BSA IN A BOX

Would you bid $55,000 sight unseen for the last Gold Star? Nobody else would either—at least not yet.

JON F. THOMPSON

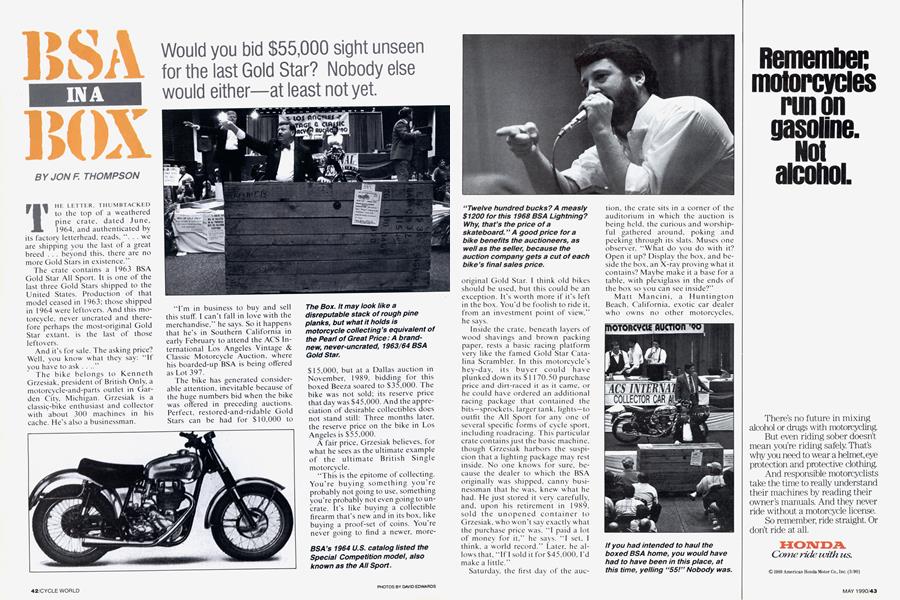

THE LETTER, THUMBTACKED to the top of a weathered pine crate, dated June, 1964, and authenticated by its factory letterhead, reads, “... we are shipping you the last of a great breed ... beyond this, there are no more Gold Stars in existence.”

The crate contains a 1963 BSA Gold Star All Sport. It is one of the last three Gold Stars shipped to the United States. Production of that model ceased in 1963; those shipped in 1964 were leftovers. And this motorcycle, never uncrated and therefore perhaps the most-original Gold Star extant, is the last of those leftovers.

And it’s for sale. The asking price? Well, you know what they say: “If you have to ask . . ..”

The bike belongs to Kenneth Grzesiak, president of British Only, a motorcycle-and-parts outlet in Garden City, Michigan. Grzesiak is a classic-bike enthusiast and collector with about 300 machines in his cache. He’s also a businessman.

“I'm in business to buy and sell this stuff. I can’t fall in love with the merchandise,” he says. So it happens that he’s in Southern California in early February to attend the ACS International Los Angeles Vintage & Classic Motorcycle Auction, where his boarded-up BSA is being offered as Lot 397.

The bike has generated considerable attention, inevitable because of the huge numbers bid when the bike was offered in preceding auctions. Perfect, restored-and-ridable Gold Stars can be had for $10,000 to $15,000, but at a Dallas auction in November, 1989, bidding for this boxed Beeza soared to $35,000. The bike was not sold; its reserve price that day was $45,000. And the appreciation of desirable collectibles does not stand still: Three months later, the reserve price on the bike in Los Angeles is $55,000.

A fair price, Grzesiak believes, for what he sees as the ultimate example of the ultimate British Single motorcycle.

“This is the epitome of collecting. You’re buying something you’re probably not going to use, something you’re probably not even going to uncrate. It’s like buying a collectible firearm that's new and in its box, like buying a proof-set of coins. You re never going to find a newer, moreoriginal Gold Star. I think old bikes should be used, but this could be an exception. It's worth more if it's left in the box. You'd be foolish to ride it, from an investment point of view,” he says.

Inside the crate, beneath layers of wood shavings and brown packing paper, rests a basic racing platform very like the famed Gold Star Catalina Scrambler. In this motorcycle’s hey-day, its buyer could have plunked down its $ l l 70.50 purchase price and dirt-raced it as it came, or he could have ordered an additional racing package that contained the bits—sprockets, larger tank, lights—to outfit the All Sport for any one of several specific forms of cycle sport, including roadracing. This particular crate contains just the basic machine, though Grzesiak harbors the suspicion that a lighting package may rest inside. No one knows for sure, because the dealer to which the BSA originally was shipped, canny businessman that he was, knew what he had. He just stored it very carefully, and, upon his retirement in 1989, sold the unopened container to Grzesiak, who won't say exactly what the purchase price was. “I paid a lot of money for it,” he says. “I set. I think, a world record.” Later, he allows that, “If I sold it for $45,000. I'd make a little.”

Saturday, the first day of the auction, the crate sits in a corner of the auditorium in which the auction is being held, the curious and worshipful gathered around, poking and peeking through its slats. Muses one observer, “What do you do with it? Open it up? Display the box, and beside the box, an X-ray proving what it contains? Maybe make it a base for a table, with plexiglass in the ends of the box so you can see inside?”

Matt Mancini, a Huntington Beach, California, exotic car dealer who owns no other motorcycles. knows exactly what he'd do with it. He'd hang onto the bike for a year and then resell it. Mancini is one of those interested when the dolly carrying Lot 397 finally is rolled to center stage on Sunday.

Observers only marginally interested in the bidding on an Excelsior Manxman, a Bimota SB4, an Indian Scout or a Norton International, turn quiet and move closer as the auctioneer starts the bidding for the Gold Star at $20.000.

“Gimme-the-money-gim me-themoney-I-got-30-now-I-got-35-I-got36-3 738-39-39-3 9-w ho's-gon nabid-40?” cries the tuxedo-clad barker.

And at $40,000. the bidding tapers off. The auction's ringmen. whose job it is to encourage the small knot of serious bidders that has formed front-and-center. succeed in bumping the number to $43,000— Mancini's final bid. He says later. “That's top dollar. In a year, it might be worth $50,000 or $60,000. But right now. 43 is it.”

Maybe. But it isn't good enough. Says the auctioneer, “Forty-three thousand dollars? Roll it off, roll it ofF. It’s gonna take $55,000 to buy that BSA today.”

“I'm not disappointed,” says Grzesiak later. “It didn't make its price. I wasn't sure it would. These (classic) motorcycles just haven't appreciated that much, though they seem to be doing so now. All these motorcycles have been undervalued for years.”

What Grzesiak is sure of is that it's only a matter of time before someone comes up with enough money to buy his BSA in a box, if only as an investment commodity. The auction-goer's catch phrase, “Buy 'em where you find ’em,” after all, certainly isn't going to change.

For now, Grzesiak's Gold Star will be returned to his Michigan shop.

“I've had over a hundred calls about this bike. Some people think they can buy it for $3500,” he notes. And a week after the auction, he adds, “I’ve got a buyer coming to see me. He was one of the bidders. He dropped out at $42.000. I know he wants the Gold Star.”

Grzesiak thinks fora moment, perhaps falling just a little in love with the merchandise, and then he says, “But I don't care if I sell it or not.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue