Cilpboard

RACE WATCH

Gadson shifts gears

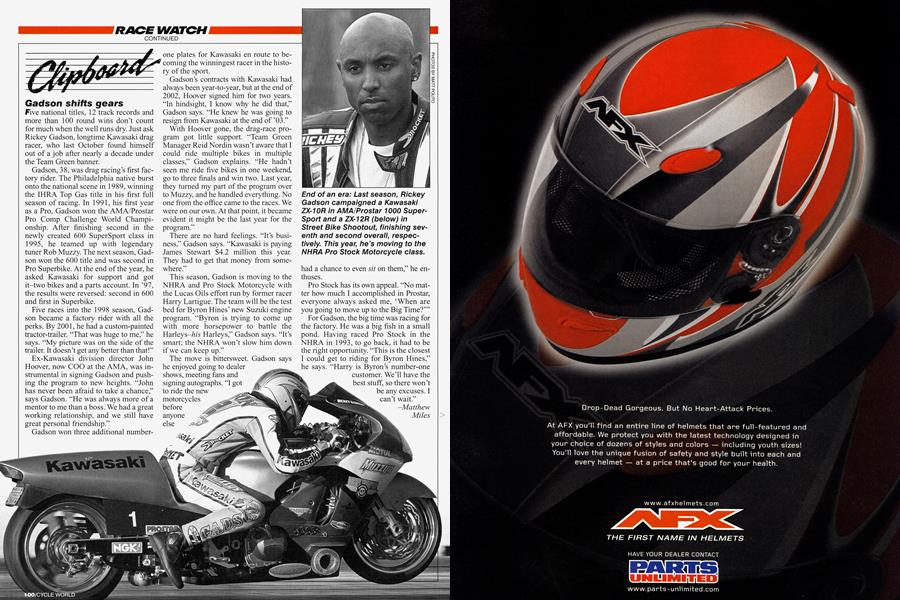

Five national titles, 12 track records and more than 100 round wins don’t count for much when the well runs dry. Just ask Rickey Gadson, longtime Kawasaki drag racer, who last October found himself out of a job after nearly a decade under the Team Green banner.

Gadson, 38, was drag racing’s first factory rider. The Philadelphia native burst onto the national scene in 1989, winning the IHRA Top Gas title in his first full season of racing. In 1991, his first year as a Pro, Gadson won the AMA/Prostar Pro Comp Challenge World Championship. After finishing second in the newly created 600 SuperSport class in 1995, he teamed up with legendary tuner Rob Muzzy. The next season, Gadson won the 600 title and was second in Pro Superbike. At the end of the year, he asked Kawasaki for support and got it-two bikes and a parts account. In ’97, the results were reversed: second in 600 and first in Superbike.

Five races into the 1998 season, Gadson became a factory rider with all the perks. By 2001, he had a custom-painted tractor-trailer. “That was huge to me,” he says. “My picture was on the side of the trailer. It doesn’t get any better than that!”

Ex-Kawasaki division director John Hoover, now COO at the AMA, was instrumental in signing Gadson and pushing the program to new heights. “John has never been afraid to take a chance,” says Gadson. “He was always more of a mentor to me than a boss. We had a great working relationship, and we still have great personal friendship.”

Gadson won three additional numberone plates for Kawasaki en route to becoming the winningest racer in the history of the sport.

Gadson’s contracts with Kawasaki had always been year-to-year, but at the end of 2002, Hoover signed him for two years. “In hindsight, I know why he did that,” Gadson says. “He knew he was going to resign from Kawasaki at the end of ’03.”

With Hoover gone, the drag-race program got little support. “Team Green Manager Reid Nordin wasn’t aware that I could ride multiple bikes in multiple classes,” Gadson explains. “He hadn’t seen me ride five bikes in one weekend, go to three finals and win two. Last year, they turned my part of the program over to Muzzy, and he handled everything. No one from the office came to the races. We were on our own. At that point, it became evident it might be the last year for the program.”

There are no hard feelings. “It’s business,” Gadson says. “Kawasaki is paying James Stewart $4.2 million this year. They had to get that money from somewhere.”

This season, Gadson is moving to the NHRA and Pro Stock Motorcycle with the Lucas Oils effort run by former racer Harry Lartigue. The team will be the test bed for Byron Hines’ new Suzuki engine program. “Byron is trying to come up with more horsepower to battle the Harleys-/?A Harleys,” Gadson says. “It’s smart; the NHRA won’t slow him down if we can keep up.”

The move is bittersweet. Gadson says he enjoyed going to dealer shows, meeting fans and signing autographs. “I got to ride the new motorcycles before anyone else had a chance to even sit on them,” he enthuses.

Pro Stock has its own appeal. “No matter how much I accomplished in Prostar, everyone always asked me, ‘When are you going to move up to the Big Time?”’ For Gadson, the big time was racing for the factory. He was a big fish in a small pond. Having raced Pro Stock in the NHRA in 1993, to go back, it had to be the right opportunity. “This is the closest I could get to riding for Byron Hines,” he says. “Harry is Byron’s number-one customer. We’ll have the best stuff, so there won’t be any excuses. I can’t wait.”

Matthew Miles

Six hours of “Funtana”

“How would you like to spend Saturday afternoon racing around California Speedway on a ZX-1 OR?” That was the question posed to me by my friend Jeff Hoeppner, who works for Kawasaki’s accessory division. Why not, I thought? Is there any better way to test future race-kit parts than to participate in a six-hour endurance race? Let the good times roll...

Hoeppner has done some endurance racing in the past and told me a bunch about the old Ontario Six-Hour, its geographical relationship to California Speedway and all the big names that participated in the race. These days, “Heppy” keeps his skills sharp racing a KX250F in Supermoto competition, so I was pretty sure we’d make a formidable pairing. We also drafted another Kawasaki employee, Jeff Herzog. The two Jeffs fought shoulder-to-shoulder on Ninja 600s in club events back in the day.

Cycle World has done its share of endurance racing over the years, too. Exstaffer Doug Toland, now with American Honda, is a former World Endurance and AMA Superteams Champion. Road Test Editor Don Canet won a WERA Endurance title with Team Valvoline Suzuki, run by ex-CW staffer John Ulrich, himself an accomplished racer. Editorin-Chief David Edwards, Executive Editor Brian Catterson and Editorial Director Paul Dean also have demonstrated their on-track staying power over the years. But it was Ulrich’s 1979 feature, “Lessons from the Six-Hour,” that detailed how endurance races could be used as the ultimate acid test for wringing out a magazine testbike.

To arrange for tires, I called upon another former CW staffer, Ken Vreeke, now handling Dunlop’s PR. “I’d be glad to help,” he told me. “I got my start at Ontario.” Vreeke called Dennis Smith of Sport Tire Services, who agreed to outfit our bike with 208GPs. Smith is another ex-endurance racer. In 1980, he teamed with Reg Pridmore to finish third overall behind Ron Pierce/Freddie Spencer and Dave Aldana/Eddie Lawson at the final Ontario Six-Hour. He also won three Willow Springs 24-Hours.

We used a Track Club track day at Laguna Seca to shake down the bike, and got it working pretty well. Just in time for the race, Hoeppner installed a Penske 8900 Series shock and a larger-thanstock 190/65-17 rear Dunlop. Using the larger tire required moving the wheel back, which lengthened the wheelbase and dramatically changed the bike’s handling characteristics. That gave us a lot to think about during Friday’s practice.

First time out, the bike felt like a cross between a pogo stick and a rocking horse; riding it for six hours would be hell. Suddenly, the brand-new bike we were so excited to ride wasn’t looking so hot! By the last session, however, we’d made lots of progress. Unfortunately, our smiles soon turned to frowns when Hoeppner came coasting down the front straight with a dead motor.

Back in our garage, he said, “It just lost power.” Restarting the engine resulted in a terrible “rackety-tackety” sound. Was it a valve? Camchain? Clutch-basket? Turns out Hoeppner, who is used to a reverse shift pattern, had accidentally backshifted from second to first gear when exiting the second chicane. As a result, the magnet in the trick gear-driven generator that spins at twice crank speed went south, tearing up the windings on its way. Oops! Luckily, Hoeppner had another ZX10R at his disposal. We worked quickly, swapping the street stuff for race riggings. Before we retired for the evening, we were back in business.

On Saturday morning, Herzog headed out to scrub in tires and bed in new brake pads. Hoeppner did the same in a later practice, just in case of a red-flag restart. The notion of charging into decreasingradius Turn 1 on brand-new tires wasn’t enticing. Climbing off the reconstructed ride, he pulled off his helmet, revealing a wide smile. Everything we’d done, setup-wise, had given us a competitive mount for the race ahead.

I started the race from 14th on the grid. When the green flag dropped, I did my best to get to the front. By the end of lap one, riding as if it were the only one that counted, I was up to fourth, only to give up a couple of spots when the oversprung Penske gave my spine a shock coming off the banking entering the Turn 1 chicane.

In the following laps, a duel arose between another rider and myself. Our lines must have intersected at least three times each lap! After 20 minutes of this tumultuous tomfoolery, the start-line amperage decreased enough that I remembered there were still 30 minutes remaining in my stint. So I settled into a consistent pace that would get us to our first pit stop.

The first rider change saw Hoeppner get away without a hitch. Both bike and tires were working well. We had the tools. It was up to us. At the halfway point, we changed the rear tire, going one stop further before swapping fronts. The latter change took way too long when one of the brake pads came adrift.

Forty-something Herzog paced himself during his last stint, but the heat and pressure were getting to him. He conserved his strength, burned through most of a tank of fuel and put us another hour down the road. Then, with 12 minutes to go in his session, he was saved by a red flag. Unfortunately, between the 8-minute front-tire fiasco and Herzog’s heat-stroke laps, Team Cycle World went from leading the Open Superstock class and sixth overall to down two laps and 12th overall. Not good.

At the restart, Hoeppner put in a hard pace, eventually passing the Open Superstock leader before petering out and pitting early. That left me charged with the final stint plus some. At the time, I didn’t know where we stood, but the dash-mounted clock told me there were just 18 minutes remaining in the race. In what seemed like only moments later, out came the white flag, which was followed by every racer’s favorite: the checkers. Much to our surprise, we ended up second in class and 10th overall. Not bad for a first-time effort!

Over the years, I’ve raced in a lot of club events, competed in AMA 600cc Supersport and 750cc Superstock, and even raced at the Isle of Man. I thought I knew a thing or two about racing. But endurance racing has shown me another all-new facet of bike riding: patience.

Mark Cernicky

Neil Hodgson: Coming to America m 2005

AMA Superbike is about to get a shot in the arm and a chance to gauge its worldwide competitiveness. This coming season, former British and World Superbike Champion Neil Hodgson will pair up with Eric Bostrom on factory-backed Ducatis.

Hodgson is an ex-motocrosser who began racing when he was just 9 years old. After breaking his leg at age 15, he decided he’d had enough of the dirt and turned to roadracing. He won the British 125cc title when he was 18, and then went straight to Grand Prix. A big lad on a tiny privateer bike, Hodgson battled first in the manic 125cc class, later on privateer 500s. Then came the first of many calls from Ducati.

“I’d always raced two-strokes, then I got a great opportunity in World Super-

bike,” he says. “Problem was, my firstever Superbike ride was a factory Ducati teamed with reigning World Champion Carl Fogarty! I was 21, a young kid given a fantastic opportunity, and I wasn’t ready. Instead of it taking me a couple of years to really get the hang of riding a heavy four-stroke, it took me four. By then, I’d been given my chance and got kicked out.”

Hodgson found himself back in England in British Superbike. “Then, everything started to go good,” he says. The 2000 season was arguably the hardestfought in series history. Hodgson came out on top, and won the respect and admiration of everyone in British racing and an opportunity to move back onto the world stage.

After two more years in WSB battling with Troy Bayliss, Colin Edwards and Ben Bostrom, Hodgson was once again signed to ride a factory Ducati. In 2003, the 999’s debut season, he won 13 races and his first world title. With champagne still stinging Hodgson’s eyes, MotoGP’s satellite D’Antin team came knocking with the promise of a year-old Desmosedici. But the ’04 season turned out to be a complete disaster.

Hodgson’s lap times at most tracks mirrored those posted the previous season by factory Ducati riders Troy Bayliss and Loris Capirossi, but even the slower teams had made progress in the off-season. As a result, his best finish was eighth in the crash-strewn Japanese GP at Motegi.

“Toward the end of the year, it was nearly impossible to get motivated,” Hodgson says. “After each event, I would go home feeling pretty down, have two weeks off, go cycling, re-motivate myself and feel positive. Then, on the Wednesday before the race, I’d meet my chief mechanic, who would tell me that no one had been paid, and that we were going to have to run the engine we’d already had problems with because we didn’t have a new one. I thought, ‘What am I doing here?”’ Hodgson is in no rush to go back to MotoGP. “Unless you’re in one of the top teams, you haven’t got a chance,” he says. “If you haven’t got a chance, why do it?”

But one tough season wasn’t about to derail the 31 -year-old Isle of Man resident. Again, Ducati called, this time offering either WSB or AMA.

“I’ve always thought it would be cool to race in America,” Hodgson admits. “I like the country. I’ve always watched the AMA championship on TV, and I like the look of the tracks. Also, the racing is always really close.

“The aim is to win the title,” he continues. “If it weren’t, I’d be conning Ducati and myself. That doesn’t mean I don’t realize what’s ahead of me. I expect it to be my hardest season ever. It’s not often someone comes into a championship, learns the tracks and wins the title, but it is possible and that is my goal.”

Gary Inman

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAussie Rules

March 2005 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsOn the Trail of the Mighty One

March 2005 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCTelephone Teams

March 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

March 2005 -

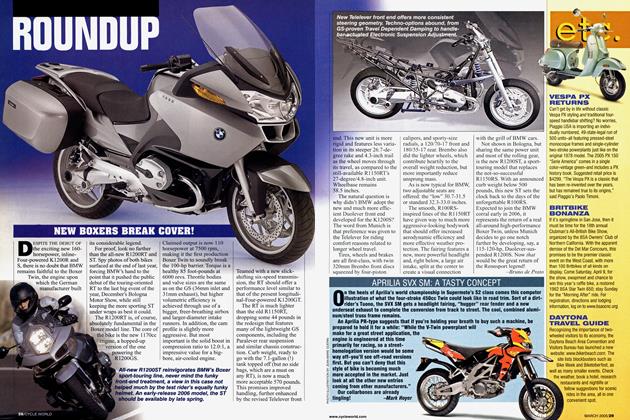

Roundup

RoundupNew Boxers Break Cover!

March 2005 By Bruno De Prato -

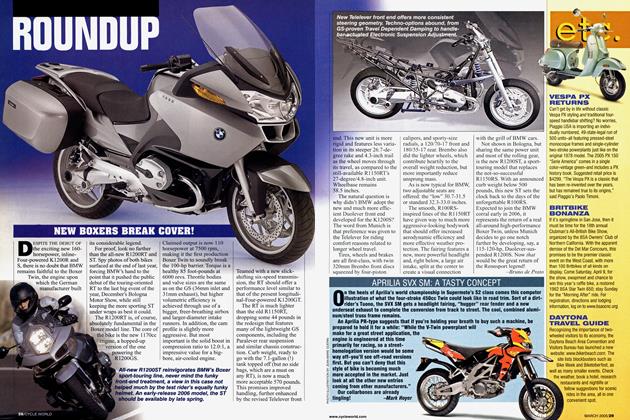

Roundup

RoundupAprilia Svx Sm: A Tasty Concept

March 2005 By Mark Hoyer