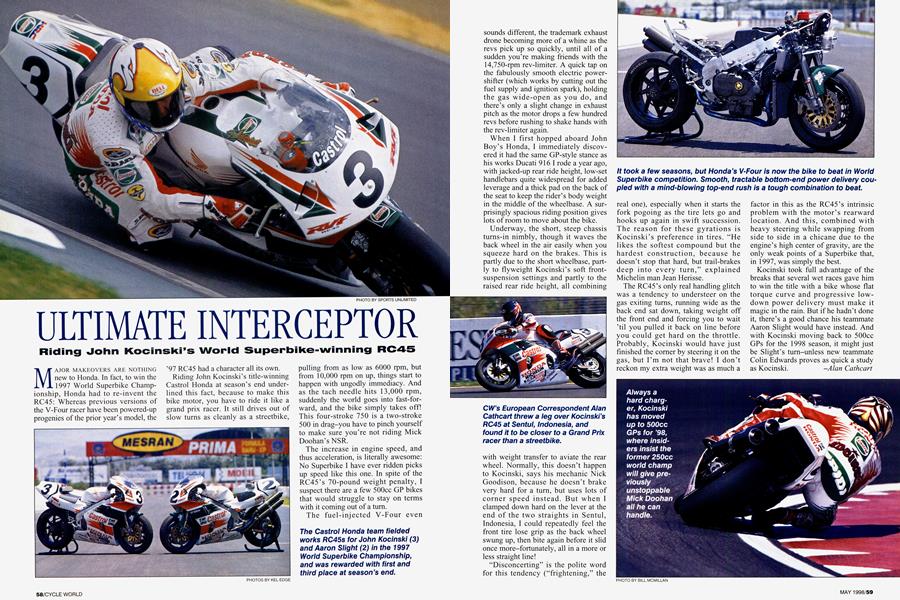

ULTIMATE INTERCEPTOR

Riding John Kocinski's World Superbike-winning RC45

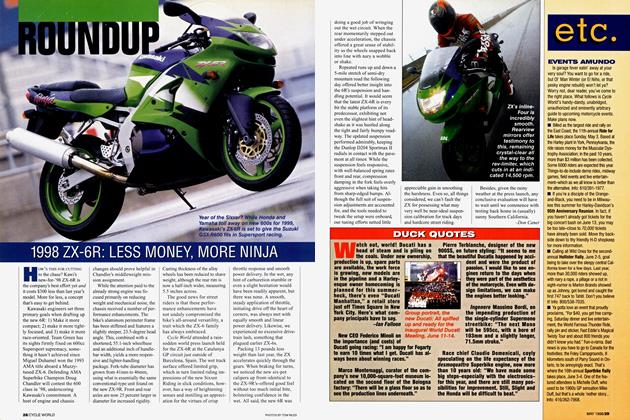

MAJOR MAKEOVERS ARE NOTHING new to Honda. In fact, to win the 1997 World Superbike Championship, Honda had to re-invent the RC45: Whereas previous versions of the V-Four racer have been powered-up progenies of the prior year’s model, the ’97 RC45 had a character all its own.

Riding John Kocinski’s title-winning Castrol Honda at season’s end underlined this fact, because to make this bike motor, you have to ride it like a grand prix racer. It still drives out of slow turns as cleanly as a streetbike, pulling from as low as 6000 rpm, but from 10,000 rpm on up, things start to happen with ungodly immediacy. And as the tach needle hits 13,000 rpm, suddenly the world goes into fast-forward, and the bike simply takes off! This four-stroke 750 is a two-stroke 500 in drag-you have to pinch yourself to make sure you’re not riding Mick Doohan’s NSR.

The increase in engine speed, and thus acceleration, is literally awesome: No Superbike I have ever ridden picks up speed like this one. In spite of the RC45’s 70-pound weight penalty, I suspect there are a few 500cc GP bikes that would struggle to stay on terms with it coming out of a turn.

The fuel-injected V-Four even

sounds different, the trademark exhaust drone becoming more of a whine as the revs pick up so quickly, until all of a sudden you’re making friends with the 14,750-rpm rev-limiter. A quick tap on the fabulously smooth electric powershifter (which works by cutting out the fuel supply and ignition spark), holding the gas wide-open as you do, and there’s only a slight change in exhaust pitch as the motor drops a few hundred revs before rushing to shake hands with the rev-limiter again.

When I first hopped aboard John Boy’s Honda, I immediately discovered it had the same GP-style stance as his works Ducati 916 1 rode a year ago, with jacked-up rear ride height, low-set handlebars quite widespread for added leverage and a thick pad on the back of the seat to keep the rider’s body weight in the middle of the wheelbase. A surprisingly spacious riding position gives lots of room to move about the bike.

Underway, the short, steep chassis turns-in nimbly, though it waves the back wheel in the air easily when you squeeze hard on the brakes. This is partly due to the short wheelbase, partly to flyweight Kocinski’s soft frontsuspension settings and partly to the raised rear ride height, all combining with weight transfer to aviate the rear wheel. Normally, this doesn’t happen to Kocinski, says his mechanic Nick Goodison, because he doesn’t brake very hard for a turn, but uses lots of corner speed instead. But when I clamped down hard on the lever at the end of the two straights in Sentul, Indonesia, I could repeatedly feel the front tire lose grip as the back wheel swung up, then bite again before it slid once more-fortunately, all in a more or less straight line!

“Disconcerting” is the polite word for this tendency (“frightening,” the real one), especially when it starts the fork pogoing as the tire lets go and hooks up again in swift succession. The reason for these gyrations is Kocinski’s preference in tires. “He likes the softest compound but the hardest construction, because he doesn’t stop that hard, but trail-brakes deep into every turn,” explained Michelin man Jean Herisse.

The RC45’s only real handling glitch was a tendency to understeer on the gas exiting turns, running wide as the back end sat down, taking weight off the front end and forcing you to wait ’til you pulled it back on line before you could get hard on the throttle. Probably, Kocinski would have just finished the comer by steering it on the gas, but I’m not that brave! I don’t reckon my extra weight was as much a factor in this as the RC45’s intrinsic problem with the motor’s rearward location. And this, combined with heavy steering while swapping from side to side in a chicane due to the engine’s high center of gravity, are the only weak points of a Superbike that, in 1997, was simply the best.

Kocinski took full advantage of the breaks that several wet races gave him to win the title with a bike whose flat torque curve and progressive lowdown power delivery must make it magic in the rain. But if he hadn’t done it, there’s a good chance his teammate Aaron Slight would have instead. And with Kocinski moving back to 500cc GPs for the 1998 season, it might just be Slight’s tum-unless new teammate Colin Edwards proves as quick a study as Kocinski. -Alan Cathcart