THE 1709 STORY

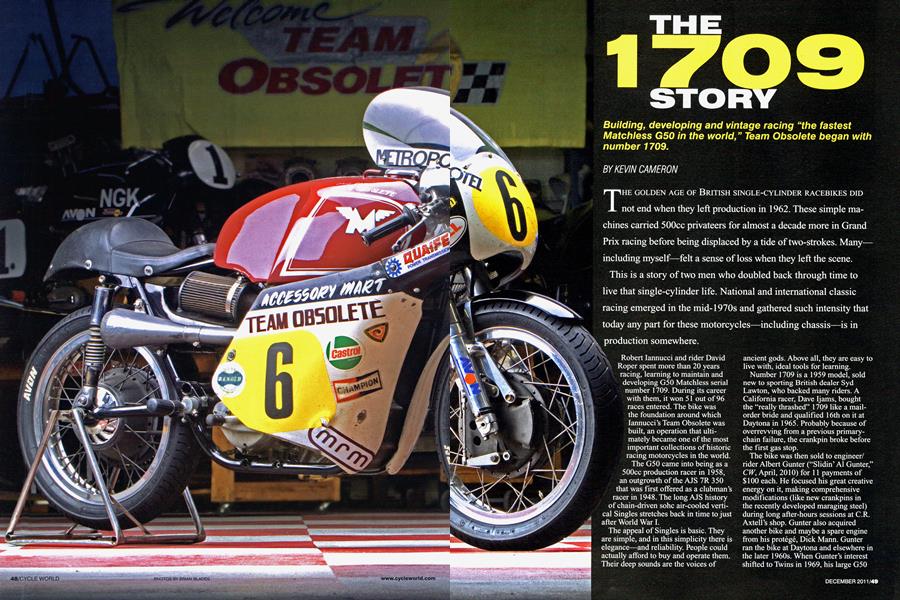

Building, developing and vintage racing “the fastest Matchless G50 in the world Team Obsolete began with number 1709.

KEVIN CAMERON

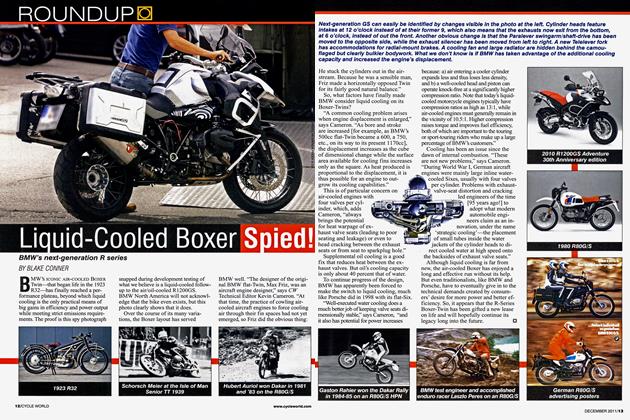

THE GOLDEN AGE OF BRITISH SINGLE-CYLINDER RACEBIKES DID not end when they left production in 1962. These simple machines carried 500cc privateers for almost a decade more in Grand Prix racing before being displaced by a tide of two-strokes. Many— including myself—felt a sense of loss when they left the scene. This is a story of two men who doubled back through time to live that single-cylinder life. National and international classic racing emerged in the mid-1970s and gathered such intensity that today any part for these motorcycles—including chassis—is in production somewhere.

Robert Iannucci and rider David Roper spent more than 20 years racing, learning to maintain and developing G50 Matchless serial number 1709. During its career with them, it won 51 out of 96 races entered. The bike was the foundation around which Iannucci’s Team Obsolete was built, an operation that ultimately became one of the most important collections of historic racing motorcycles in the world.

The G50 came into being as a 500cc production racer in 1958, an outgrowth of the AJS 7R 350 that was first offered as a clubman’s racer in 1948. The long AJS history of chain-driven sohc air-cooled vertical Singles stretches back in time to just after World War I.

The appeal of Singles is basic. They are simple, and in this simplicity there is elegance—and reliability. People could actually afford to buy and operate them. Their deep sounds are the voices of ancient gods. Above all, they are easy to live with, ideal tools for learning.

Number 1709 is a 1959 model, sold new to sporting British dealer Syd Lawton, who backed many riders. A California racer, Dave Ijams, bought the “really thrashed” 1709 like a mailorder bride and qualified 16th on it at Daytona in 1965. Probably because of overrevving from a previous primarychain failure, the crankpin broke before the first gas stop.

The bike was then sold to engineer/ rider Albert Gunter (“Slidin’ AÍ Gunter,” CW, April, 2010) for 11 payments of SI00 each. He focused his great creative energy on it, making comprehensive modifications (like new crankpins in the recently developed maraging steel) during long after-hours sessions at C.R. Axtell’s shop. Gunter also acquired another bike and maybe a spare engine from his protégé, Dick Mann. Gunter ran the bike at Daytona and elsewhere in the later 1960s. When Gunter’s interest shifted to Twins in 1969, his large G50 44holdings passed to one-time desert racer Bill Keen in Bakersfield. There they languished.

A young Robert lannucci languished, as well—isolated on a Caribbean island in the Peace Corps. His only solid link to the larger world was a magazine page featuring a G50 CSR. The CSR was the Honda RC30 of its time, a homologation special built by Matchless to give the G50 racing engine eligibility in AMA racing. The image moved into his head and settled there. After he returned to the U.S., he became an assistant district attorney in New York City and found himself spending hours on the phone and on the road, on a goal-less pilgrimage to track down G50s, engines, tanks and any parts. In 1975, he bought 1709 for $3000. Then [I bought] all the rest of the stuff—stacks and stacks of stuff. What a treasure trove,” said lannucci.

lannucci wasn’t an antiquarian—he wanted to race G50s. Because 1709’s engine was still unserviceable, he was glad to find a new G50 engine tucked away at Berliner (formerly the importer of AMC—Amalgamated Motor Cycles— the company that owned AJS, Matchless and Norton) in New Jersey. With that powerplant he rode 1709 a few times himself. After a year, he encountered Roper, an experienced rider who has always enjoyed racing for itself and not for the fair-weather friends it attracts. “David’s lines were graceful and he didn’t scrub rubber,” observed lannucci.

"His brakes didn't get as hot as other riders'. He was very even-tempered, analytical and easy on the bike." Another great seed came from Bob Hansen, who had run G50s in his Team Hansen racing efforts. "Two big things Bob did for us," recalls lannucci, "is that he gave us a list of all the people who'd bought G50 CSRs, and he had a fiber glass short-course tank with the vertical knee cutouts in the right place. I don't know whose legs the stock tank was made to fit, but it wasn't anyone I knew." Hansen also gave lannucci a copy of Jack Enimott's step-by-step 1964 "Book ♦of Engines” on the 7R and G50, plus a G50 manual.

“Pure gold,” said Iannucci with a smile. When you race a classic bike, all the problems it faced when it was stateof-the-art become your problems. The stock four-speed AMC gearbox had an ultra-close top-to-bottom ratio of 1.78:1. That was workable in a 224-mile Isle of Man race with a downhill push-start, but the shortness of modern classic races requires strong starts. That called for a low first gear. After some experience with other gearsets (some with big names but peculiar ratio steps), Iapnnucci had some six-speeds made up with a first gear low enough for starting, plus a properly spaced second, then the original four ratios. That made a good set. To make the work pay for itself, many gearboxes were built and sold into the classic-racing community. This would be the model for several of Team Obsolete’s developments.

The toothed-belt primary drive (far left) solved major reliability problems. The classic look—leather-covered seatback, gleaming alloy rims, a shapely fuel tank that fits human riders, low bars, a megaphone. It all happens in the cylinder head, topped by the magnesium cambox. Both fuel and oil tanks have flip-up caps.

“The appeal of Singles is basic. They are simple, and in this simplicity there is elegance—and reliability. People could actually afford to buy and operate them. Their deep sounds are the voices of ancient gods.”

The G50 powertrain is non-unitized— that is, gearboxes are mounted separately from the engine, driven by a dry clutch and an open primary chain lubricated by drip. “We tried everything to contain the oil necessary to keep that chain alive through a race,” Iannucci said. “And nothing worked.” The fix was the now-popular toothed-belt primary-drive conversion that, like Ducati cam drives, runs dry.

When I asked Iannucci what modifications were now in 1709, he said, “It’s basically Gunter’s engine.” This means cam, porting (including the exhaust port being raised up and to the right to get it out from under possible interference with the valve-spring seat), coil valve springs (hairpins were original) and twin ignition.

This surprised me because I remembered a long-ago Daytona race at which Iannucci had addressed 1709’s engine as if making a closing argument to a jury. He said he had given it more of everything it needed to make power— Gunter’s setup—yet it refused to deliver. What was it that eventually made the difference that brought the Gunter mods back to life? According to Iannucci, one part was long immersion in “the society of so many of the original guys—Jim Dour, Mike Crowther [formerly a cylinder-head specialist at Triumph’s Umberslade Hall research center], Dick Mann, Jim Cotherman, Tom Arter, Peter Williams, Bob Hansen, Udo Gietl.”

That was a living university in how engines actually work—squish, ignition, heat flow, parts durability. Another was the intensive learning that comes only from endless cycles of building up, seeing something break, and building up better than before. It all took time, like growing up takes time.

Big-end rod bearings were a problem. Original bearings were scarce, and Alpha (a long-time supplier of classic big-ends) was going through a “bad period.” People were revving the engines higher, with crankpin breakage becoming common even in the late 1950s. Iannucci therefore sought Mann’s help in implementing a solution.

“Dick came east, and he and Jim Dour [proprietor of Megacycle Cams and a former G50 racer] came up with a larger crankpin with a hardened, pressed-on bearing race, so the flywheels pressed right up to the race.” They also used an INA caged-needle assembly. Because its needles were much smaller than the quarter-inch rollers typical in the classic era, the rod big-end had to be sleeved down. This paralleled a similar move to INA big-ends at Harley-Davidson.

“A major weakness was the soft 3 5-tonne steel that AMC used for the flywheels,” said Iannucci. “People were revving these engines to 8400 rpm now but they were designed for 7200. The wheels were cracking.”

Both crankpin and mainshafts could work loose in the malleable steel. Team Obsolete’s oversized crankpin made it possible to revive such flywheels.

Later on, N.E.B. Engineering in England would make replacement 170mm flywheels of heat-treated stock that, with the improved big-end, have taken the crankshaft off the endangered list.

“We never had to replace a set of N.E.B. flywheels,” emphasized Iannucci. “Bob Newby says the engine is ‘sweeter’ with a titanium rod [pioneered by Jack Williams at AJS in 1955!], so we switched from Carrillo [steel] to titanium.

“When we started out, pistons were Hepolite—some cast, some forged,” continued Iannucci. “A slipper design with a one-inch pin was one variety.

But Hepolite stopped forging; Cosworth paid 5000 pounds for Hepolite’s forge. We bought about 100 Mahle pistons in various sizes.”

On another occasion they commissioned batches of Cosworth pistons—in four oversizes for the G50 and two for the 7R. Most experiments fail—they broke a piston across its ring lands at Windy Comer in the ’86 Classic Manx GP on the Isle of Man, revving to 8000. Another time the gearbox mainshaft broke at Creg-ny-Baa, leaving only the clutch pushrod comically supporting the clutch.

“What I remember is spending an awful lot of time [on the Island] fixing the bike in a damp little lock-up behind the Metropole hotel,” said Iannucci. “I went there for years and never did a lap of the Island—all I did was work. And we had to be up and running at 6 a.m. to be sure of getting a flying practice lap. I had to fix the rider, too—the cracked wrist bone from a crash.”

There was no ice to be found, save in the hotel bar—closed and locked up. With regret, they broke down a beautiful paneled door to get it. Back in the room,

Roper kept reflexively pulling the distressed hand out of the ice and Iannucci kept pushing it back in. The event medicos were skeptical at first but decided if Roper could do a pushup, he could ride. Racers are motivated human beings—he did the pushup. Then he won the 1984 Classic TT, setting the fastest lap at 97.21 mph—the only time an American had won a race there until Mark Miller’s victory in the 2009 all-electric TTXGP on the Motoczsyz El pc. It was also the only G50 to win a TT; stock G50s and 7Rs were reckoned to be best on short circuits, while the greater peak power of a Manx Norton was thought better suited to the Island.

Of the Manx GP, Iannucci said, “We never won it. But we came within 2.8 seconds in 1988.” (The “TT” was traditionally for professional racers, but the “Manx GP” was the clubmen’s TT.) Why not? “Ate a stone. While leading. That started us with air cleaners.” I could see a large, dirt-track-style air filter on 1709’s H/g-inch faux (meticulously made by Gunter) Amal GP carb. There was a matching relief in the oil tank—another Gunter production. Roper on 1709 and John Surtees on a most carefully prepared Manx Norton clashed in practice at the 1986 Circuit Paul Ricard classic event in the south of France-and Roper was the faster. Surtees, with grim determination, com pletely took his Norton apart and rebuilt it twice in an around-the-clock effort to find the missing speed. It wasn't there. "That may have been Surtees's last race ever," lannucci said.

After that, Classic Bike magazine titled its article about 1709 "Fastest G50 in the World." In 1988, Team Obsolete installed one of the latest Newby crankshafts, made with heat-treated wheels immune to the prob lems of the stock parts. They then won 500 Premier classic events all over the U.S. and in Canada, Australia and Europe. Eventually the team came to the end of the road with Lucas magnetos; Roper had lost 1000 revs off the top by the end of the 1992 IOM event. Professor Charles Falco has made a study of mag netos and says they are "lifed" for about 12 years. On that basis, G50 mags had overshot their flavor peak years earlier.

"We went to Blue Bell, Pennsylvania," Robert said, enjoying the irony of the nursery-rhyme name, "to Vertex. They started with a four-cylinder unit, elimi nated the distributor and cap to make a wasted-spark, 360-degree system." Because the Vertex is round, the G50's flat magneto platform had to be fly-cut, but the installation was straightforward. The team came to understand squish, the process in which the piston is brought nearly into contact with the head at TDC, forcing the mixture caught between into the open part of the cham ber in the form of turbulence-generating jets that accelerate combustion. They found they could reduce squish clear ance to .030-inch, thanks to the rigidity of the N.E.B. crank. With squish turbulence, timing for best power could be retarded, and that shortened the time during which cornbustion heat was lost into piston and head. More power. Cooler-running parts tolerate more compression without knock. More power again. Little by little, they found they could adopt the details of Gunter’s setup. It was all working together. Because the use of squish requires imaginative and accurate machining, the team was fortunate to have the help of “Frenchie”—the late Albert Arnaud, who had been an experimental machinist at Bendix.

"In 1992, we took 1709 to the classic race at the Mosport [Ontario, Canada] World Superbike weekend. Yvon Duhamel's time on that G50 [he was then 51] would have put him ahead of one-third of the Superbike grid."

But it was important not to go too far: “Too much compression is a problem,” Iannucci related. “Dick Mann said you mustn’t be greedy with compression.” They eventually settled on 11.2:1 for the G50.

“We never got into changing valve angles in the head or different bore and stroke. When the others began [doing those things], we were getting out. They were,” pausing as he smiled at what he was about to say, “outdistancing the parameters of my interest.”

By going to bigger bore and shorter stroke (stock is 90.0 x 78.0mm), with flatter, faster-burning combustion chambers, competitors were seeking to continue development. Right or wrong, it’s what racers do.

While 1709 was the focus of the team’s racing, Iannucci was also an impresario of classic racing in general, producing Giacomo Agostini on a late MV Agusta at one classic event, Jim Redman on a Honda Six at another and Dave Roper on a Benelli Four somewhere else—all over the world.

All this activity required a whirlwind of negotiating, preparations, packings and unpackings, carnet protection from zealous customs officials, all while attended by a cast, if not of thousands, then at least of enough people to require continuous and effective diplomacy. There is so much history and rare racing machinery in Team Obsolete’s Brooklyn headquarters that it is overwhelming.

Today, people pay large sums for the elements of classic racing, but 1709’s rear wheel came from a Minnesota scrapyard for $70, and the 210mm Fontana drum brake on the front (this was Roper’s favorite, although they had tried bigger) came from Hansen for not much more. All those phone calls created an effective “parts department” at a time when prices had not yet shot up.

Does the “obsolete” in Team Obsolete really have any meaning? Racing is about speed, no matter what name you tack in front of it. Fast is fast: “In 1992, we took 1709 to the classic race at the Mosport [Ontario, Canada] World Superbike weekend. Yvon Duhamel’s time on that G50 [he was then 51] would have put him ahead of one-third of the Superbike grid.”

Not bad for an “obsolete” old racebike. n

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

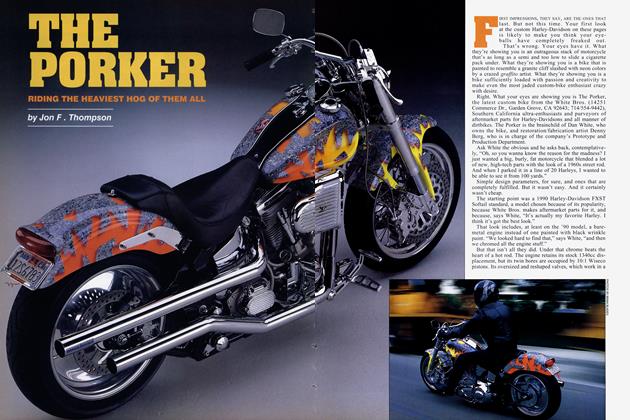

Up Front

Up FrontHome At Last

DECEMBER 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

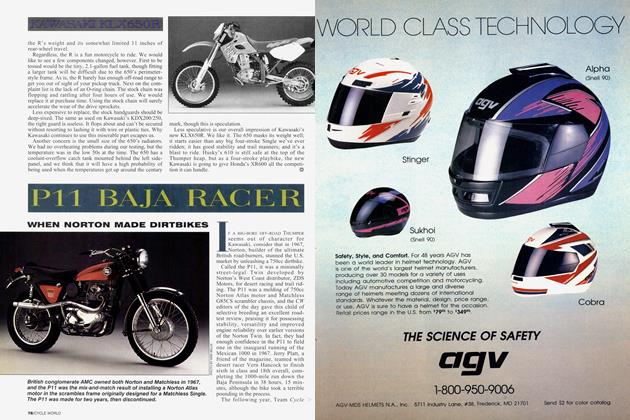

RoundupLiquid-Cooled Boxer Spied!

DECEMBER 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

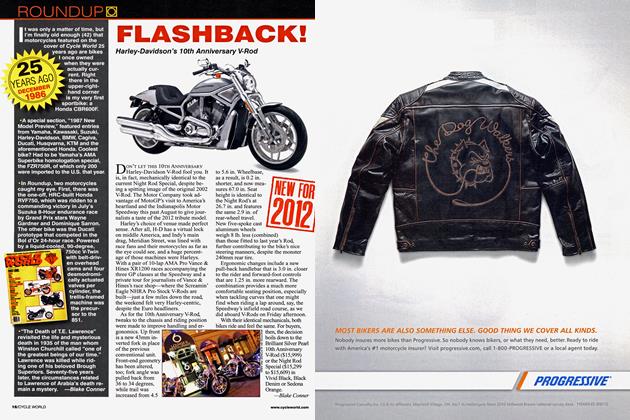

Roundup25 Years Ago December 1986

DECEMBER 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

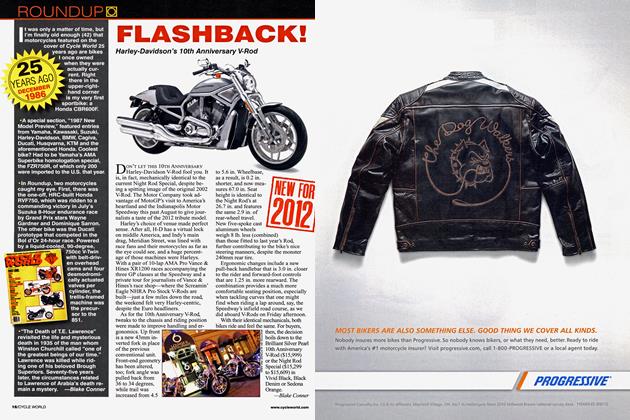

RoundupFlash Back!

DECEMBER 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupElena Myers Makes Motogp Debut At Indianapolis

DECEMBER 2011 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupDucati Streetfighter 848 And Diavel Amg

DECEMBER 2011 By Blake Conner