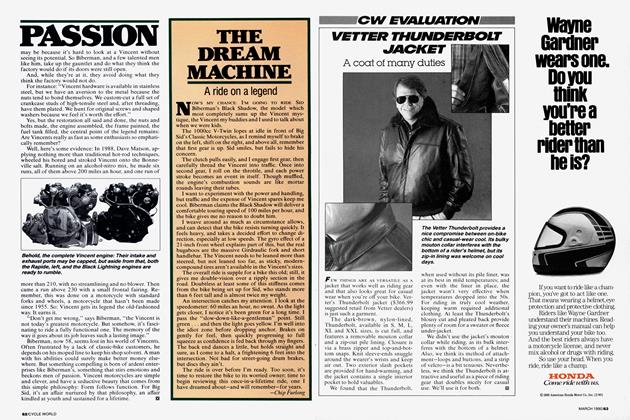

BIG SID'S PASSION

The Vincent may not be today’s ultimate motorcycle, but it’s all the motorcycle some people need

CHIP FURLONG

SIDNEY BIBERMAN IS A VERY LARGE ROMANTIC WHO speaks in rolling sentences-hushed and confidential one moment, rushed to full voice the next. He speaks. in his cultured, Southern voice, with the passion of one whose life has been pervaded by a single instrument.

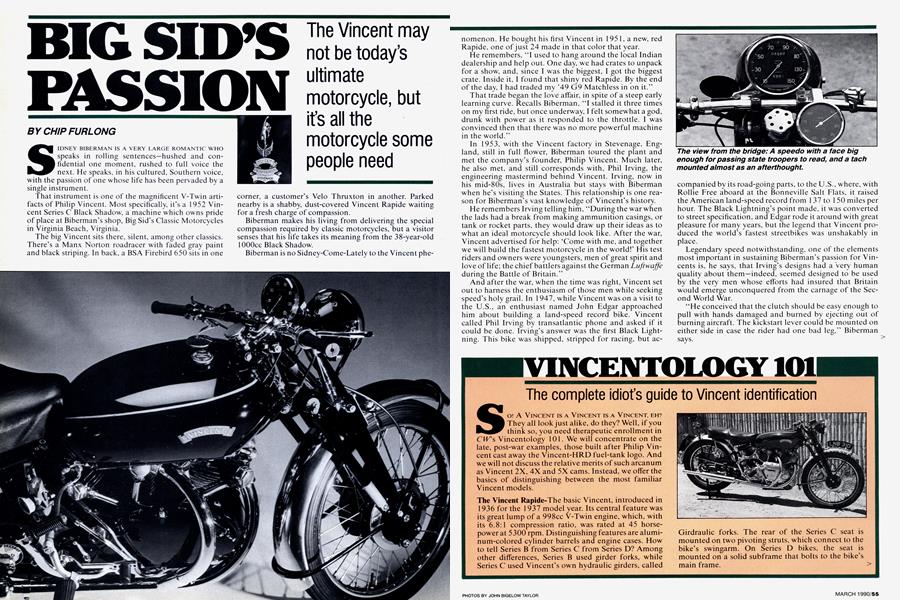

That instrument is one of the magnificent V-Twin artifacts of Philip Vincent. Most specifically, it’s a 1952 Vincent Series C Black Shadow, a machine which owns pride of place at Biberman’s shop. Big Sid’s Classic Motorcycles in Virginia Beach, Virginia.

The big Vincent sits there, silent, among other classics. There’s a Manx Norton roadracer with faded gray paint and black striping. In back, a BSA Firebird 650 sits in one corner, a customer’s Velo Thruxton in another. Parked nearby is a shabby, dust-covered Vincent Rapide waiting for a fresh charge of compassion.

Biberman makes his living from delivering the special compassion required by classic motorcycles, but a visitor senses that his life takes its meaning from the 38-year-old lOOOcc Black Shadow.

Biberman is no Sidney-Come-Lately to the Vincent phe-\ nomenon. He bought his first Vincent in 195 1, a new, red Rapide, one of just 24 made in that color that year.

He remembers, ‘T used to hang around the local Indian dealership and help out. One day, we had crates to unpack for a show, and, since I was the biggest, I got the biggest crate. Inside it, I found that shiny red Rapide. By the end of the day, I had traded my ’49 G9 Matchless in on it.”

That trade began the love affair, in spite of a steep early learning curve. Recalls Biberman, ‘T stalled it three times on my first ride, but once underway, I felt somewhat a god, drunk with power as it responded to the throttle. I was convinced then that there was no more powerful machine in the world.”

In 1953, with the Vincent factory in Stevenage, England, still in full flower, Biberman toured the plant and met the company’s founder, Philip Vincent. Much later, he also met, and still corresponds with, Phil Irving, the engineering mastermind behind Vincent. Irving, now in his mid-80s, lives in Australia but stays with Biberman when he’s visiting the States. This relationship is one reason for Biberman’s vast knowledge of Vincent’s history.

He remembers Irving telling him, “During the war when the lads had a break from making ammunition casings, or tank or rocket parts, they would draw up their ideas as to what an ideal motorcycle should look like. After the war, Vincent advertised for help: ‘Come with me, and together we will build the fastest motorcycle in the world!’ His test riders and owners were youngsters, men of great spirit and love of life; the chief battlers against the German Luftwaffe during the Battle of Britain.”

And after the war, when the time was right, Vincent set out to harness the enthusiasm of those men while seeking speed’s holy grail. In 1 947, while Vincent was on a visit to the U.S., an enthusiast named John Edgar approached him about building a land-speed record bike. Vincent called Phil Irving by transatlantic phone and asked if it could be done. Irving’s answer was the first Black Lightning. This bike was shipped, stripped for racing, but accompanied by its road-going parts, to the U.S., where, with Rollie Free aboard at the Bonneville Salt Flats, it raised the American land-speed record from 137 to 1 50 miles per hour. The Black Lightning’s point made, it was converted to street specification, and Edgar rode it around with great pleasure for many years, but the legend that Vincent produced the world’s fastest streetbikes was unshakably in place.

Legendary speed notwithstanding, one of the elements most important in sustaining Biberman’s passion for Vincents is, he says, that Irving's designs had a Very human quality about them—indeed, seemed designed to be used by the very men whose efforts had insured that Britain would emerge unconquered from the carnage of the Second World War.

“He conceived that the clutch should be easy enough to pull with hands damaged and burned by ejecting out of burning aircraft. The kickstart lever could be mounted on either side in case the rider had one bad leg.” Biberman says. Yet, for all that design excellence, the Vincent story came to an end in 1955. The company’s doors didn’t close because the firm built an inferior motorcycle. Rather, a fragile postwar economy simply put Vincent motorcycles out of reach of most enthusiasts.

“My original Rapide cost me $1125 in 1952.” remembers Biberman. “At that time, a Shadow cost $1340 and the Lightning $1700. In those days, you could buy a Triumph for $795, and a Matchless for $750.”

The fickle finger of fashion also played its part, as buyers warmed to mid-sized motorcycles and to the stylish vertical-Twin engines that powered them. But perhaps the most-significant nail in the Vincent coffin was the quality that had made the marque great. Almost handbuilt, the bikes were equipped with details like expensive, tapered roller bearings in the rear fork pivot, instead of the bushings used by other manufacturers. And nearly everything on the bike was adjustable to account for wear or personal preference. The company’s refusal to compromise its attitudes about quality reached a point, finally, where any profits remaining in motorcycle production were just squeezed out. And so the factory was closed, and the Vincent name relegated to the top of the classic,“They-Don’tBuild-’Em-Anymore,” heap.

But if Vincents are classics, they’re classics with a difference. One of the most important of those differences is that unlike the hoards of pedantically restored Triumphs and BSAs seen these days at Britbike meets, it’s rare to find a perfectly stock Vincent. Biberman theorizes that this may be because it’s hard to look at a Vincent without seeing its potential. So Biberman, and a few talented men like him, take up the gauntlet and do what they think the factory would do if its doors were still open.

And, while they’re at it, they avoid doing what they think the factory would not do.

For instance: “Vincent hardware is available in stainless steel, but we have an aversion to the metal because the nuts tend to bond themselves. We custom-cut a full set of crankcase studs of high-tensile steel and, after threading, have them plated. We hunt for original screws and shaped washers because we feel it’s worth the effort.”

Yes, but the restoration all said and done, the nuts and bolts made, the engine assembled, the frame painted, the fuel tank filled, the central point of the legend remains: Are Vincents really as fast as some enthusiasts so emphatically remember?

Well, here’s some evidence: In 1988, Dave Matson, applying nothing more than traditional hot-rod techniques, wheeled his bored and stroked Vincent onto the Bonneville salt. Running on an alcohol-nitro mix, he made six runs, all of them above 200 miles an hour, and one run of

more than 210, with no streamlining and no blower. Then came a run above 230 with a small frontal fairing. Remember, this was done on a motorcycle with standard forks and wheels, a motorcycle that hasn’t been made since 1955. So: Vincent gets its legend the old-fashioned way. It earns it.

“Don’t get me wrong,” says Biberman, “the Vincent is not today’s greatest motorcycle. But somehow, it’s fascinating to ride a fully functional one. The memory of the way it goes about its job leaves such a lasting image.”

Biberman, now 58, seems lost in his world of Vincents. Often frustrated by a lack of classic-bike customers, he depends on his moped line to keep his shop solvent. A man with his abilities could surely make better money elsewhere. But something compelling is born of ardent enterprises like Biberman’s, something that stirs emotions and beckons men of passion. Vincent motorcycles are simple and clever, and have a seductive beauty that comes from this simple philosophy: Form follows function. For Big Sid, it’s an affair nurtured by that philosophy, an affair kindled at youth and sustained for a lifetime. El

View Full Issue

View Full Issue