said to weigh 9.1 ounces less than the old 10-plate unit, with no loss of reliability). This painstaking attention to detail has yielded a claimed 123 horsepower and 65.8 foot-pounds of torque, both figures notable increases from past models.

Honda allowed the ‘98 CBR to meet the press at the new Las Vegas Motor Speedway in Nevada. With a number of ’97 models available for back-to-back comparisons, journalists spent the morning riding the new bike on the stock street tires before being treated to racing slicks in the afternoon.

Why slicks rather than the customary race-compound street tires? According to Dirk Vandenberg of Honda’s Product Evaluation Department, “We stiffened up the chassis this year to make it more race-worthy, so we’re happy to show you that on slicks.”

Happy, too, were the journalists who no longer had to worry about slippin’ and slidin’ on street tires-not that they needed to worry, because the stock Bridgestone BT56 radiais acquitted themselves quite well. More remarkably, the CBR displayed no ill effects after the Bridgestone slicks were spooned on during the lunch break. Where many sportbikes’ chassis would buckle under the additional traction afforded by full-on racing rubber, the CBR never faltered. Indeed, it positively railed, turning the double-right in Vegas’ infield into a single, skidpad-style sweeper, and providing unreal drives out of the two long, looping lefts that lead up onto the banking. Yet even with seemingly limitless traction, the CBR displayed exceptional cornering clearance, only nicking its footpegs on the tarmac.

Though the increased trail makes the CBR’s steering feel slightly heavier, it pays dividends when trail-braking into a corner, like you would when entering the infield from Vegas’ back straight. There, where the old bike felt as though its front tire was going to turn-in and unseat you at any moment, the new bike just asked for a little modulation on the front brake lever, thank you very much. Furthermore, in conjunction with stiffer fork springs, revised suspension damping rates and a less-progressive shock linkage, the increased trail gives the new bike markedly improved high-speed manners. This was apparent while making the violent transition onto the banking approaching the start/fmish line, where with the speedometer registering deep into triple digits, the old bike repeatedly shook its head in protest while the new one just shrugged it off.

With 3 additional horsepower on tap and a slightly wider-ratio gearbox (only third gear remains unchanged), the new bike feels quicker than the old one while requiring fewer shifts per lap. Accelerating down the front straight, you could just pin it in fifth gear, rather than having to snick it into sixth as the old bike required. Even so, the speedo indicates 165 mph as you reach for the brake lever to begin slowing for the second-gear chicane that follows. There, you finally decide that the larger, 12.2-inch brakes also are an improvement, though it took a few break-in sessions to convince you-it wasn’t until you really started pulling on the lever that you noticed a difference.

By day’s end, you’ve garnered an appreciation for the 1998 Honda CBR900RR, speculating that what it might give away to the stunning new Yamaha YZF-R1 and the revitalized Kawasaki ZX-9R in the performance stakes, it will more than make up for in allaround usability. And you, too, are beginning to believe in what Honda higher-ups call “Baba Magic.”

But as the desert sun sets behind the Vegas skyline and the neon of the Strip begins to reflect off the clouds, you have one last question: “Tell me, Baba-san, what does the future hold for the CBR900RR?”

Tadao Baba smiles, looks down at his graph, and replies, “Bigger circle.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue