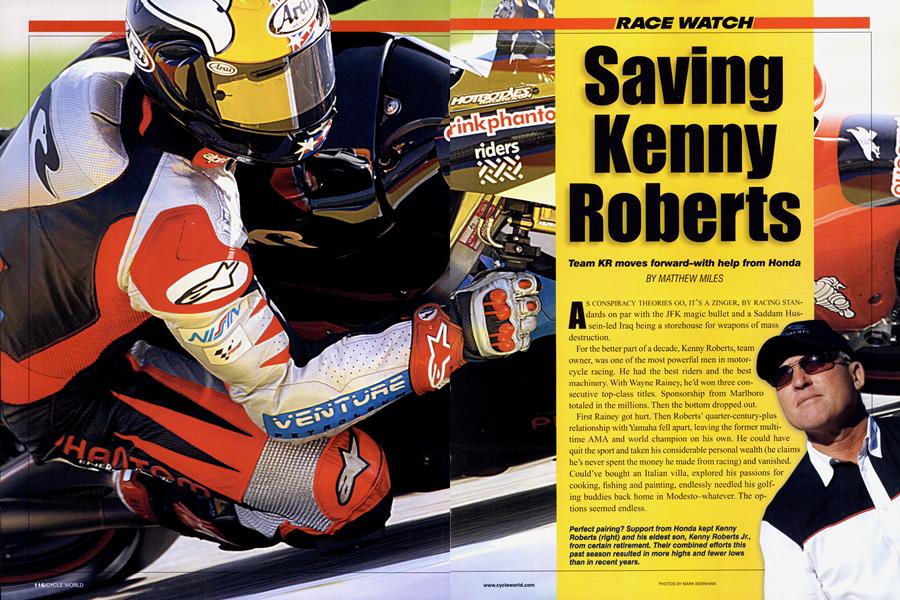

Saving Kenny Roberts

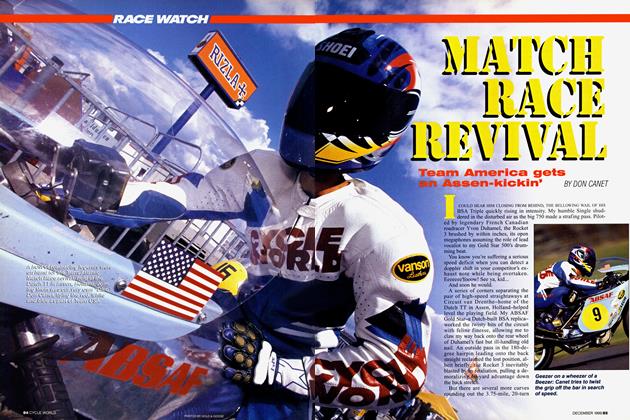

RACE WATCH

Team KR moves forward-with help from Honda

MATTHEW MILES

AS CONSPIRACY THEORIES GO, IT’S A ZINGER, BY RACING STANdards on par with the JFK magic bullet and a Saddam Hussein-led Iraq being a storehouse for weapons of mass destruction.

For the better part of a decade, Kenny Roberts, team owner, was one of the most powerful men in motorcycle racing. He had the best riders and the best machinery. With Wayne Rainey, he’d won three consecutive top-class titles. Sponsorship from Marlboro totaled in the millions. Then the bottom dropped out. First Rainey got hurt. Then Roberts’ quarter-century-plus relationship with Yamaha fell apart, leaving the former multitime AMA and world champion on his own. He could have quit the sport and taken his considerable personal wealth (he claims he’s never spent the money he made from racing) and vanished Could’ve bought an Italian villa, explored his passions for cooking, fishing and painting, endlessly needled his golfing buddies back home in Modesto-whatever. The options seemed endless.

To hear Roberts tell it, Honda was behind the blow-up with Yamaha. All those cylinders and pipes made by Bud Aksland back home in California and at GP Motorsports, Roberts’ base in England? The 1991 -style ROC chassis that Rainey raced during the latter half of ’93? Pie in the face, Honda execs allegedly told their counterparts at Yamaha. Get rid of that guy; he’s bad for business.

So Roberts struck out on his own, emptying sponsor coffers to produce his own motorcycles-first two-strokes, then four-strokes. Try as he might, hiring the best Formula One experience he could dig up, Roberts was in a downward spiral that only began to right itself this past season with aid fromyes, conspiracy theoristsHonda.

Maybe Honda is different today than it was then. Maybe it’s all part of a covert master plan in which Roberts is just a pawn. Maybe someone in Japan felt sorry

for Roberts. Whatever the explanation, one thing is certain: The engineers who were in the trenches when Roberts was winning titles as a rider and later as a team owner, heavy hitters with names like Kanazawa, Horiike and Yoshii, are now pulling the strings at HRC.

Carmelo Ezpeleta, CEO of Dorna Sports, rights-holder to MotoGP, freely admits that he was “involved” in brokering the deal between Honda and Roberts. In fact, he was the bridge between the two parties. “We try to do as much as we can to help the teams-especially Kenny,” said

Ezpeleta. “He is a big name, a big property, for MotoGP. We will do whatever necessary to keep him here.”

Through a translator, Honda approached ^Roberts at the USGP in 2005. “We thought, ‘That’s odd,”’ he said. “Why would they come and tell us that if we

had engine-supplier problems in 2007 they could supply us?”

Honda knew what Roberts didn’t-that his engine supplier at the time, Austrian bike-maker KTM, was pulling the plug on its MotoGP program. According to Roberts, KTM CEO Stefan Pierer said all along

that if MotoGP went to 800cc, they couldn’t do it with the existing motor. “I told him,” Roberts said, ‘“If you’re worried about rule changes, you need to get out now, because you can’t predict what the rest of the people are going to do.’” By “the rest of the people,” he was referring to Ducati, Honda, Yamaha and the other members of the Motorcycle Sports Manufacturer Association.

Pierer took Roberts’ advice: He got out-with seven of the 17 races still to run. Not only did Roberts have to finish out the year with his mothballed V-Five, he had to find an engine supplier for 2006.

With no other help in sight, Roberts looked to Honda for engines for 2007 and ’06. Honda agreed, even if it wasn’t part of their original plan. “That’s why we had one rider,” Roberts said. “They couldn’t supply engines for two riders.” That rider, of course, was Roberts’ el-

dest son, Kenny Jr., the 2000 world champion, who had ridden two-stroke Yamahas and the Modenas KR3 for his father before joining Suzuki in 1999. Let go by the Japanese factory after the ’05 season, Roberts Jr. was for all intents and purposes retired. “I was done,” was his emotionless summation.

Roberts Jr. had tired of making all the sacrifices only to finish mid-pack on the underdeveloped GSV-R. “I told Suzuki that when they figured out I wasn’t able to ride quick any more,” he said, “I would stop.” Money wasn’t an issue. Suzuki paid well, and Roberts Jr. isn’t drawn to big houses or exotic cars. He joined Team KR for one reason: His dad asked him.

“I don’t even know if he has a contract,” shrugged his father, an indication of the informal nature of the arrangement.

Warren Willing, another longtime Roberts associate, also returned to the team as race engineer. After guiding Roberts Jr. to the title at Suzuki, Willing spent several seasons working with KTM on its twostroke GP program. Like Kenny Jr., Honda engines, Öhlins suspension and Michelin tires, Willing, according to Roberts, was “another piece of the puzzle.”

Using a non-running RC21IV engine as a placeholder, GP Motorsports designed and built from scratch a complete motor-

cycle-480 individual pieces-in a little more than two months. Completely upsidedown only weeks earlier, Team KR was once again going racing-with new resolve.

Pre-season testing appeared to go well,

with Roberts Jr. posting competitive lap times against proven machinery. A rider of his caliber brings more to a team than on-track speed. Drawing from his experience as a private pilot, he called for better organization-redundant programs that wouldn’t allow silly mistakes.

“When I got here,” he said, “there was disarray in that area. There were no checklists, no color coding, no way to know if you were right or wrong in any area.”

Roberts Sr. admits that his guys had

gotten sloppy. Now, everything goes off like clockwork. “A lot happens when you fall off the competitive edge, when you don’t have that adrenaline anymore to beat fast time,” he said. “When you don’t have that kind of pressure in your job, you’re not going to do as good as you can.”

Within a few weeks, Roberts Jr. had evaluated three chassis, taking advantage of GP Motorsports’ ability to quickly rethink concepts and, if necessary, abruptly change directions. Further accelerating the process was the absence of language barriers-everyone spoke English. Team Manager Chuck Aksland said Honda was impressed by what they saw. But, as Roberts noted, Honda had also been impressed with his Proton VFive, at least initially.

At the season opener in Spain, Roberts Jr. finished eighth but slipped to 10th in Qatar and 13th in both Turkey and China. After four races, he was 12th in points. “Our expectations, obviously, were quite a bit higher,” admitted Aksland. There was even talk of putting another rider on the bike, if only for additional feedback. “Do what you have to do,” was Roberts Jr.’s alleged response. At this point, only the Honda engine-always perfect from start to finish-was beyond criticism.

Out of a meeting held with HRC engineers in China came suggestions for fur->

ther chassis revisions, namely in the steering-head area. “Really, what that conversation did was to prioritize things,” explained Aksland. “We had some ideas for direction; one that was sort of fourth or fifth on the list got put up to first. Some of those ideas just got shelved. It saved us a lot of time.”

Early framework was similar to the John Barnard-designed CNC’ed-fromsolid chassis that were home to the Roberts V-Five and KTM V-Four-but with longer front engine mounts that flexed to enhance grip at extreme lean angles. Eater came longer main beams, which were fabricated rather than machined because they were simply too long to be made on Roberts’ specialized equipment.

Modifications to the rear of the bike were made in tandem. With the complex Barnard swingarm, shock swaps took up to 12 minutes-too long with MotoGP’s newly instituted non-stop race format. A more mechanic-friendly design cut changeover time to a couple of minutes but at an initial cost to rider feel.

Fifty percent of what Honda recommended-visible reworking and strengthening of the steering head-was completed in time for the French GP (mechanical DNF), another 25 percent by Italy (another eighth) and 100 percent for a test on the Monday following the Italian

round. Now, the bike would turn, Roberts Jr. said. “I wasn’t fighting to lay it down and keep it in the comer.”

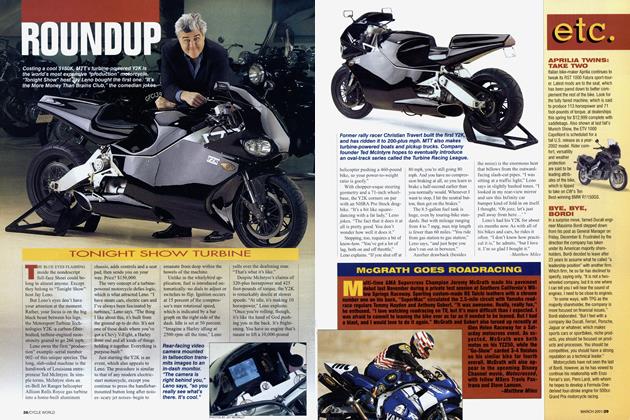

Back in Spain, round seven at Catalunya, Roberts Jr. both qualified and finished third-the team’s first podium in a decade. He backed it up with a fifth in Holland, half a second aft of class rookies Dani Pedrosa and Casey Stoner, and another fifth in Great Britain. Finally, the team had a base setting. How much sooner might the bike have come around if it employed a test team, a luxury not available since the Yamaha days?

Another front-row start in Germany (narrowly missing pole) put Roberts Jr. smack in the thick of things at the start, racing not only experienced riders he knew and trusted but young hardliners fresh from the bellicose 250cc GP ranks. Ten laps in, while running with the leaders, he T-boned the Honda of Makoto Tamada, putting both riders in the gravel trap.

It was an uncharacteristic mistake by a rider who takes the long view, who epitomizes discipline, who risks only what is absolutely necessary to realize his goal. In recent seasons, the odd wet race excepted, Roberts Jr. hadn’t spent much time at the pointy end of the pack, and he made it clear that he didn’t want to be “that guy,” the rider whose unwarranted mistake altered the outcome of the championship, particularly when a fellow American had the points lead. Morality of it all aside, the fact is he was now able to ride at 100 percent of his ability. Good performances were expected.

Back on U.S. soil, Roberts Jr. led every practice and qualified third at Laguna Seca, a night-and-day improvement

from the previous year’s performance. “He’s riding at the same limit he rode to last year on the Suzuki,” explained his father, “but he’s just riding a better horse.”

In the race, run in blistering heat on a deteriorating surface, Roberts Jr. got the holeshot, faded, then mounted a comeback in the latter stages to come home fourth. His performance at Laguna, similar to those at Catalunya and the Sachsenring in Germany, was hampered by a lack of grip, particularly driving out of slower comers, compensated for by tweaking the traction control to its max. Still, he was forced to ride “harder than I would like to.”

Ahead of him were three Hondas-the works bikes of Hayden and Pedrosa, and a customer RC211V ridden by Team Gresini’s Marco Melandri. This highlights Team Roberts’ unique position: It is neither a factory team nor, like Gresini, Konica Minolta and LCR, a satellite effort. Time was, use of a factory bike for a season set you back $l million. Does Roberts pay for his engines? Yes.

“Satellite teams get information off what settings are available,” said the younger Roberts. “Their stuff is at the end of the road, but we’re always trying different things.” It is in that respect he would like to see a closer relationship with Honda, a collaboration in which the two share information. “Whether it’s more>

electronics or factory engines, whatever on their part is a good-faith gesture that allows us to help them,” he said.

Even going it alone, as it were, the team continued to make progress. There were highs (fourth in the Czech Republic) and lows ( 14th in dry/wet Australia) and, just as in the post-Mugello test, real progress following the Japanese GP. “It’s the best the bike has ever been,” confirmed Roberts Jr.

Getting to that point took most of the year, no fewer than six chassis and a lot of hard work, with the sum total giving Roberts Jr. the opportunity to finally race for an all-important win in Portugal. Coming from 13th on the grid, he passed Toni Elias and Valentino Rossi (“my old rival”) for the lead and led across the line, but it was one lap too soon. “Riding like a devil,” as Rossi called it, Elias earned the win, with the Italian second.

Had the season ended there, Team KR could have gone home happy. Its rider had scored points in all but two races and was sixth overall in the standings, with only a Yamaha (Rossi), three Hondas (Hayden, Melandri and Pedrosa) and a Ducati (Loris Capirossi) in front of him.

While the world watched as Hayden and Rossi slugged it out in Spain, Roberts Jr. struggled to eighth. Nowhere was the frustration more apparent than with slumpshouldered Willing. “You just want to move forward,” he said dejectedly.

If Ezpeleta has his way, Team KR will move forward-with or without two riders or a long-term, multi-million-dollar>

sponsor. “The problem is that Kenny is an American,” he said. “The impact in America is not enough, right now, for MotoGP. I hope that American companies will understand how important it is

to be in the biggest two-wheel series in the world. In the meantime, we will try to work something out.”

A little more help from Honda would not hurt. □