DAYTONA SUPERBIKE 200

WINNER: JOHN ASHMEAD

Now that's racing.

PROBABLY THE MOST OVERused and inadequate two words in the world of motorsports are “that's racing.” By definition, there can only be one unqualified success story in any given race, while there are a multitude of failures, stories where the only recourse is to load up the van quietly and look forward to the next race. If someone asks questions, a racer can find some slight gratification in those two words only because there's really nothing else to say.

But if any two words can sum up the 1989 Daytona 200. those are the ones. The 2Ö0 generated that phrase over and over this year. First of all, take the combined cases of David Sadowski, Rich Arnaiz and Gary Goodfellow. All three of them led the 200 at one point or another. None of them finished. For Goodfellow, the charging. 34-year-old New Zealand native w ho led the field on the first lap and was still in contention for several laps after that, the end came in the form of oil on the track. He crashed on the sixth lap and ended up in the hospital with a broken arm. foot and ribs. “That's racing,” you say? There's more. Sadowski. rider for the revitalized Vance & Hines roadrace effort, was in second place after leading briefly and then dropped out with transmission trouble. And ex-dirt-tracker Arnaiz, on an unlikely Yamaha FZR750. was actually in front of the field w hen he crashed out of contention. That's racing, and that's racing again.

Then there was Ruben McMurter. the Canadian champion who always does well at Daytona. Running near the front of the pack on Bubba Shobert’s old VFR750, McMurter was a victim of what he called “pacecaritus.” This was the first year Daytona used a pace car to regroup the field during yellow-flag periods. NASCAR-style. While workers cleaned up the oil that took out Goodfellow, the pace car slowed the pack and McMurter’s bike then developed a vapor lock. “Racebikes aren't meant to punt around behind pace cars.” he said. His race was over.

But the most demoralizing hardluck story of all belonged to the entire Yoshimura team. They rolled into Davtona with all the confidence of a Pro wrestler with a script that says it's his turn to win. And why not be confident? The team had overwhelming favorite Doug Polen on the fastest machine on the track. And just in case something happened to him, there was Scott Russell as a backup and Jamie James as his backup. Surely lightning couldn't stike all three riders. Or could it?

Scott Russell was the first lightning hit. The 200 had a false start when Russell bogged off the line and was rear-ended by another rider. After the restart, Russell pushed hard but suffered chain-derailment problems and lost several laps to the leaders. Lightning-strike number two hit Polen himself. It was almost the h a 1 f'way mark and Polen was solidl~ in front. He had pitted once, losing the lead for just a few laps. and then was back on top when Sadowski pitted. But Polen's trouble started on lap 24 in the form of an oil leak that would eventually take him out of the race.

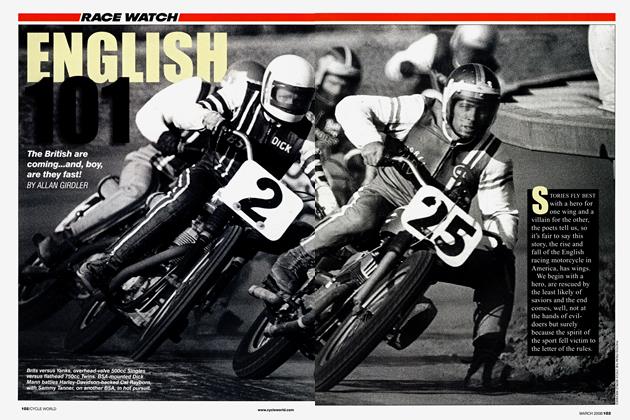

RACE WATCH

That left Jamie James as Yoshimura’s sole hope, and it looked like he would be enough. He had an insurmountable lead two laps from the end of the race. But it wasn't to be. He thought he was running out of gas just before the white flag came out, so he pitted. It didn't help—the problem turned out to be ignition failure. He got back on the track and sputtered in to a second-place finish, ending Yoshimura's hope for a second consecutive Daytona victory. It was another case of That’s Racing. Times three.

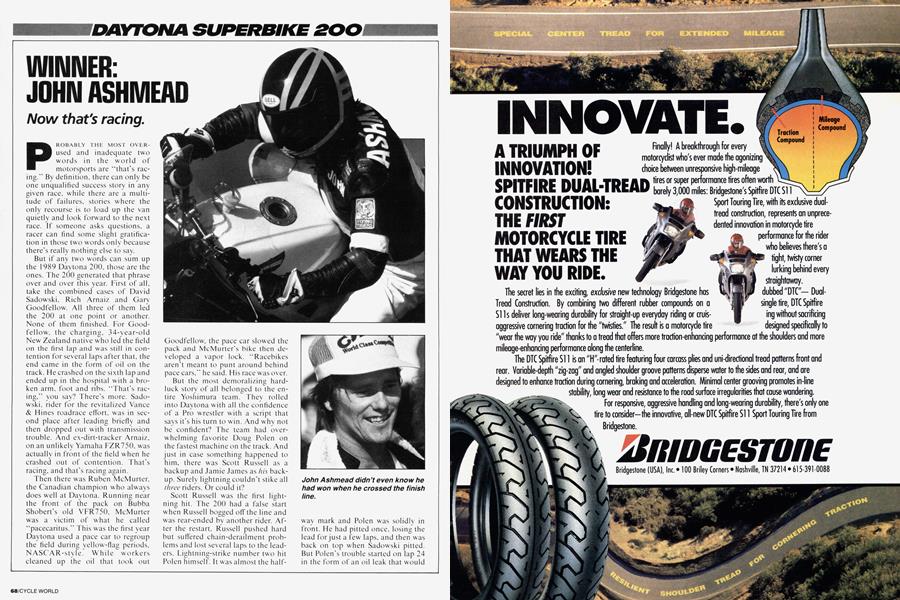

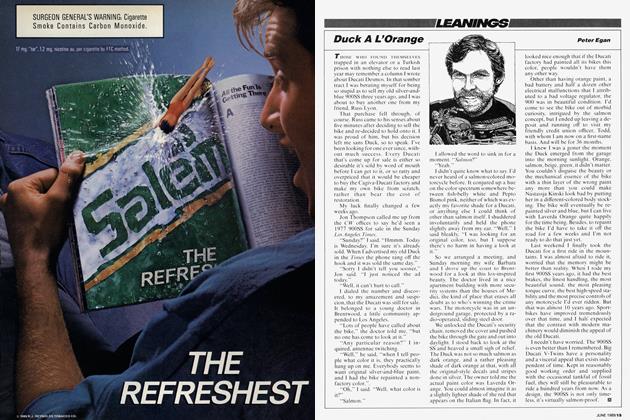

So that left privateer John Ashmead as the survivor, and the winner of Daytona 1989. Now, you need to understand that Ashmead is a veteran racer who has been a top runner in endurance and Superbike races for lO years. Back in 1985 his career looked like it was ready to take off when he won the Laguna Seca Superbike race. But a crash in the 1987 Trans-Atlantic Match Races was a setback that he never truly made a comeback from. Since then. Ashmead has been a consistent but unspectacular finisher in AMA Superbike racing. He was 12th in the l 987 championship and sixth in 1988. He crashed hard at Sears Point near the end of last year, breaking a number of bones, but he put together a Daytona effort anyway. He showed up on his battle-worn l 986 VFR750—number 22 off Honda’s assembly line— and nobody, least of all Ashmead himself, expected him to win. In fact, Ashmead didn't know' he had won when he crossed the finish line. He saw his number on top of Daytona’s electronic scoreboard and figured it was a mistake. “I thought I was in second,” he said, delighted by his own mistake.

Oddly enough, a lot of other riders were delighted by Ashmead’s win. Even second-place James. “It couldn't happen toa nicer guy,” said James. When you’ve ridden as long and hard, and paid as many dues as Ashmead has, they all felt, you deserve to w in. So Ashmead popped the cork on the biggest win of his life and sprayed champagne all over an equally disbelieving crowd in the the happiest moment in a long racing career.

And that, as much as any other part of Daytona 1989. is racing.