IMMINENT CHANGE

RACE WATCH

Is NASCAR's Moto-ST series a template for America's roadracing future?

KEVIN CAMERON

THERE ARE DAYS WHEN I THINK I'D BE HAPPY TO have AMA-managed roadracing just continue as it always has—like an underpowered airplane, moving but not quite able to rise off the runway, seemingly capable of greater things, yet never actually attaining greatness.

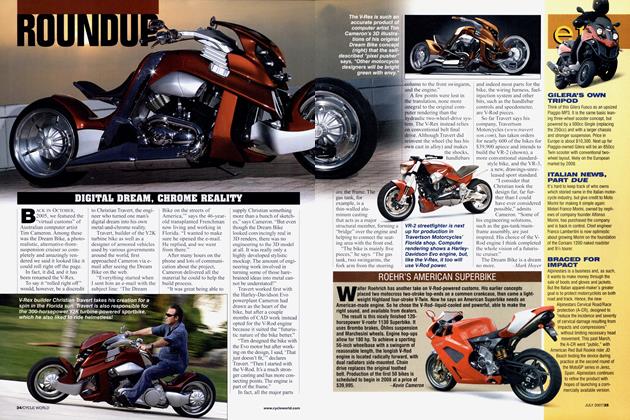

Instead, we are jolted by rumblings of imminent change. Biggest is the hoarse whispering that International Speed way Corporation (i.e. NASCAR), seeing the current disar ray of the AMA, may expand its admired Moto-ST Twins endurance roadracing to some kind of full national pro gram, supplanting the AMA

Turn your ear in a different direction and you might hear that ISC is sniffing at dirt-track and even at some kind of revival of the old, multi-disciplinary Grand National series. Tune to a different frequency and the signal switches to, "Why not a stand-alone Daytona Supercross? Good clean business, in and out in a day, big gate, big money. And who says it has to share the program with the Daytona 200?'.'

Then there's the evidence of our eyes. In the past, when the Daytona 200 ended, no sensible person tried to leave the in field before 7 p.m.-the gridlocked mass

of spectator vehicles stopped all move ment. I have purposely never looked up at the stands during Speed Week-too depressing-save during the glory years

when 747s full of European and Down Under fans flew in to land at Daytona Regional Airport (as it then was). This past spring? I headed for my rental the

moment the pressroom rider interviews ended, and I was at the exit tunnel in 5 minutes. I have no way to count admissions but by this rough measure, this was the lightest Daytona ever.

Why? People are confused. How many still come to the races, thinking they are on Sunday? No, now they’re on Saturday. How many know that although Superbike is the featured AMA class, the 200 is now a 600cc event? What is Superstock 1000? (Answer: Nothing-it will be done away with after 2008). Who is national champion? Of what class?

In 1993, after years of effort by nowdeparted ex-president Ed Youngblood and others, professional racing was separated from the AMA itself. This was done to escape the provincial interference of the old-time Board of Trustees, to create an agile organization that could make decisions quickly and to help solve certain tax issues of a non-profit corporation (the AMA). The resulting Pro Racing organization, Paradama, was staffed with experienced people to steer racing to commercial success.

Yet something over a year ago, the head of Pro Racing, Scott Hollingsworth, was abruptly fired Paradama disbanded and Pro Racing taken back into the AMA to again be just another department alongside membership and amateur racing. When at the time I asked various insiders why, I could not get a clear or compelling answer.

That dust had scarcely settled when the infamous Daytona pace-car incident took place. When a “pace-car situation” arose in the 2006 200, the pace car pulled onto the track without its observer, mistakenly taking up a position that (some feel) altered the race results. The usual suspects were rounded up and heads rolled but again, the AMA had revealed itself as not quite ready for prime time.

to this, ISC had reportedly found in Hollingsworth a man they thought they could do business with-someone who understood that racing is a fast paced entertainment business. Why was he fired?

First, a word about ISC: This is a very tsuccessful organization that does not r suffer fools gladly. They don't like relin quishing control over their racetrack to others, and they don't particularly like dealing with other sanctioning bodies. Although they are not the only game in town, their influence with many other race tracks is respected.

No one who wants to run races in the U.S. can give offense to ISC. In the past, there have been proposals to run the 200 at some other track or to begin the AMA season with some other event. For the most part, those ideas have been batted down, the only exception being the Phoenix opener in 1993, ’97 and ’99.

I was once present with AMA people in the ISC offices-the famed “smokefilled room” of NASCAR legend. On the day previous, Roger Edmondson (today an ISC employee, but in those days an AMA contractor) had discussed the feasibility of operating U.S. roadracing under ISC rather than AMA organization. Then Bill France Jr. came into the conference room and said, “That last show you ran here was a stinker. We won’t run another show like that. We don’t want to be in the sanctioning-body business, but we’ve done that when we had to. We’ll give you people another chance here. If things go right, everything’s okay.”

This shows that ISC is a de facto partner of AMA, like it or not, and not “just a track owner” they do business with.

Three years ago, ISC told Hollingsworth, “The next 200 will not be a lOOOcc event. There will be a 200, but whose bikes they are is unimportant.”

That’s not negotiation. The result was the present structure of a short Daytona Superbike race, followed by a 600cc 200. ISC does not want to run anything on their oval at over 180 mph.

A lot has changed in past decades. At one time, the AMA was looked upon as the essential interpreter between the business world of promoters and track owners, and what was then seen as the rowdy outlaw world of riders and fans. Today, riders and team owners are themselves businessmen, suggesting the question, “Just what does AMA uniquely do for racing?” If the answer is “nothing,” racing could be managed by other interested organizations.

The success of Supercross suggests otherwise. The promoter handles off-track matters while the AMA takes care of ontrack in a successful division of labor. What promoter wants to handle rider licensing, insurance and the multitude of

tasks that go into establishing a national championship?

Yet U.S. roadracing still seems like an undervalued stock whose value could rise with suitable management-as happened in GP racing. I like the analogy of the $20 bill lying on the sidewalk. If no one claims it and no one’s nearby, it’s yours.

The weaker, less skillful and less organized the AMA appears to outsiders, the more U.S. roadracing resembles that orphan $20. It is for this reason that many experienced insiders are saying, “Something’s going to change soon. I can feel it happening.”

At this point, let’s return to how Hoi-

lingsworth came to be fired and Pro Rac ing taken back into the AMA-events viewed by many as reactionary. Marriages typically fail because the partners have differing world views, not because either partner is particularly blameworthy. Dif fering world views complicate every mutual decision and embitter every

disagreement. So it was between Pro Racing and its AMA parent. AMA lives by old-time Midwestern ideas of fiscal re-

sponsibility and a Kiwanis morality. Pro Racing was created to play in the risky world of TV rights and entertainment

politics, but to AMA it was “underperforming.” To the AMA, 3 percent bank interest is a risk to be pondered, so Pro Racing’s normal functioning worried the home office. Pro Racing could have retorted that in a nation of 10,000,000 motorcyclists, AMA membership of

200,000 is underperforming as well-a bare 2 percent. Pro Racing thus spent much of its time parrying AMA’s concerns and attempts to reestablish control. This, as in marriages, provoked ever-sharper conflict. The details of the final explosion are unimportant, but it returned AMA roadracing to its former status as just another division, and Hollingsworth was out.

As before and for so many years, new ideas must again bang their way to approval through the AMA’s pinball-like maze of committees and boards of reversal. Direct questions are parried with vague answers. Who’s responsible for this decision? Senior staff. But who? That “came from above.” No one is saying, no one can be quoted. There are moats and castle walls, a special way of thinking.

One hope is that clear rules, applicable to all, may dispel the fog of the past. Worst of all has been the so-called “briefcase rule.” This, like the “enabling laws” of dictators, made published rules irrelevant by granting officials power to make any ruling they deemed necessary “for the good of the sport.” Dirt-track in its long decline has attracted at least five revival plans, but all had to leave the Harley-Davidson XR establishment in place-and unchallenged. Homologation for dirt-track has not been a clear rules process but has required administrative approval outside the rulebook-the “briefcase rule.” This has sent a message to potential new competitors, “You can run, but you mustn’t win.” And it mandates that management “fix what’s wrong with dirt-track. But don’t change anything.”

There’s no lack of proposals. ISC in the 1950s arm-wrestled Detroit for control of racing, for it’s understood that while manufacturers must stand out in order to sell vehicles, ISC must sell drama, not one-make dominance. This has led to the “NASCAR model,” which fields nearly identical vehicles racing on ovals under managed conditions that favor close contests and dramatic finishes. Singlebrand domination, of the kind that manufacturers need, is absolutely forbidden. Skeptics regard such contest management as “four-wheel Pro Wrestling,” but its many admirers point to NASCAR’s dominant position in U.S. auto racing and its decades of success.

Could the NASCAR model work on two wheels and on a variety of non-oval road courses? Right now, AMA roadracing does field near-identical vehicles (every bike is inline-Four-powered, save for the odd Buell or Ducati), but this uniformity comes from the market and the manufacturers, not from the sanctioning body.

ISC's Moto-ST endurance roadrace experi ment provides variety in sound and ap pearance by excluding all but Twins lim ited to three horsepower levels-i 18,90 and 75 hp. Critics dismiss this as "a slow race of boutique brands," but it can also be seen as research, exploring novel class

structures while developing the infra structure to run a motorcycle racing series. There are other ideas. There are now no fewer than 12 brands making 450cc off-road four-stroke Singles. Some peo ple are now thinking back to when an AMA Grand National champion had to

earn points in mile and half-mile flattrack, TT and roadrace. Why not a new Grand National series, based on these available bikes and adding to it the novelty of Supermoto?

There have been several AMA schemes to save “our dirt-track heritage.” Great pavement champions have come from this source, but the long decline of dirttrack has left us with maybe 20 events per year whose total spectator draw is comparable to one or two Supercross stadium events. Is this a heritage, as many believe? Is it just a “living museum,” as others claim, as relevant to today as scythes and flails?

Should AMA continue this fight at all? AMA clearly benefits American riders in government advocacy and member services. Does the racing business-whether roadracing, flat-track or MX/SX-fit into this AAA-like structure? It must, for when insiders tried to buy Pro Racing from the AMA prior to Paradama’s dissolution, the parent organization refused to sell or even to discuss the matter.

U.S. motorcycle racers are dependent on turnkey bikes. Gone are the days of building your own Triumph or Harley with a Branch or Axtell head, stuffing it

1thto a Red Line or other trick frame and completed with a long list of accesso ries. In the early 1980s, anyone could be come "one-day competitive" by going to the dealer, buying an MX bike and rid ing gear, then hot-footing it to the track

that same afternoon. No assembly required, no costly trips to airflow gurus or machin ists-just put in gas and oil. In 1986, Su zuki did nearly the same thing for roadra cc with the first of its GSX-Rs. Cheap, raceable 600s soon broadened the concept.

Today, the grass-roots culture of motor cycle innovation has all but disappearedit now comes in the crate and at a price cheaper than anything we could build. Roger Edmondson has for 15 years considered the idea of a spec racer-may-

be a 500cc Single in a one-design chassis-as a basis for an entry-level class that would emphasize rider ability, not yearly obsolescence. The industry told him the costs would be too high. Some wonder if the new 450cc MXers could be that turnkey bike.

A problem here is that these 450s are developed to survive the 3 seconds of full throttle it takes to accelerate to a Supercross Triple-not many times wide open from the Daytona chicane to Turn 1. Why not just slip those four-stroke hot numbers into the race-ready aluminum Yamaha TZ250 chassis that are now leaning, obsolete, in so many garages? (AMA terminated the 250GP class three years ago.) Brakes, handling, light weight-what could be better? Sorry folks, that tooth-loosening single-cylinder vibration at 13,500 revs would require mid-race frame-welding stops. And what about the primary ratios, designed for a 50-mph top speed? Where do we get race-qualified, six-speed close-ratio gears? No big deal? Or is it a deal-killer, given that backyard ingenuity has given way to turnkey as U.S. racing’s central concept?

It’s no cinch to make racers out of bikes designed for other duties. We could prooftest all our new gears, cranks, aluminum chassis, primary ratios and pistons for the higher duty cycle-let’s say 4000 hours at $2500 per hour for equipment, overheads and personnel. That’s $10 million, and I can’t write the check. Know anyone who can? Why yes-the manufacturers, who are already producing today’s sportbikes. They qualify the durability of every sportbike in just that way, and the large market pays the bills in the traditional way.

Maybe ISC can create a new form of

motorcycle roadracing and make it successful under their NASCAR model. Maybe some kind of kit class could somehow succeed-with appropriate support from industry or other large sponsors. But it is my feeling that the most likely kind of roadracing to survive here will be based mainly upon the raceable turnkey sportbikes we already have.

It is less likely but not impossible that it will be based upon attractive and affordable spec bikes, or upon any bikes constructed to suit a formula put forth by a sanctioning body. The drawback, according to some, is that any sportbike-based formula gives the top manufacturers >

major leverage over motorcycle sport. Attempts to escape this include racing based on classes of spec bikes or on prod ucts of more easily managed manufactur ers (the so-called "boutique brands," eager for any exposure), or upon equipment

originally built for another purpose-such as the new 450cc off-road bikes. Future U.S. roadracing will have to be affordable-our racers are not country-club swells or business kingpins who comfort ably write big checks. Neither will there be

a mass return to machines homebuilt from extensively modified parts. Let us now order pizza, open our drinks and sit back to watch the tectonic plates of our sport as they collide and rearrange themselves.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue