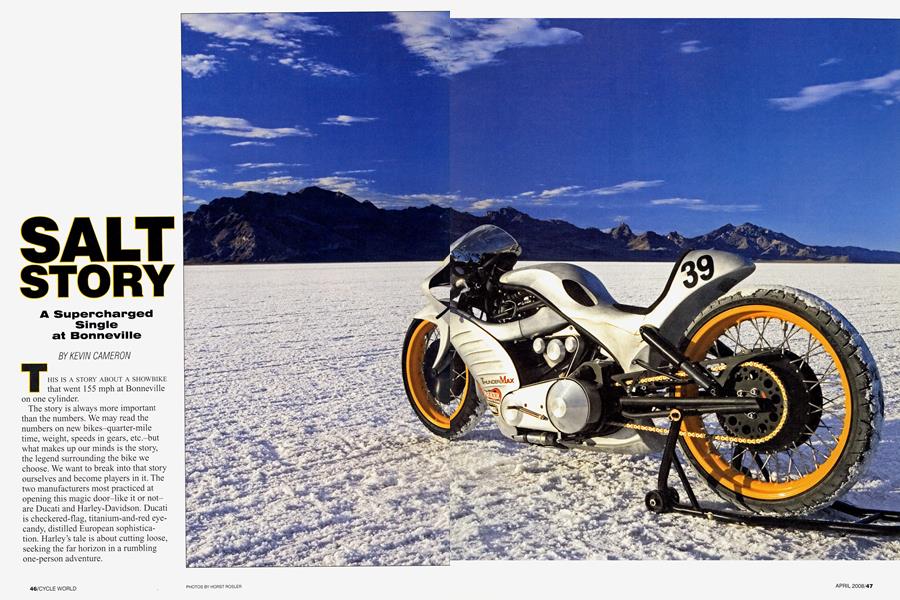

SALT STORY

A Supercharged Single at Bonneville

KEVIN CAMERON

THIS IS A STORY ABOUT A SHOWBIKE that went 155 mph at Bonneville on one cylinder.

The story is always more important than the numbers. We may read the numbers on new bikes-quarter-mile time, weight, speeds in gears, etc.-but what makes up our minds is the story, the legend surrounding the bike we choose. We want to break into that story ourselves and become players in it. The two manufacturers most practiced at opening this magic door-like it or not-are Ducati and Harley-Davidson. Ducati is checkered-flag, titanium-and-red eye-candy, distilled European sophistication. Harley’s tale is about cutting loose, seeking the far horizon in a rumbling one-person adventure.

Of course, a story too often told loses its punch. Time then softens it to the impact

to impact

level of an Alf Landon campaign button. Then what?

We have met 39-year-old Roger Goldammer before, a prize-winning custom-bike builder from British Columbia in western Canada.

“I manufacture cars, that’s what pays the bills,” he’ll tell you.

His shop is small-never more than five people work there. He finds his motorcycle themes in unusual places.

He likes Singles and builds his own, just as early American 500 and 350cc racers were built by plating over one cylinder of a big V-Twin. He likes board-trackers and he likes the grace of Norton’s single-cylinder Manx racers of 1935-63. Their inspiration is of the past but Goldammer wanted a new story to give life to the bike he planned to build. He decided to seek it at Bonneville.

Bonneville is tough for three reasons. Thirty seconds of full throttle melts engines at Daytona, but Bonneville is X times more arduous-an engine roasting-spit miles long. Pistons that win in drag racing punch through at the top of third gear at

Bonneville. Being the bed of an ancient lake, the Bonneville surface is moist or even wet salt, with grip only 40 percent that of dry pavement. The salt shorts out “sealed” electrical connectors and turns ignition boxes flaky. Look at the salt-encrusted tires in these photos! The sun hammers the people, drying them out, making them crabby, spoiling their judgment. I talked to one team who set a record with an Indian flathead their first year but couldn’t raise their speed in five years of trying. Everyone has a lot to learn on the salt. There are no experts-only students.

“This is the third Single I’ve built.

The second bike was influenced by the Manx Norton. I like the straight lines of the Manx-the thin seat, those frame tubes with the tank sitting on top of them,” Goldammer explains, and that influence is evident in this bike, too.

“This was a fun project, the kind of bike I love to build, a marriage of styles; nothing you’d ever build for a customer,” he says of the result, nicknamed “Goldmember.”

You can see that this is no conventional custom.

“I wanted to build for two arenas-custom and performance-because I’m kind of tired of blinged-out nauseating barges.”

Okay, how many Easy Rider clones can we genuinely appreciate, as we load our shopping carts with hundred-pound custom frames, tossing in those trick anodized belt pulleys that are sooo wide, and someone else’s earth-shaker big-inch engine, to build our conformist chariot to glory? Can Peter Fonda eternally steer that brakeless front wheel across the national landscape, peanut gas tank bulging with controlled substances, to the inevitable shotgun rendezvous? Granddad, tell me a new story! Yesterday’s cool/hot/rad is always at risk of becoming today’s yawn, dismissed as “whatever” by the oncoming generation as they look up from their game controllers.

Why a single cylinder? Dirtbikes made him a fan of Singles, and there were other attractive connections, such as classic roadracers and 1920s Singles like Harley’s “Peashooter,” built for the 21-inch (350cc) class.

Classic inspirations aside, what kind of power does this Single make?

“It hit 90 hp without nitrous on the dyno,” Goldammer reports. A commonly used figure for power-boosting with nitrous is 40 percent, which would take the power to 125 hp.

This is not a simple bike. It takes a lot of staring to figure out just what you’re looking at. As with his earlier Single, front suspension-spring and damper-is fitted inside the oversized steering head. That connects to the wheel via a girder fork. The girder’s bottom link is conventional. The top link connects to the hand-built equipment packaged inside the steering head. The rear shocks are extremely laid-down in the style of early long-travel MX bikes of 1973-4. The 21/20-inch wheel rims are painted-as they were in the faraway days before chromed steel and extruded aluminum. The chassis is conventional welded tubular steel. A large nitrous bottle mounts low in front of the engine’s cylinder.

The 965cc engine, based on Harley Big Twin architecture, is supercharged and intercooled. Bonneville being at 4300 feet above sea level means you lose more than 10 percent of normal air density. Boost is a hefty 22-23 psi. The large object where the rear cylinder should be is the belt-driven blower (its serpentine drive is on the left, designed to give adequate “wrap” to make a solid drive), and above it is the inlet to the charge air-cooler.

Compressing air in a supercharger raises its temperature, inviting detonation. Cooling it through an air-to-air heat exchanger allows more boost to safely be used without knock. The cooler, sitting at a 45-degree angle, leads to a pipe that serves the (originally) rear cylinder head’s front-mounted intake port, turning down over the top of the head just behind the steering head. It all fits. Head and barrel are by Mike Garrison of Engenuity. Cases are from Merch in Alberta. The crank is lightened.

For this transplanted rear head to work, Goldammer had to change the pushrod angles and needed special cams. A vendor wanted eight weeks to do the work. Too long.

“So I called them back and said if you don’t hear from me, what I’m going to do must have worked,” says Goldammer. “I took two cams, cored one out, turned the lobe off the other one, sleeved one onto the other and welded it. The welds broke and it bent the valves, but you learn. The first bike worked quite well. It made over 80 hp at the rear wheel. That’s from a Single-you know a new Harley Twin Cam makes maybe 65.”

What occupies the conventional fuel tank location is the housing around the engine’s intake intercooler. Its intake is the duct you see running back along the left side of the cylinder head, coming from its entry forward in the fairing. Hot cooling air from the intercooler exits through the opening at the rear of the dummy tank. The actual fuel tank is ahead of the rear wheel, under the front of the seat. Put things where there is room.

“The flaw with my first Single (also supercharged) was plenum volume,” Goldammer relates.

When British racing engineers tried to supercharge Singles for the Isle of Man TT in the late 1930s, they found that the blower couldn’t keep up with the single cylinder’s high-flow “gulp,” which sucked in the small intake volume, creating a once-per revolution vacuum that reduced power.

The answer was to place a large volume of charge near the intake port in a plenum chamber. Its modern analog is the sportbike’s airbox, which must for the same reasons be of many times the engine’s cylinder displacement. In Goldammer’s design, the charge air-cooler provides much of that needed plenum volume.

“The throttle body is 54mm-large even for a Twin, but with fuel-injection air velocity doesn’t mean a lot,” he says.

The engine and transmission are built on Harley FXR spacing. The primary toothbelt drive is, naturally, on the left.

Can those be drum brakes? No, Goldammer just likes their classic looks. The rear hub began as a 98-pound billet of solid 6061 aluminum, and most of it became chips. Working from a sketch, it was carved into the shape you see-with a functionally superior drilled disc brake concealed inside.

Visibility of features-as with classic steam locomotives-is important to Goldammer. He didn’t want to build a pure streamliner. There’s a lighting loom in the fairing nose so this bike can eventually be ridden on the street.

But first, Bonneville. They ran the bike on the dyno with 14 days to go until Speed Week. Not surprisingly, it had fuelinjection issues.

“There’s a blow-off valve to limit boost, to keep from blowing the intercooler off, but the pressure that built up cracked the manifold,” details Goldammer. “And we blew the blower belt off.”

More bugaboos. The air-fuel monitor was spiking to 17-to1, very lean compared with an ideal 12.5:1. >

"I decided, what the hell, I'll tune it at Bonneville," he s~ys.

These have been the famous last words of many a promising Bonneville effort.

The salt last summer was incredibly wet and slippery-“Like riding in slush,” says Goldammer. First run, at about 100 mph, he suddenly had no clutch and the bike downshifted itself.

Luckily, because the salt was so bad it acted like God’s own slipper clutch and Goldammer rode it out. Then all his gauges died from the vibration.

They spent the next few days fixing the clutch and the shifter.

Returning to that lean, 17-to-l fuel/air ratio reading, Goldammer reasoned, “How it feels is a primary experience; the gauge is an abstraction.” And it felt rich. He remapped the system sitting in a Wendover casino, leaning it out. Next morning it worked, the reading back inside the working range of the air-fuel sensor.

Mid-week, though, they still hadn’t tested the nitrous, a “wet system” with a separate pump for the nitrous-as opposed to vaporizing the liquid into gas. In a normally aspirated engine that might be set at 4 psi, but to get “past the boost” in this supercharged setup they started at 30 psi and in Goldammer’s less-than-clinical words, “made the jet real small.”

Finally ready to run, Goldammer played it safe and made a pass without hitting the nitrous button.

“We went ‘upstream’ (salt-speak for the outbound run) at 140 mph, but the return run ‘weathered out’,” he says referring to the rain that shut down the course. No return run within an hour, no official time.

“Next day, the final day of Speed Week, we test tried the nitrous on the access road, but it blew off the primary belt,” Goldammer says. “Friends helped, we leaned out the nitrous a couple of times, took a best guess on the setting and put on a new nitrous bottle.”

Ready for another run, the team got back in line, nerves not helped by the two streamliners that crashed ahead of them. Goldammer picks up the story: “Upstream, we went 142 mph. The return run was our last chance-we had two miles. One mile in, I hit a false neutral, but everything still looked okay so at about 30 mph I restarted the run. I kept it pinned, the engine shooting ducks the whole way. The speed was 154.8 mph with only one mile to accelerate, so it must have been still accelerating through the timer.”

I could feel the energy he’d put into this project build up and up as he told his tense story, and as he neared the final success, tiredness came into his voice. There were long pauses between sentences. Finally he stopped.

“You really feel alive,” he continued, summing up the Bonneville experience. “You’re there on a bike you built with your own hands. It had one mile on it when we loaded up for Bonneville.

“I love the starkness of Bonneville. We were so wellreceived there-it’s addictive, it’s a passionate group of people who are there simply in pursuit of performance. That’s sacred ground.”

What next for this supercharged showbike that took a detour to Utah and set a 147.438-mph class record?

“Now it comes apart,” Goldammer says. “It gets painted gold. It can run next year in its new clothes. The world really hasn’t seen this bike. It’s best when the look and the purpose can be one.”

Having a good story to tell doesn’t hurt, either. Ö