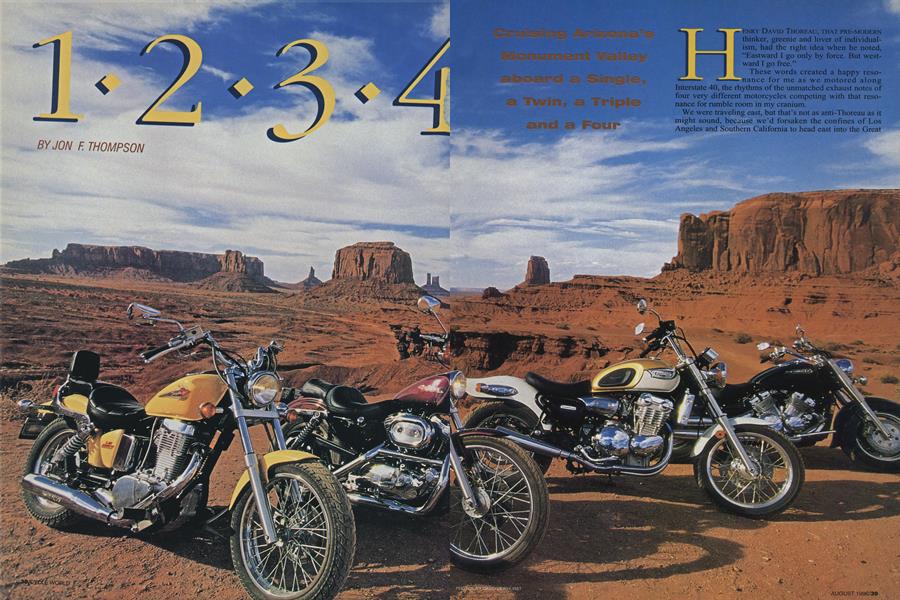

1·2·3·4

JON F. THOMPSON

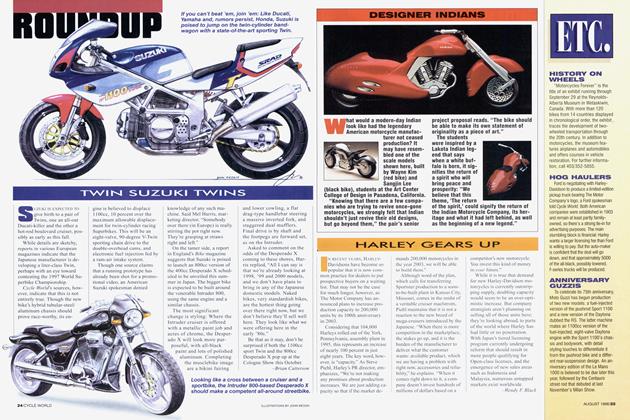

Cruising Arizona's Monument Valley aboard a Single, a Twin, a Triple and a Four

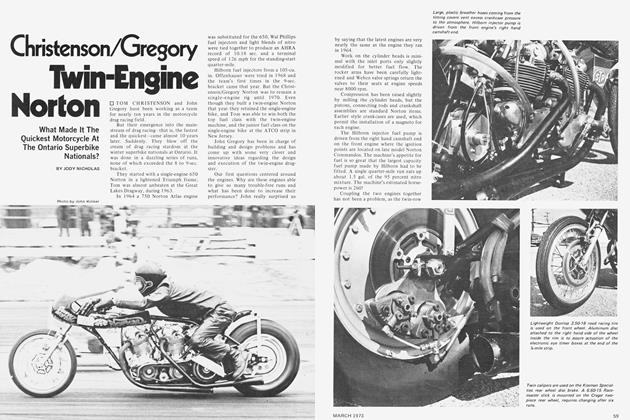

HENRY DAVID THOREAU, THAT PRE-MODERN thinker, greenie and lover of individualism, had the right idea when he noted, "Eastward I go only by force. But westward I go free." These words created a happy resonance for me as we motored along Interstate 40, the rhythms of the unmatched exhaust notes of four very different motorcycles competing with that resonance for rumble room in my cranium. We were traveling east, but that's not as anti-Thoreau as it might sound, because we'd forsaken the confines of Los Angeles and Southern California to head east into the Great American West, the wondrous space that has given rise to some of America’s most enduring and endearing mythologies—those encompassing cowboys, buffalo and Indians.

Cowboys, buffalo and Indians aren't really myths at all, of course. They’re real elements of the American experience, the bricks and mortar of a history that’s part of any American’s personal foundation. So it seemed appropriate that we explore the Great American West on motorcycles that echo and resonate with the American Experience.

They’re motorcycles my dad could appreciate. He’s 80, now, with poor eyesight and frail health, so while he remains keenly interested in motorcycles, he no longer rides. When he did ride, he was a Harley man who loved to cruise. Time hasn’t dampened his enthusiasm, especially for those curiously American machines we've learned to call cruisers.

Some suggest that such machines must be powered by VTwin engines. But the e are lots of other cruisers out there,

powered by alternative engines, that deserve our attention. From this variety, we chose three for this ride—a Suzuki Savage as our Single, a Triumph Adventurer as our Triple and a Yamaha Royal Star as our Tour—plus a Harley Sportster 1200 Custom as our token V-Twin.

Where to ride them? Indian Country seemed a terrific destination, the reservation of the Navajo Nation east of Flagstaff and north of Winslow, Arizona. It’s a place where time largely stands still, a place where a slow, speed-limit cruise—certainly out of the ordinary for Team CW, which mostly travels with afterburners and radar detectors lit—would reward us with vibrant color, scenic vistas and a heightened perspective of these four motorcycles.

“A Suzuki Savage? Are you kidding? That’s a toy, a g i’s motorcycle!”

Thus hooted my twentysomething artist pal K v Seeds when he learned of our plan. He wasn’t kinder to the Sportster, either.

Well, hell. Two pretty cool bikes, I thought. I was especially drawn to the Suzuki. Back about 470 years ago, in my last summer before I was shipped off to the boarding high school that would attempt to inculcate some civilization into this young hayseed, I was off at Camp Whitsett, a Boy Scouts of America summer camp in the High Sierras. I don't remember much about that week at camp, but 1 sure remember what I found in the garage upon arriving home. Leaning against a wall was a Matchless Single, a true California Desert Sled. It wasn’t to be touched, belonging, as it did, to one of the guys who worked on the farm where we all toiled. I never did ride that Matchless, but I’ve retained a wann spot for Big Singles, and at 652cc, the Savage qualifies.

S. me deal with the Harley. Early in my riding career I tri' , vard to trade off my ’48 Mustang Model 2 (see “The Ha^e f Yesterday,” CW, August, 1986) for a bright-red

chopped Harley 61-incher. Adventist boarding school, and the refining influences it promised, intervened. I’ve never forgotten that bike.

If I felt a natural affinity for the first two bikes, I was less sure about the other two. The Adventurer? A three-cylindered engine? Seemed wrong to me, as wrong as the Audi and Volvo Fives. As for the Royal Star-well, conceptually, anything that derives its powerplant from the V-Max can’t be all bad. Sure is big, though.

Just right, perhaps, for a big country. So it was that on a gem of a Wednesday morning, David Edwards, Don Canet, Eric Putter and I saddled up in Flagstaff and headed east, into The West. First stop, Winslow, Arizona, such a fine sight to see, looking for a girl, my lord, in a flatbed Ford. Winslow, which sits astride old Route 66, now is largely bypassed by the interstate. It sits, baked and forlorn in this high-elevation desert with very little going on, so frozen in time that I half expect to see Depression-era photographer Dorothea Lange working the town and its residents with her cameras.

I started the day aboard the Savage, and found that small though it is, it boasts a nicely stretched-out riding position. The engine seems badly in need of a pipe and a jet kit, though. It makes the bike the slowest of this bunch, with the most relaxed roll-on times. Still, the thrum of that single piston vibrates through me just as the rosewood-and-spruce soundbox of my Martin HD-28 does when I whack its strings with a flat-pick bluegrass lick. I approve of the little Savage, complete with its primitive suspension, for the same reason that I’d never part with my Martin-both have a simple integrity that I find immensely appealing.

We swap bikes and turn north, free of the tyranny and broken concrete of 1-40, and its cons and haul-ass trucks that threaten to either bust us or flatten us. The swap, each day’s ritual, is engineered so that at each change I gain a cylinder. So it’s the Sportster for this next leg.

Gaining a cylinder means that I also gain 548cc in engine capacity. This is a good thing, because it exchanges the Suzuki’s near-16-second quarter-mile for a time in the low 13s. Fun for blasting around town. Less fun and less useful, however, out on the wide straight stretches of the Southwest, where the Sporty’s very crude suspension has me wishing for a kidney belt, and its vibration so fuzzes the mirrors that at times I find myself wondering if the CW posse is still trailing me.

Then there’s this: The Suzuki may be the smallest bike of this quartet, but the Harley has the smallest riding position because of an odd handlebar bend and because its footpegs

are right under the rider, forcing him into an uncomfortable and, for a cruiser, extreme bend of the knees. I’ve little time to ponder this, though. We head north, dodging coyotes running across the deserted pavement of State Route 87 as we approach Second Mesa, a tiny reservation settlement.

We take in the scudding of the cumulus clouds that give the Southwest much of its visual signature. On sportbikes, we’d long ago have made Chinle, having cheated death and the highway patrol for the zillionth time. Instead, we’re still deep in the desert, deep in the 15-million-acre Navajo reservation, slowly approaching one of the best-known and best-preserved sets of Anasazi ruins anywhere, those of Canyon de Chelly, on bikes that allow us to relax and consider our surroundings.

Before we get to Chinle, there are more bike changes-at Second Mesa, I gain another cylinder as I jump onto the Triumph. This time, I lose 315cc, but that matters little. The Sportster is quicker through the quarter by about a 10th of a second, but on the highway the Triumph has better passing power. And it’s smooth, thanks to its gear-driven counterbalancer, though a high-frequency, low-amplitude buzz conspires to fuzz mirrors as badly as the Harley’s vibes do. Good seat, though, the best riding position of the bunch, and vastly better suspension than either the Suzuki or the Harley, able to soak up bumps the way my cats soak up tuna.

But, dang, who designed this thing? Is this the homeliest motorcycle you’ve ever seen, or what? We all agree, as we sit in Second Mesa’s only gas station sucking up buck-a-can soft drinks, that the Adventurer was styled with an ugly-stick. Bemused Navajos regard it, and us, from their battered pickups as they wait in line for water and gas while Edwards whines about no lunch and Canet whines about no comers. We all agree that John Bloor’s New Triumph has surrounded one of the world’s great motorcycle engines, filled with sound and fury, with a confusing and dizzying array of shapes and weird proportions. We’d rather ride it than look at it.

So that’s what we do, turning east onto State Route 264, into the teeth of a strong headwind. Even at 65 mph, we’re hanging onto our handlebars for dear life. Soon, our hands and fingers are begging for mercy, and so are the muscles in our forearms. No mercy is available, though, except from a trucker who flashes his lights to warn us of a radar cop skulking just ahead. We roll out and roll by at 55.

Where State Route 191 heads north for the last leg into Chinle we trade bikes again. I’m on the Royal Star-the “Yamacar,” 5-foot-6-inch Putter calls it. It’s my final cylinder. I’m up to four now, with a total of 1295cc, for a gain of 410cc. Great exhaust note; it reminds me of the sound of a hot-rod ’54 Olds that Keith Metcalf, my college roommate, once owned. Cool. Thing is, where’d all the horsepower go? Both the Sportster and Triumph are faster than the Yamaha. Nice smooth suspension to match its nice smooth styling, though, a kind of retro, deco look that makes me think it needed a role in the movie The Rocketeer. Also, the best mirrors of this quartet.

These thoughts in place, we gallop through Chinle and

into Canyon de Chelle where Mr. Photographer Dewhurst takes control of the trip to expose about 137 rolls of film, taking advatage of the desert afternoon’s wonderful light and the canyon’s incredible background.

More incredible backgrounds are in store for the next day, as we make

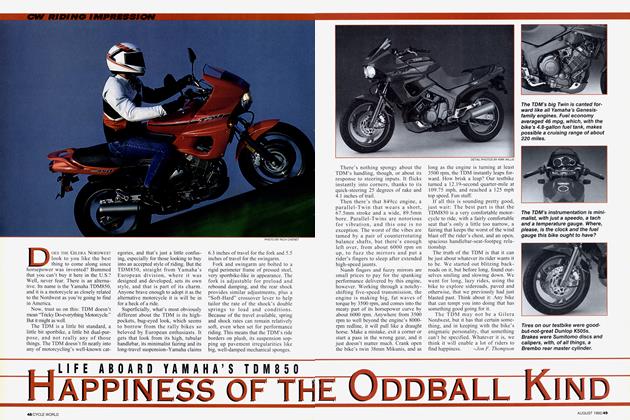

the short ride, swapping bikes four times again, to Monument Valley. The ride is short by design so Dewhurst will have time to do his work inside the valley itself, which is controlled by the Navajos. We’re sitting on John Ford Ridge while Dewhurst shoots 352 more rolls of film, and Edwards wonders, in jest, “Who let the Indians have all this great country, anyway?”

Actually, the Navajos have been on the Big Rez, as it’s called, since forever. Kicked out of the place by the Army in 1863 and deported to Ft. Sumner in New Mexico in a trip known as The Long Walk, they were allowed to return in 1868, the year U.S. Grant was elected president. Many still live according to traditional ways, keeping sheep, goats and cattle, though pickups have largely replaced horses, and many of their far-flung residences are served by electricity and satellite dishes.

No motorcycles, though, as far as we can see. No beer or wine anywhere on the reservation, either, much to the consternation of a pair of British tourists we encounter at dinner in Goulding’s Lodge, the one hotel that serves Monument Valley. Reluctantly, they make do with non-alcoholic cabernet. We make do with iced tea, Navajo fry bread and lamb stew. Eat like the locals, that’s us.

Our final day dawns. It’s Friday, and home beckons strongly. We make Dewhurst stay in his van with his timeeating cameras, but do swap bikes four times on the trip back to Flagstaff, jumping-off place to our separate trips back to the environs of Los Angeles. The trip is done into another 40-mile-per-hour headwind, and I’m reminded how much I appreciate fairings and windscreens. Which none of these bikes have, unfortunately.

If I were making this trip again, I’d change that. I’d not change much else. Not the selection of bikes, not the speeds and not the route, in spite of its lack of lunch spots and corners. This is empty country out here, filled with huge, long straightaways and lots of open sky. It’s the sort of place that enlarges our perspective of ourselves and our role on Earth. That’s one of the reasons I love it here.

The bikes? Cruisers, largely seen as city bikes, on a trip like this? Our consensus is that all could use better seats and better seating positions. All force their riders to sit less on their butts and more on their lower backs, with a huge and unnatural forward roll in each rider’s pelvis. Aside from that, we agree that the Adventurer has the best engine and seat, and the Savage has the best styling and proportion. Most important, we agree that a cruiser doesn’t have to be a V-Twin.

With that, we head west—Thoreau’s preferred directiontoward Los Angeles. The Navajos? They don’t care what we do, as long as we leave them alone. They and their forebears have been here for a thousand years, and to them, one day, one year, will be just like the last, and just like the next. Bikes like this have a lot in common with that refusal to be hurried, that reluctance to be caught up in bustle. That’s their charm. And that may be the most compelling reason to own one, however many cylinders it may have-one, two, three or four.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue