AT LARGE

When retro-tech flops

Steven L. Thompson

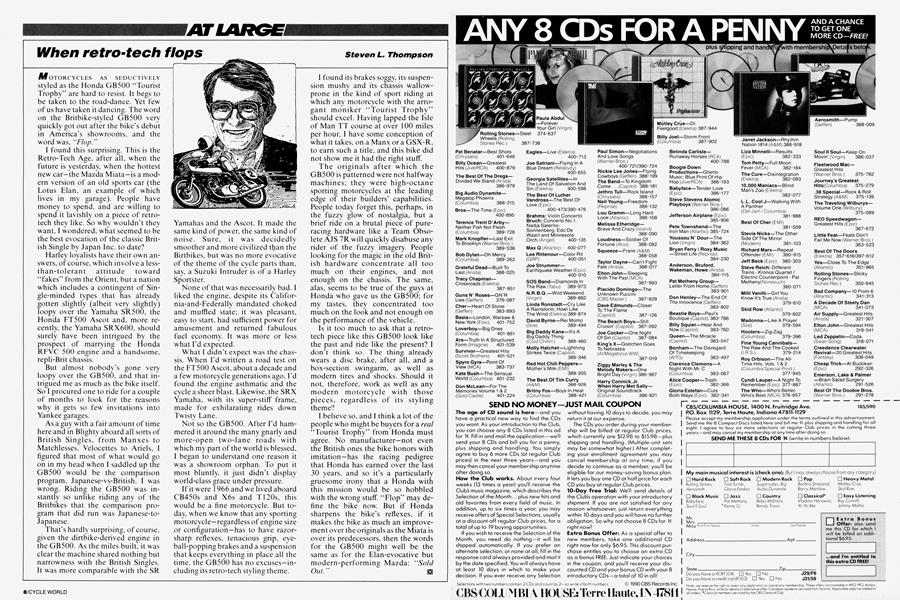

MOTORCYCLES AS SEDUCTIVELY styled as the Honda GB500 “Tourist Trophy” are hard to resist. It begs to be taken to the road-dance. Yet few of us have taken it dancing. The word on the Britbike-styled GB500 very quickly got out after the bike’s debut in America's showrooms, and the word was, “Flop.”

I found this surprising. This is the Retro-Tech Age, after all, when the future is yesterday, when the hottest new car—the Mazda Miata—is a modern version of an old sports car (the Lotus Elan, an example of which lives in my garage). People have money to spend, and are willing to spend it lavishly on a piece of retrotech they like. So why wouldn't they want, I wondered, what seemed to be the best evocation of the classic British Single by Japan Inc. to date?

Harley loyalists have their own answers, of course, which involve a lessthan-tolerant attitude toward “fakes” from the Orient, but a nation which includes a contingent of Single-minded types that has already gotten slightly (albeit very slightly) loopy over the Yamaha SR500, the Honda FT500 Ascot and. more recently, the Yamaha SRX600, should surely have been intrigued by the prospect of marrying the Honda RFVC 500 engine and a handsome, repli-Brit chassis.

But almost nobody’s gone very loopy over the GB500. and that intrigued me as much as the bike itself. So I procured one to ride for a couple of months to look for the reasons why it gets so few invitations into Yankee garages.

As a guy with a fair amount of time here and in Blighty aboard all sorts of British Singles, from Manxes to Matchlesses, Velocettes to Ariels, I figured that most of what would go on in my head when I saddled up the GB500 would be the comparison program, Japanese-vs-British. I was wrong. Riding the GB500 was instantly so unlike riding any of the Britbikes that the comparison program that did run was Japanese-toJapanese.

That’s hardly surprising, of course, given the dirtbike-derived engine in the GB500. As the miles built, it was clear the machine shared nothing but narrowness with the British Singles. It was more comparable with the SR Yamahas and the Ascot. It made the same kind of power, the same kind of noise. Sure, it was decidedly smoother and more civilized tl^an the Birtbikes, but was no more evocative of the theme of the cycle parts than, say, a Suzuki Intruder is of a Harley Sportster.

None of that was necessarily bad. I liked the engine, despite its California-and-Federally mandated choked and muffled state; it was pleasant, easy to start, had sufficient power for amusement and returned fabulous fuel economy. It was more or less what I'd expected.

What I didn’t expect was the chassis. When I'd written a road test on the FT500 Ascot, about a decade and a few motorcycle generations ago. I’d found the engine asthmatic and the cycle a sheer blast. Likewise, the SRX Yamaha, with its super-stiff frame, made for exhilarating rides down Twisty Lane.

Not so the GB500. After I’d hammered it around the many gnarly and more-open two-lane roads with which my part of the world is blessed, I began to understand one reason it was a showroom orphan. To put it most bluntly, it just didn’t display world-class grace under pressure.

If it were 1966 and we lived aboard CB450s and X6s and T120s, this would be a fine motorcycle. But today, when we know that any sporting motorcycle—regardless of engine size or configuration—has to have razorsharp reflexes, tenacious grip, eyeball-popping brakes and a suspension that keeps everything in place all the time, the GB500 has no excuses—including its retro-tech styling theme.

I found its brakes soggy, its suspension mushy and its chassis wallowprone in the kind of sport riding at which any motorcycle with the arrogant moniker “Tourist Trophy’’ should excel. Having lapped the Isle of Man TT course at over 100 miles per hour, I have some conception of what it takes, on a Manx or a GSX-R, to earn such a title, and this bike did not show me it had the right stuff.

The originals after which the GB500 is patterned were not halfway machines; they were high-octane sporting motorcycles at the leading edge of their builders’ capabilities. People today forget this, perhaps, in the fuzzy glow of nostalgia, but a brief ride on a brutal piece of pureracing hardware like a Team Obsolete AJS 7R will quickly disabuse any rider of the fuzzy imagery. People looking for the magic in the old British hardware concentrate all too much on their engines, and not enough on the chassis. The same, alas, seems to be true of the guys at Honda who gave us the GB500; for my tastes, they concentrated too much on the look and not enough on the performance of the vehicle.

Is it too much to ask that a retrotech piece like this GB500 look like the past and ride like the present? I don’t think so. The thing already wears a disc brake, after all, and a box-section swingarm, as well as modern tires and shocks. Should it not, therefore, work as well as any modern motorcycle with those pieces, regardless of its styling theme?

I believe so, and I think a lot of the people who might be buyers for a real “Tourist Trophy” from Honda must agree. No manufacturer—not even the British ones the bike honors with imitation—has the racing pedigree that Honda has earned over the last 30 years, and so it’s a particularly gruesome irony that a Honda with this mission would be so hobbled with the wrong stuff. “Flop” may define the bike now. But if Honda sharpens the bike's reflexes, if it makes the bike as much an improvement over the originals as the Miata is over its predecessors, then the words for the GB500 might well be the same as for the Elan-evocative but modern-performing Mazda: “Sold Out. [5]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

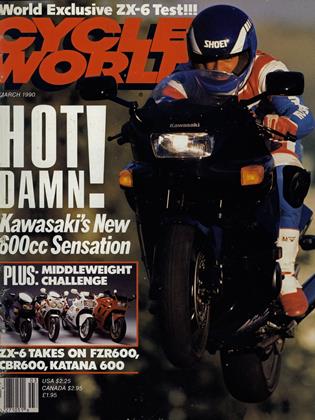

March 1990 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

March 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupRenaissance of Laverda

March 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupBuilding Your Own Beemer

March 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

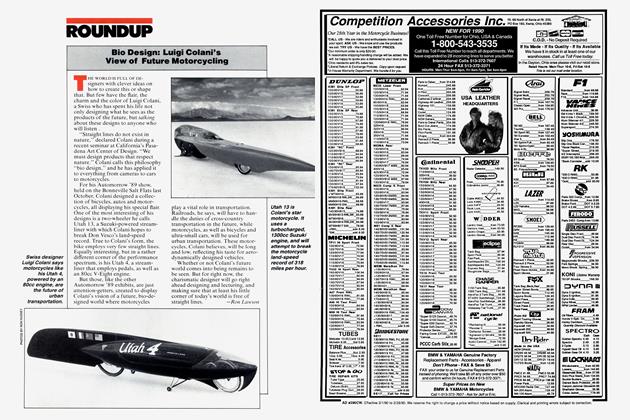

Roundup

RoundupBio Design: Luigi Colani's View of Future Motorcycling

March 1990 By Ron Lawson