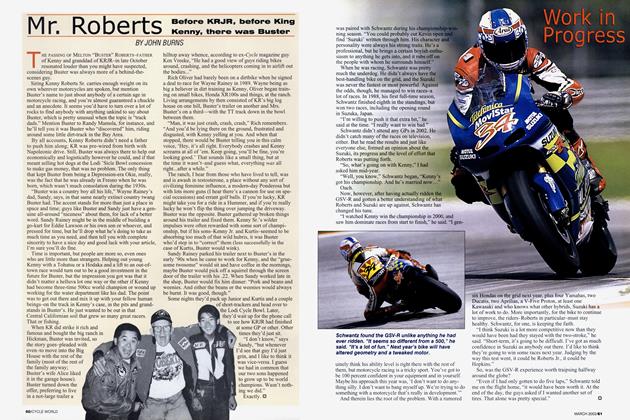

FOG MA CHINE

MARK FORSYTH

I KNOW, I KNOW, I AM VERY LUCKY. RIDING YOUR mate's RC5 1 down the bypass is one thing, but being one of the first to shakedown a brand-new racing Superbike is quite another. Not only have I ridden Carl Fogarty's Petronas FP1 at Germany's Eurospeedway circuit, I spent three whole days huddling with the team. From initially knowing just a little about the whole project, I now feel well-placed to say I know more than I probably should.

Probably should? Yes. I’m reading the non-disclosure agreement I signed in the pit garage, and behind all the solicitor-speak in impenetrably small print, it appears that I’m not allowed to tell you anything at all other than that the bike is the most beautiful shade of green, that the food at the hotel was more than adequate and that the weather in the former East Germany-nearly Poland, actually-was unexpectedly clement for the time of year.

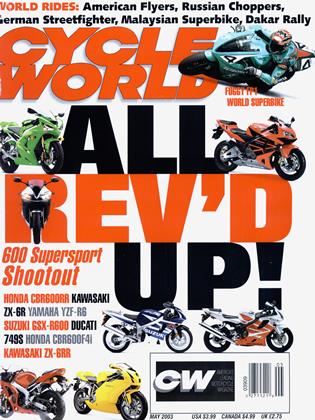

But what the hell, in the case of the influential and omnipotent Cycle World magazine, I’ll now blow the whistle and tell you the facts about the Foggy FP1 as it’s readied for battle on the 2003 World Superbike circuit.

The team was in Germany last November for a number of reasons, but most of them were intertwined with the need to rack up miles. This applies to track-rusty riders as much as to technicians who need to absorb and digest as much information as possible. This information only comes about with serious mileage at race (or near-race) pace.

If, as a brand-new WSB team, you buy a squadron of 998s from Ducati Corse, say, a book seven feet thick tells your crew how many racing miles a component will last before it needs checking or replacing. With amusingly translated Italian to English, this data-amassed over a racing decade plus four-predicts which fastener will come loose on which lap, and when the crank main journals are sure to make grumbling noises to within .3-mile. My point? Track experience is everything. However, with the Foggy FPl-a clean sheet of paper and a germ of an idea less than 12 months before-this gathering of data and information is an ongoing process. A whopping task. What this group of people has done in less than a year is nothing short of incredible. And what lies ahead is going to be equally tough.

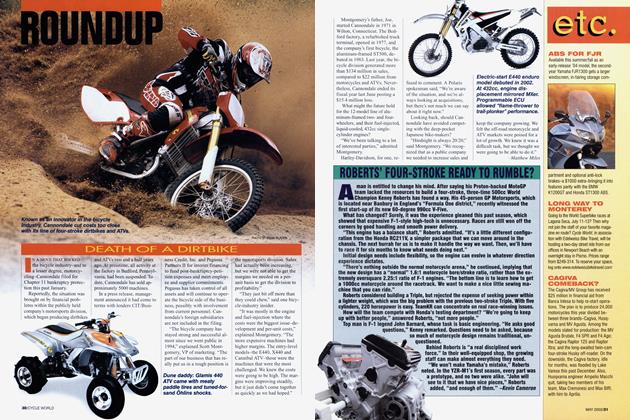

But the team hasn’t exactly happened by accident. The most impressive thing from three days kicking around the garage, waiting, waiting, waiting for the right moment to ride the beast, was just how vast the team’s amassed experience is. Foggy needs no introduction. Apparently well looked after by Ducati, but bored following his 2000 retirement, King Carl was enticed into spearheading this effort, bankrolled by Malaysian oil/gas-giant Petronas. Fogarty and team manager Nigel Bosworth then cherry-picked some of the best personnel from Grand Prix, World Superbike and British Superbike. It’s not so much a new team from scratch as a reunion of old and trusted, respected and revered friends-guys who wouldn’t buckle under severe pressure and a task bigger than the building of the Egyptian pyramids. Be it at the dinner table after a long day’s graft, in the pits after massive disappointment, or first thing in the morning after a very late night previous, the team is most definitely one unit. Without this essential quality, the project would be fundamentally flawed.

We arrive at the track in our VW Golf rental car-no stranger to its rev-limiter in the hour or so from Berlin airport-to discover not only one of the seven wonders of the East German civil engineering world (the Lausitzring facility is gob-smackingly vast and opulent), but to a somewhat strange atmosphere in the garage. The team’s number-two rider, 28-year-old James Hay don, former British Superbike pilot, is, as usual, firing on all 10 of his eight cylinders and giving life and his test program 110 percent. In the other half of the vast garage, the more worldly-wise (and, indeed, more World Championly-wise) Troy Corser looks like he’s got something bothering him. Troy, it transpires, is experiencing great success gathering data on just how long certain components last before they go “pop.”

By lunchtime on day one, things are cheering up in the left-hand side of the garage as Corser’s spare bike is readied for yet more laps and yet more abuse. Haydon’s perma-grin is hard to de-tune, and he just does lap after lap on a bike that’s racking up the miles like a hard-pressed London cab. According to Haydon’s technician “Zim” (he’s from Zimabwe), this bike may not be as fast as they want, but it’s racked up nearly 200 miles with no problems whatsoever. With Hay don at the controls, a man who is definitely not familiar with tickover, this is something of a major result.

There have been engine failures, or rather engine-component failures, but who in their right mind wouldn’t expect that? This isn’t the 989cc F-l-inspired MotoGP engine originally designed by Sauber Petronas Engineering, it’s a brand-new 900cc WSB’ed version of the “reverse” inlineTriple (intakes facing forward, exhausts straight out the back), and a scratch-built powerplant at its first real test is going to experience problems. That’s why, after all, we’re here. Get the miles in, run it round the block and see what falls off. To me, a hardened hack stood in the background watching all, reliability is almost disappointingly good.

By day two a new engine arrives, delivered by Eskil Suter himself. The Swiss-based ex-250cc GP rider is handling engine development for the FP1 racebikes and the 75 street examples required for homologation. Impressively, he brings Corser’s new motor as airline hand luggage in a big cardboard box full of polystyrene chips. Stickers on the box say “37 kgs,” “This way up” (to avoid oil spillage on passengers’ raincoats?) and, alarmingly, “Fragile.” As a measure of workflow, Lofty and Sean, the team’s drivers, load their Opel up with five used motors to return to Suter’s shop the same evening. The dedicated duo drive through the night to Stuttgart, only to break down somewhere in mid-Gemany at 11 p.m. Regardless, they make the drop and return to the circuit, bleary-eyed but cheerful at 11 a.m. the following morning. Sadly for the team, their rental car is empty on its return.

Loads of engines is what they want and need at this stage.

Troy’s spare bike is stronger. Much stronger. He posts his fastest lap of the test on a track visibly dirty and 59 degrees cool. Optimism rears its ugly head, but it’s short-lived; misfortune head-butts it back into place. Corser’s engine fails.

He felt it tightening and whipped the clutch in, saving a heap more carnage. Now, several hundred miles down the line, the team knows how many hours a certain component will last before it needs changing. They work way into the evening to fit a fresh motor. You’d expect a black cloud over the proceedings-far from it; there’s visible optimism, a good degree of banter and a large amount of laughs. Bearing in mind the lap times today, things are looking up. No amount of swarf in the sump pan can quench the garage spirit.

By day three, even Corser is cracking a smile. There’s no knocking it, the chassis and geometry are stunning, and the Foggy Petronas FP1 is almost GP-good in terms of feel and behavior. Troy and the rest of the team know that engine development is the biggest task ahead and, for a man used to instant success, almost guaranteed results and Monacoresident spoils of victory, he is clearly riding the bumpy roller-coaster of emotions. But the 31-year-old has faith.

“If it was Joe Blow doing this project, I wouldn’t have given it a second look,” Troy says, oblivious to Joe Blow’s feelings. “But I know Carl wants the best out of everything, and so do I.”

Between engine urps, what does Corser see as the FPl’s strongest points so far?

“Got to be the chassis and the aerodynamics,” says the former factory Ducati and Aprilia star. “Where the 916 was styled for looks first, the Foggy FPl has been designed to be slippery and look good, too. It changes direction better than the 916, I’d say, and has real strong mid-comer speed.

It feels really well-balanced; it surprised me it didn’t push wide (exiting comers). That’s the first problem I look for in a bike, and it was right first time out.”

Predictions for the season?

“I guess I’d look for top-10s early on and podiums toward mid-season,” Corser says confidently.

Finally, despite the rain, the track and the bike are mine.

“Watch out for the track driers, though,” warns Bosworth, mindful of the damage that a jet engine mounted on the back of a pickup truck can do to an irreplaceable motorcycle.

Never before have I left a pit garage, any pit garage, so aware of everyone watching my every movement. This is not a time to select a false neutral, to stall the motor or to lose your footing on the garage’s snap-together plastic flooring. Gulp. Let the revs drop.. .coax it into first.. .(think)... one up, click...

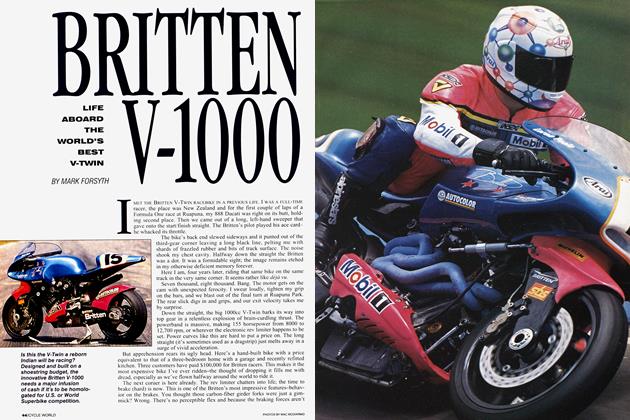

A quick squirt down pit lane-after all, it’d be rude not to-and acceleration through the first three closely ratio’ed gears is front-wheel-loftingly brisk. You’d expect no less. And the noise? Fan-bloody-tastic! Sharp-edged induction rasp and a cacophony of straight-cut gear backlash and whine echo off the massive covered grandstands. This is the sound of exotica. I make a mental note to pinch myself. Maybe later, though.

The riding position, that crucial triangle of dimensions between bars, seat and footrests, feels just like my only other WSB yardstick, the Ducati 998 I rode last season. Like the benchmark Ducati, the Foggy FPl feels much smaller than it should. It’s narrow, tightly waisted and feels easy to wrestle around. Weight is bang-on the 356-pound limit, including all the data-logging equipment.

The dimensions and lack of flab may be heavenly, but the track is a total nightmare. I’ve got a brand-new cut slick in the front that’s shinier than a Hollywood grin and the track goes from wet to patchy to just plain kebab-greasy. But if nothing else, it gives me some insight into how easy the Foggy FPl is to position. At these teetering speeds, it steers like a trials bike, and will flick from side to side like one, too, through the Eurospeedway’s chicanes and tight turns.

After a few minutes, a dry line (albeit dotted with kerosene from the track driers) appears, and I can use the long straights and a couple of dry comers to give the FPl some proper throttle-cable-stretching berries.

Power happens, obviously, right from idle, but things start to go ballistic at 7 and then 10, eventually petering out at 14,500 rpm-a dizzy rev ceiling for a motor with a bore and stroke of 88.0 x 49.3mm. I just wish the printed medium you’re reading this on could do justice to the rasping, howling wail you hear when the motor comes on-song right under your chin. What you’ll hear trackside next season is a B-side flop compared to what the rider enjoys, believe me. In the motorcycle noises Top Ten, this would go platinum overnight.

Wide full open, everything gels nicely. The electric quickshifter allows rapid and positive selection of the next-taller

cog without the need to back off the gas. The revs barely drop between shifts, and the FPl fires itself and its hapless pilot toward the next unpredictably damp turn.

But small throttle openings are not so joyous. That sensitivity you look for when you’re sniffing for rear traction in the damp-the first crucial couple of degrees of twistgrip movement-is instead switch-like. The transition is far from progressive, which ain’t great on a circuit with no fast comers and, more importantly, no tmly dry ones. Rob Mathewson, the team’s fuel-injection (and ignition and gearbox and engine) expert, is fully aware of this idiosyncrasy.

“It’s all in the ignition curve and fuel delivery. It’s almost impossible to replicate this sensation on the dyno; it takes a rider to point it out. We know what’s causing it and it’s relatively easy to map out.” He says it so quietly and sincerely, I instantly believe him.

This is Haydon’s bike, and he’s been requesting more and more rear ride height as the test progresses in an attempt to get more weight over the front tire’s contact patch. The side effect of this catches me out on my first fast mn into Turn 9.1 sit up, grab enough front brake to scrub off the desired amount of speed and the back end slews sideways as I snick down through the gears. Whoa!

I make a mental note not to do it again.

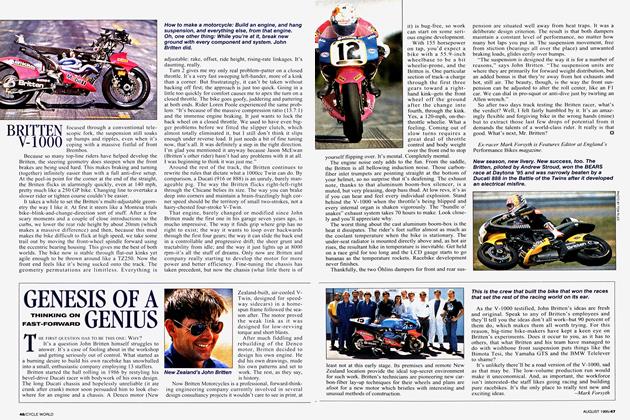

There is a bewildering but cmcial amount of adjustment everywhere on the FPl-from the patented rake-altering mechanism and oh-so-simple trail adjustment to the varying-thickness seat units that double as tunable torsional stiffeners. The whole chassis is fantastically right straight from the crate, a work of art. You think the FP1 looks beautiful with its bodywork on, but it gets prettier the more you remove.

My seat-of-the-pants dyno, finely tuned by nearly 14 years of practice, estimates peak power on this far-fromffesh engine to be around 150-160 bhp (compared to a factory-fresh RC51’s 180). But Triples, like Twins, are funny and often deceptive beasts, delivering their thrust in mysterious ways, so maybe my leather pants are mistaken. It’s a waste of time asking the riders if it needs more power and acceleration because racers always want more.

Says Bosworth, “The key to all engine design is time. We didn’t expect to be here so soon. The last thing we wanted in these early days of testing was huge power but massive unreliability. This motor has true race-ready potential.”

This comes from a man responsible for a team of people who have their hands on the latest and most powerful predictive computer programs. They know where the extra horses lie. It’ll come in time.

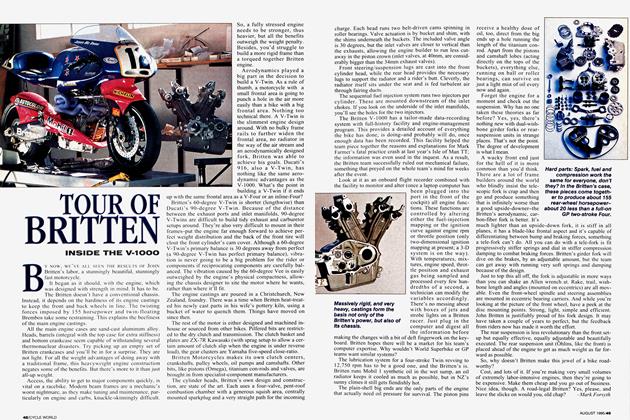

My ride’s over sooner than I’d wished, but time, as they say, flies when you’re ’avin’ it large. I feel privileged to have been able to swing a leg over the Foggy FP1, and in effect become the fourth rider in history to do so after Corser and Haydon-and Foggy himself, of course. At this particular juncture, I’d like to put my name forward to ride it again when the team has completed an arduous winter of testing and round-the-clock development. Can we have some sun next time, please, fellers? U

Freelance journalist Mark Forsyth was editor at England ’s Performance Bikes from 1995-97. His racing résumé includes the 1989 British Battle of the Twins Championship and a 600cc class win at the 1995 Bol d’Or endurance event. “At which point, ” he says, “I retired on the spot. ” Forsyth currently writes a motorcycle column for one of the U.K. ’s leading tabloid newspapers.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue