Telephone teams

TDC

Kevin Cameron

MTUCH-DISCUSSED IN AUTOMOTIVE CIR-cles is the idea of “virtual corporations.” Instead of pursuing the old Henry Ford model of a company that owns everything from iron mines to dealerships, and carries out all operations in between, the virtual corporation would own almost nothing.

Managers would hire consultants to plan and then design products. A quartermaster and scheduling firm would orchestrate the necessary parts from specialist suppliers in many countries. The parts could arrive anywhere on Earth-Costa Rica, Malaysia or Iowa City, Iowa-and would then be assembled by a local firm into vehicles adapted and priced for each market.

In all of this globally coordinated action, the virtual corporation would, like a movie producer, simply make it happen. The “virtue of virtual” would be specialization. A firm in Northern Ireland making ECU-controllable failsafe electro-mechanical engine oil pumps would continually send its products all over the world, not sit idle for long periods waiting for a big order from one or two major domestic customers. It would thus quickly develop both technology and manufacturing/scheduling excellence. All the closefitted planning and exchange of specifications would take place over the Internet, which as we have all tired of hearing, makes all points on the planet “equidistant.”

It sounds lovely and we know that Japanese motorcycle producers are quickly moving parts production to China as a means of at least partly implementing something like this.

That part is business. What I’d like to think about is motorsport, where “virtual teams” appear to be a coming thing.

At first, I thought of these as “telephone teams,” because they are so often summoned into being by someone’s riffling through a Rolodex and making a few calls. And I thought of them as a U.S. phenomenon. Not so. They are worldwide, for the so-called “satellite teams” in MotoGP are often of this type.

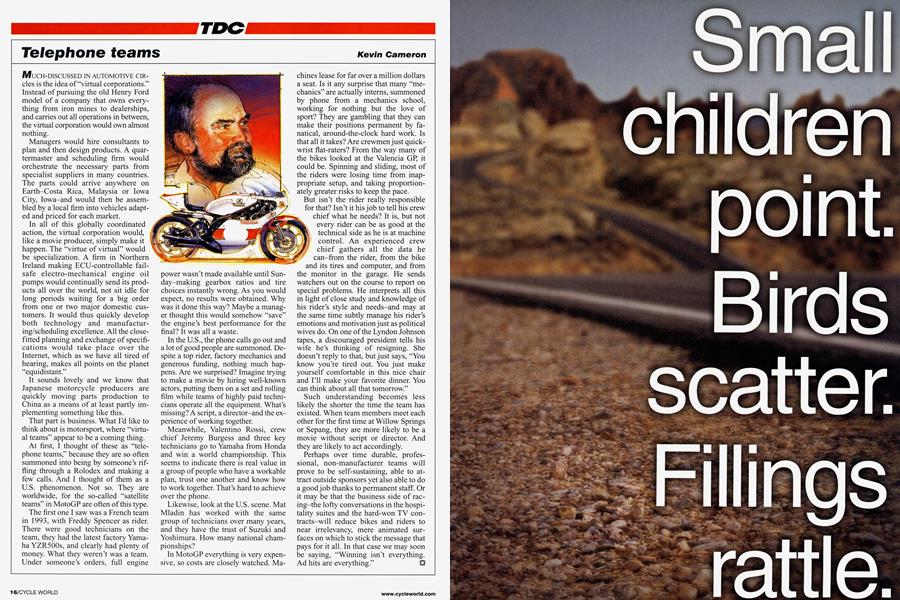

The first one I saw was a French team in 1993, with Freddy Spencer as rider. There were good technicians on the team, they had the latest factory Yamaha YZR500s, and clearly had plenty of money. What they weren’t was a team. Under someone’s orders, full engine power wasn’t made available until Sunday-making gearbox ratios and tire choices instantly wrong. As you would expect, no results were obtained. Why was it done this way? Maybe a manager thought this would somehow “save” the engine’s best performance for the final? It was all a waste.

In the U.S., the phone calls go out and a lot of good people are summoned. Despite a top rider, factory mechanics and generous funding, nothing much happens. Are we surprised? Imagine trying to make a movie by hiring well-known actors, putting them on a set and rolling film while teams of highly paid technicians operate all the equipment. What’s missing? A script, a director-and the experience of working together.

Meanwhile, Valentino Rossi, crew chief Jeremy Burgess and three key technicians go to Yamaha from Honda and win a world championship. This seems to indicate there is real value in a group of people who have a workable plan, trust one another and know how to work together. That’s hard to achieve over the phone.

Likewise, look at the U.S. scene. Mat Mladin has worked with the same group of technicians over many years, and they have the trust of Suzuki and Yoshimura. How many national championships?

In MotoGP everything is very expensive, so costs are closely watched. Machines lease for far over a million dollars a seat. Is it any surprise that many “mechanics” are actually interns, summoned by phone from a mechanics school, working for nothing but the love of sport? They are gambling that they can make their positions permanent by fanatical, around-the-clock hard work. Is that all it takes? Are crewmen just quickwrist flat-raters? From the way many of the bikes looked at the Valencia GP, it could be. Spinning and sliding, most of the riders were losing time from inappropriate setup, and taking proportionately greater risks to keep the pace.

But isn’t the rider really responsible for that? Isn’t it his job to tell his crew chief what he needs? It is, but not every rider can be as good at the technical side as he is at machine control. An experienced crew chief gathers all the data he ? can-from the rider, from the bike and its tires and computer, and from the monitor in the garage. He sends watchers out on the course to report on special problems. He interprets all this in light of close study and knowledge of his rider’s style and needs-and may at the same time subtly manage his rider’s emotions and motivation just as political wives do. On one of the Lyndon Johnson tapes, a discouraged president tells his wife he’s thinking of resigning. She doesn’t reply to that, but just says, “You know you’re tired out. You just make yourself comfortable in this nice chair and I’ll make your favorite dinner. You can think about all that tomorrow.”

Such understanding becomes less likely the shorter the time the team has existed. When team members meet each other for the first time at Willow Springs or Sepang, they are more likely to be a movie without script or director. And they are likely to act accordingly.

Perhaps over time durable, professional, non-manufacturer teams will prove to be self-sustaining, able to attract outside sponsors yet also able to do a good job thanks to permanent staff. Or it may be that the business side of racing-the lofty conversations in the hospitality suites and the hard-won TV contracts-will reduce bikes and riders to near irrelevancy, mere animated surfaces on which to stick the message that pays for it all. In that case we may soon be saying, “Winning isn’t everything. Ad hits are everything.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue