Grand Plan

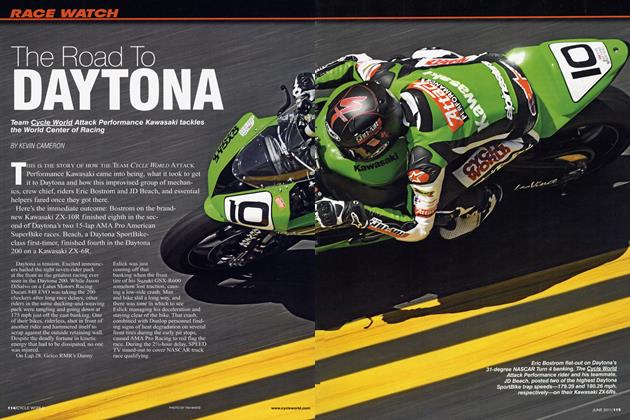

RACE WATCH

KEVIN CAMERON

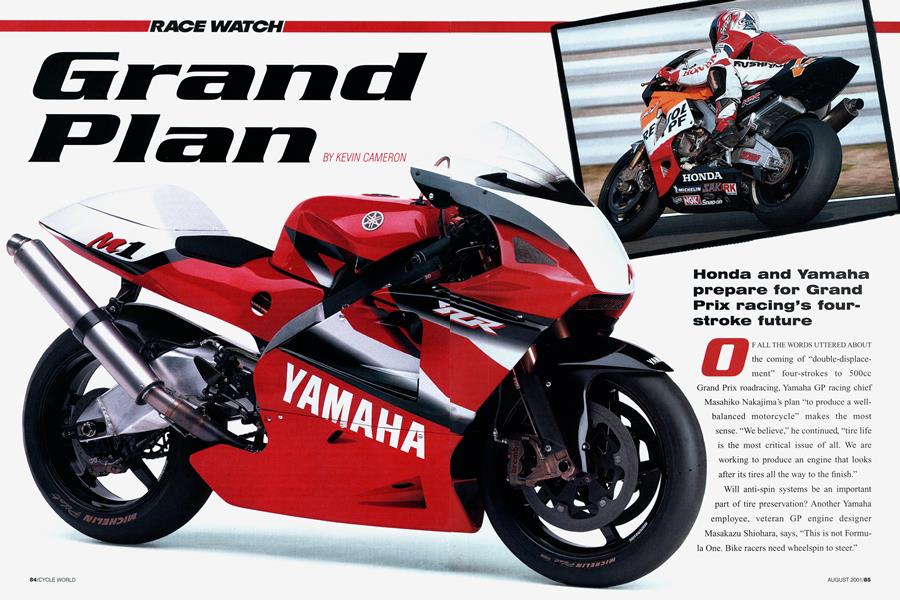

Honda and Yamaha prepare for Grand Prix racing’s four-stroke future

OF ALL THE WORDS UTTERED ABOUT the coming of “double-displacement” four-strokes to 500cc Grand Prix roadracing, Yamaha GP racing chief Masahiko Nakajima’s plan “to produce a well-balanced motorcycle” makes the most sense. “We believe,” he continued, “tire life is the most critical issue of all. We are working to produce an engine that looks after its tires all the way to the finish.” Will anti-spin systems be an important part of tire preservation? Another Yamaha employee, veteran GP engine designer Masakazu Shiohara, says, “This is not Formula One. Bike racers need wheelspin to steer.”

The design goal has been to produce a motorcycle with a four-stroke engine whose power characteristics closely resemble those of the existing and very successful two-strokes-except there will be more top-end power and a better spread of torque. Because Yamaha has a great asset in the proven handling of its YZR500 chassis, the engine configuration chosen-a conventional transverse inline-Four-is one that fits this chassis with the least incompatibility.

It is wise to base a new project on proven hardware, then add novelty only as circumstance requires. The goal is to win championships, not destroy tires with brilliant but otherwise pointless technology.

Shiohara, who has worked on this project since 1999, says the YZR-M1 engine has “no relation to the YZF-R1 streetbike motor” and that it is “well under the 990cc limit.” Output is presently “greater than 200 horsepower at 15,000 rpm.” This reminds veteran observers of Yamaha’s bhp claim for its 1978 TZ500 racer: “More than 100 bhp at 10,000 rpm.” This is amusing because the TZ produced much more than 100 bhp, but at 12,000, not 10,000 rpm!

Features of the Ml engine include the use of five valves per cylinder, a quickchange cassette gearbox, dry clutch and electronic engine control. Pneumatic valves were considered and rejected “because there is already enough power.” Four-piston Brembo brake calipers-the choice of many teams in both GP and World Superbike-are used at the front on “radial-style” mounts.

Photographed at the bike’s most recent test in Mugello, Italy, Shiohara appeared watchful and a little appre-> hensive. His reputation is strong; his past work includes the original 1972 OW-20 (the 500cc predecessor to the famed TZ750), the unusual OW-61 of 1982, early 250 and 500cc YZRs, and the YZM400F works four-stroke motocrosser. Thirty years of distinguished work is excellent preparation for an effective, conservative new GP engine. After the Mugello test, developmentrider John Kocinski said, “We are very close to 500cc performance, but we’ve got a little way to go.”

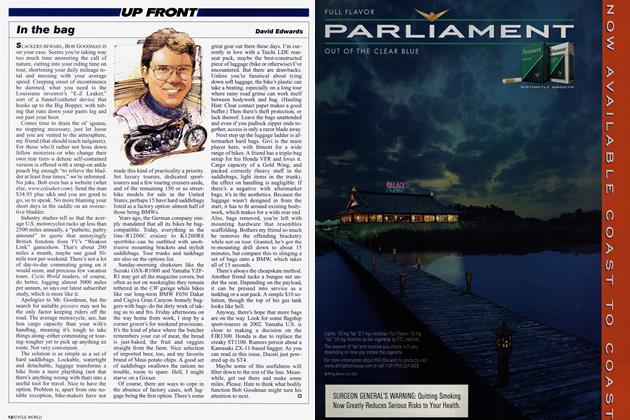

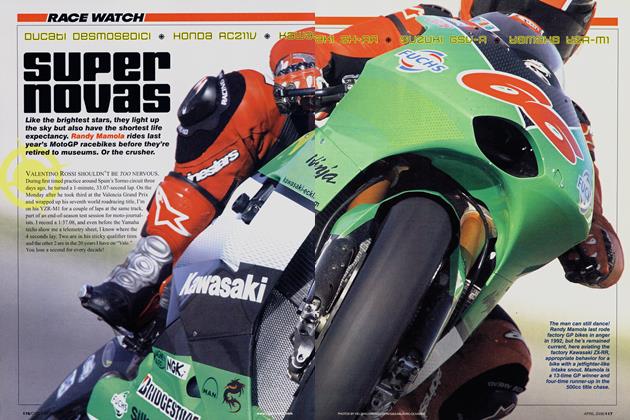

Honda’s V-Five RC211V is likewise on the test circuit. Its displacement is rumored to be only 810cc. If this seems surprising, remember the last RC45 Superbike accelerated and “top-ended” equally with the then-current NSR500. As Yamaha’s Shiohara said, the job is not to make record power, but rather to duplicate the handling and performance of existing 500s-plus a bit more.

Those who’ve seen the Honda say it is very small. In photos, however, it looks long. This may be a result of the smaller 16.5-inch wheels or the abbreviated tailsection. It may also be that to use the higher acceleration potential of the large four-stroke, the chassis has been extended slightly. Acceleration is limited by front wheel lift, and the existing 500s will throttle-wheelie at more than 125 mph. The only way a four-stroke can gain a performance edge in this range is from finer control of early acceleration-always a fourstroke advantage-and by raising the wheelie threshold via a longer wheelbase or more radically forward engine placement. Every option has its costs!

A four-stroke’s extra height, result-> ing from its overhead valves and cams, makes it desirable to lower the gas tank to preserve a low polar moment. A tall engine (like the SauberPetronas Triple shown recently) more strongly resists the rider’s efforts to flick the machine into and out of turns. What appears to be the Honda’s gas tank is entirely intake airbox, while the fuel is mainly under the seat. To make room for this tank, the shock is moved down through the swingarm, with the top of the damper attached to the arm itself-not the chassis-and compressed by linkage from beneath, a system similar to Suzuki’s FullFloater design. The aluminum-beam chassis is conventional except that the forward end of each beam splits in two, providing side entries for the two air intakes. This is a big improvement over the common practice of weakening the beams by simply cutting holes through them.

The three exhaust pipes from the front cylinders join into one collector, and the two pipes from the rear bank into another. The two collectors join into a single exit pipe on the right side of the machine. Sorry, traditionalists, no blaring individual megaphones. Those who have heard the Honda run say it sounds like a higher-revving RC45.

Looking at the right side of the bike, fairing off, you see a deep, bolt-on oil sump like those on Suzuki Superbikes. This prevents oil from sloshing away from the pump pickup during violent maneuvering. The sump is on the right side of the engine, leaving room for the front exhaust collector to pass to its left.

Front suspension is Showa, with fourpiston Nissin billet brake calipers in the modern fully rearward position. A large radiator array is conventionally mounted, with the water pump on the left side of the engine under the hydraulic clutch-release cylinder. The dry clutch barely projects beyond the frame beam on the right, testifying to the relative narrowness of the engine.

Honda GP bikes are maximum eye candy, with every feature executed in fine detail that no showbike can equal. In comparison, Yamahas resemble rugged, workmanlike combat equipment. It’s a matter of style.

The real problem in making fourstrokes of any displacement perform with current 500cc two-strokes is mass properties-how much weight there is and how it is distributed. Rules specify a weight for each engine configuration. The lowest minimum is for Twins, while more is required for Triples, Fours, oval pistons, etc. Yet because it’s easier to maneuver while carrying a 24-pound cannon ball than a 24-pound, 12-footlong ladder, how that weight is distributed on the machine will be equally important. This determines how easy it is for its rider to roll it over, to set it turning and to recover it from any loss of control. Because so much refinement of this kind has already been applied to current 500s, improving handling despite the extra mass of four-stroke valvegear will not be trivial.

Formula One cars are radically different from road-going automobiles, but the new four-stroke GP bikes are so far almost indistinguishable from ordinary sportbikes. Only a committed gearhead would notice one parked in a row of other sportbikes. It’s unfortunate, but they lack F-l’s “radical chic,” which is based upon obvious things like ground effects, carbon chassis and exotic, 18,000-rpm V-10 engines. The reason is that today’s wonderful production sportbikes have already adopted every racing innovation except slick tires and carbon brakes. What will actually be different? As you can see from the photos of the Honda and Yamaha, these bikes carry a lot less muffler volume than we are used to on streetbikes-less even than is normal on Superbikes. Honda’s canister is short, while Yamaha’s is long and small in diameter. This results from the new higher noise level permitted. The new GP bikes won’t even be much lighter than the lightest sportbikes-both of these bikes are built to the prescribed 320-pound minimum.

Plenty of people are wildly enthusiastic about four-stroke GP racing. The idea seems to be that although big sponsors have tended to leave 500cc GP racing (Rothmans, where are you?), the magic words “four-stroke” will bring them back in environmentally conscious droves. Let’s hope it’s true. Such sponsors are essential to support this change.

And what might skeptics say? Spoilsports and sourpusses point out that these new machines are actually “lowtech Superbikes,” and suggest that Yamaha’s YZR-M1 is “just an R1 on Weight-Watchers.” Not only are the bikes quite conventional, but the FIM has given them such generous displacement and weight limits that they need nothing fancier than production-level technology to hit their horsepower goals. Even a pushrod motor might be able to make the grid! This is exactly what HRC’s Yasu Ikenoya claimed months ago when he said that the new GP bikes would employ “normal” technology. It may be that instead of improving the breed, these bikes are intended simply to breed. That is, to be spun off as new production bikes in a year or two. This, in fact, may explain why the Honda has five cylinders-it provides unique sales appeal.

On two wheels, almost all GP entries are either by factories or of machines made by the factories. In F-l, specialist firms such as Cosworth and Ilmor build most of the chassis and engines. Mercedes, whose racing cars were once the epitome of advanced engineering, now commissions its racing engines from Ilmor. Only BMW, Ferrari and Honda still design and build their own.

What does this tell us? It tells us that F-l cars and their engines have become so utterly different from production that little of technical use to the car business can be gained from racing. Therefore, racing has evolved into a separate, freestanding industry that exists to sell its services as advertising. The huge success of F-l as an advertising medium affords the top team an annual budget on the order of $300 million. This money comes not from sales of automobiles, but from the giant ad budgets of cigarette and computer makers. For them, these sums are routine.

On two wheels, there are few independent producers of competitive bikes and engines. Teams depend on outside sponsors, but the engineering still comes from the factories. This is so because racing and production motorcycles are still so closely related. Change is, however, clearly taking place. Ducati, whose record year-2000 profits came to about $9.45 million, is said to be contemplating spending $30 million for GP development and startup, followed by annual operating costs of $10 million. Obviously, this money has to come from outside. The big question is, why will four-strokes attract bigger sponsors than the existing two-strokes?

Racebike engineering has already separated financially to some degree from production engineering, so it is no longer just an expensive parasite. This is because factories presently lease racebikes to teams for an approximate annual cost of $ 1 million per seat. This money then helps pay the factory’s racing R&D cost.

With four-strokes, the reverse relationship becomes possible. Given that race and production bikes look so similar and employ the same technologies, it makes good business sense to let external racing sponsors pay for the development of racebikes that are really just next year’s production streetbikes, temporarily without lights and disguised in titanium and carbon-fiber. Instead of sponsors just offsetting race R&D through lease costs, in the future they may also pay for product development. Racing will not only sell the sponsor’s product on worldwide television, it will also fill the public with an inexpressible yearning for the upcoming production versions of the racebikes themselves. Go get those sponsors, and good luck!

If it works, productionized YZR-MIs and RC211 Vs could be rolling into your local showroom soon. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue