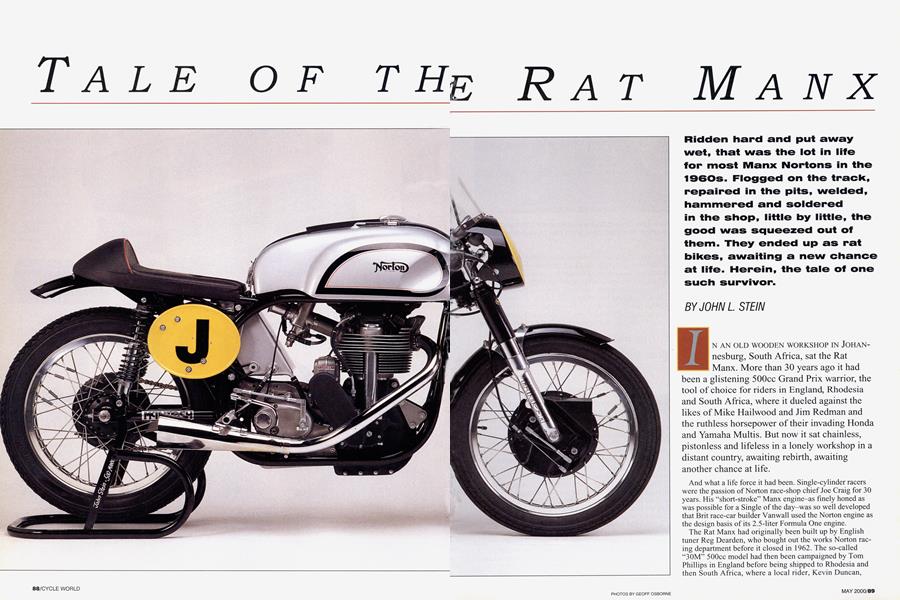

TALE OF THE RAT MANX

Ridden hard and put away wet, that was the lot in life for most Manx Nortons in the 1960s. Flogged on the track, repaired in the pits, welded, hammered and soldered in the shop, little by little, the good was squeezed out of them. They ended up as rat bikes, awaiting a new chance at life. Herein, the tale of one such survivor.

JOHN L. STEIN

IN AN OLD WOODEN WORKSHOP IN JOHANnesburg , South Africa, sat the Rat Manx. More than 30 years ago it had been a glistening 500cc Grand Prix warrior, the tool of choice for riders in England, Rhodesia and South Africa, where it dueled against the likes of Mike Hailwood and Jim Redman and the ruthless horsepower of their invading Honda and Yamaha Multis. But now it sat chainless, pistonless and lifeless in a lonely workshop in a distant country, awaiting rebirth, awaiting another chance at life.

And what a life force it had been. Single-cylinder racers were the passion of Norton race-shop chief Joe Craig for 30 years. His “short-stroke” Manx engine-as finely honed as was possible for a Single of the day-was so well developed that Brit race-car builder Vanwall used the Norton engine as the design basis of its 2.5-liter Formula One engine. The Rat Manx had originally been built up by English tuner Reg Dearden, who bought out the works Norton racing department before it closed in 1962. The so-called “30M” 500cc model had then been campaigned by Tom Phillips in England before being shipped to Rhodesia and then South Africa, where a local rider, Kevin Duncan,

finished second in the South African 500cc championship, a “winter” series of choice for Europeans. In the late Sixties, it wore a Rickman disc-brake setup as tuners sought to harness new technology from the car world. Rhodesia was something of a hotbed for roadracers at the time, producing such virtuosos as Ray Amm, Gary Hocking and Redman. “Bikes were hard to come by in Africa,” says Duncan Robertson, one of the Manx’s previous owners, “although there was keen interest in racing. It was quite

common for foreign riders to bring bikes with them when they came to race, then sell them before going home. It would help finance the trip.” Kevin Duncan campaigned the Manx long and hard, until it had been used up, blown up, bored out and used up again in an ultimately futile attempt to compete with faster machines, not the least of which was Hailwood’s works Honda 250 Four and Redman’s Yamaha RD56. Duncan sold it to another racer who sold it to Robertson, who rode vintage parades until the bike was too tired to run. Robertson then sold it to newspaper journalist John D’Oliveira, who had The Vision, but ran out of time. Before his death in 1987, D'Oliveira had planned to restore the Manx to ride during retirement. Which is where I come in. With help from D’Oliveira’s son, and restorer Chris Davies, arrangements were made for Singapore Airlines to fly the Rat Manx from J’burg to Singapore to Los Angeles. When the crate was pried open in May, 1998, it was like peering into a treasure-filled Egyptian tomb. In box after box were hundreds of alien parts and assemblies, leftover consumables of war: Crankpins, bearings, races and cages, cylinders, valves and springs, various shims, pins and cast-

progress hen the shipping crate from South Africa was pried open, it was like peering into a treasure filled Egyptian tomb. Box afer box of alien parts and assemblies, the leftover consumables of war...

ings were all packed around the Manx like possessions it would need in its next life. But there were problems, as I discovered when I turned the crankshaft sprocket. An unattached con-rod clanked inside an empty cylinder. Yes, the Norton was a rat-dirty, dusty and disheveled. It was also pregnant with promise. To achieve a strong-running vintage racer that adhered to the original spirit of the Manx meant keeping the 19-inch wheels, four-speed gearbox and chain primary drive, the usual casualties of progress as riders

try to improve upon the Norton’s performance. The second consideration was whether to focus on the mechanicals and leave the appearance scruffy, or to repaint, replate and restore. I picked up the phone and called Ken McIntosh in Auckland, New Zealand. McIntosh builds and rebuilds Manxes, new and old. The bike had already visited four continents. Why not a fifth? A strong U.S. dollar had a lot to do with the decision. Nearly two for one to the Kiwi dollar, my money would go farther at McIntosh Racing than any place I knew in America. I gulped, and shipped. McIntosh and his crew would turn the wrenches, I’d shag parts and send greenbacks. The scrounger part of my brain told me that all the Manx needed was a good hose-off, a piston and rings, a couple of chains, new tires and some bean oil. The wary part of my brain was shouting Chicken Little warnings. The truth was borne by McIntosh the day after the bike arrived. He announced good-naturedly, “I’ve called to tell you that we’ve found one part on your motorcycle that’s not buggered. It’s this tiny little screw...” McIntosh Racing’s Peter Welch is a toolmaker by training, and he approached the piecemeal engine with uncommon care and precision. And not a little bit of expertise: He’d built methanol-powered Manx engines for the likes of four-time

World Champion Hugh Anderson, who at 65 is still remarkably swift-he recently beat Barry Sheene and 40 Kiwi and Aussie riders to finish second in the 1999 Oceania Championship.

What McIntosh and Welch discovered was distressing. Besides the missing piston, the left-side magnesium engine case had a worrisome hairline crack and the cylinder head had been ported to match an earlier big-bore conversion. Neither would be useable for 500-class vintage duty.

Filing the unusable parts in a kind of “pedigree” box, McIntosh supplied a new magnesium crankcase half indistinguishable from the original. Ditto a new cylinder head, sand-cast to the original pattern. To make the motor run without “megaphonitis,” and still produce power at 8000

• esides the missing piston, the left-side magnesium case had a worrisome hairline • crack and the cylinder head had been ported to match an earlier big-bore con version. Neither would be useablefor 500-class vintage duty.

revs-a thousand higher than stock-McIntosh shaped the intake ports and fit a new exhaust pipe, and chose specific intake and exhaust valve sizes to match the Manx’s largerthan-stock 1 1/2-inch Amal GP carb.

Manx motors are similar in some ways to bevel-drive Ducati Singles. The overhead cambox is driven by a towershaft and bevel gears, all shimmed carefully and built up in an elaborate assembly. It takes lots of time to do right.

“The cases are strong enough,” McIntosh said. “It was the big-end bearing and piston that used to be the problem. We built the engine up with the strongest parts available: a special needle-bearing big-end, a Carrillo rod, a Cosworth piston and a titanium wristpin. Also, we used titanium valves so the topend will live if you miss a shift. Basically, we’ve kept with the spirit of the bike, but have taken steps to improve reliability where technology allows. At the end of the day, it doesn’t affect how they look or run that much, but it does affect how long they last. And if these improvements help people keep going on these bikes, then we’ve done something positive.”

Over the five months McIntosh had the bike, I’d received periodic progress reports coupled with requests for money-in the end, a five-figure bill. The engine castings were a straightforward matter. Harder to rectify was a problem with

the Manx’s unusual Lucas 2MTT double-spark magneto. The Manx’s cylinder head had been an experimental doubleplug unit, but the double-plug magnetos are notoriously unreliable, and so I began to search for the preferred singleplug “rotating-magnet” model. I called, faxed and e-mailed across at least three continents. “Oh, right,” they’d invariably answer, “I saw one of those about 20 years ago.” McIntosh finally agreed to convert an SR road magneto for the job.

Finding a replacement tachometer was easier. Dennis Quinlan in Australia bought out the Smiths Instruments rac-

ing shop. He uses genuine Smiths movements, complete with ball bearing-supported shafts, inside newly manufactured cast-aluminum cases.

Likewise, the fuel tank presented a worrisome problem, for both of the original tanks were badly damaged from years of abuse, and would likely fail at some point.

McIntosh sourced a tank from Steve Roberts, a former panel-beater for Aston Martin who now works in relative isolation. He only agrees to do a few tanks for McIntosh on the condition that no one bother him. Each new tank is hand-hammered to the exact original pattern, with surge baffles inside to stabilize the fuel load during braking. Roberts also rebuilt the original oil tank, the lower half of which had been hopelessly clogged by dirty oil residue.

I fly to Auckland in early 1999 to see the completed bike for the first time, and to race it in the annual Pukekohe Classic Festival. In its time away, the Rat Manx has become impossibly beautiful. It’s the essential motorcycle-the long, draping tank, positively swimming in silver paint that might just as well be liquid mercury, leads the eye to the intricate detail of the big engine. The bike sits regally on its stand, in the company of a dozen and a half other Norton racers, in the McIntosh shop. A Manx owner’s utopia.

The detailing is exquisite. It’s not something you could do on the first try, because trial-and-error assembly always extracts a toll on parts. This bike went together perfectly, but authentically. The only visual concessions to modem times are modem Koni shocks, one-size-wider 19-inch rims and sticky original-pattem Avon tires, all calculated to be legal in AHRMA’s Classic Sixties class.

It is 2:45 p.m. in Auckland on the Tuesday before the race meeting. Typical McIntosh, everything is just about buttoned-up and track-ready. Dave Kenah, Hugh Anderson’s mechanic for some 40 years, sets to work attaching the carb’s fuel-line banjo, just back from the plater’s. That done, McIntosh bungees on a license plate. Time for a test ride. I get on, engage first gear, and someone pushes me from the

back. The bike fires on the first try, with a very loud, staccato blast echoing from the baffled pipe. Its booming note makes the bike shudder in waves, with every part jittering and vibrating. The big flywheels help the bike move away and, amazingly, onto the public roads near the race shop. The thing vibrates like a jackhammer and obviously wants to rev, but the engine is tractable enough to deal with traffic. Yet this is no girlie-man bike. The seating position is very far aft, so it’s a long reach to the handlebars. It will take strong hands to hold onto them.

There’s a special language and a special set of skills needed for vintage racebikes. It’s language that has ceased to exist for those who ride modem bikes. That’s because instead of

tretched like a rubberband over the Norton~ 5-gallon gas tank, chin propped on a sponge pad,your eyes try to command a dancing, vibrating world Into focus as the machine tears a hole in the air at nearly 130 mph.

disconnecting you from the mechanical workings, the Manx takes you back to the essence of the machine. There is no operator’s manual for this bike. It is expected that you will know (or leam) the following: primary-chain tension; brake adjustment; carburetor tickling; backing up onto compression; TDC; bump-starts; jetting; dry-sump scavenging.

Much of this I know already, but I leam more, such as that you can tickle an Amal GP by just leaning the bike to the right and watching for a drip from the pilot air bleed. Or that backing the bike up on compression after mnning it relaxes the valve springs. Or that spokes on a conical-hub wheel feel looser on one side than the other. Or that Amal racing jets were flow-tested and are identifiable by the lack of grooves cut around their hex surfaces.

Come the weekend, I’m entered in five races for factorybuilt racers and one Manx-only event. In practice, the bike feels extremely stable but impossibly long and slow-turning. And the big tank prevents the rider from sliding up and weighting the front end. But as my speed builds, I begin to appreciate the stability more and more.

As noted, the big engine has a lot of flywheel effect, and so I upshift carefully, allowing the revs to drop before engaging the next gear. It indeed shows no sign of megaphonitis, just fluttering a bit at 7000 rpm. We drop the main jet one size after practice and the engine is spot-on.

The twin-leading-shoe front brake, carefully assembled and arced by Welch, is good but probably not in the same league as the four-leading-shoe dmm that Manxes wore in 1962, or as the Rickman disc this bike wore in South Africa. Racing will show whether there’s competitive stopping power for vintage battle. Lord knows it’s got motor. McIntosh dynoed it at 45.6 bhp at the back wheel. It’s not the 50-plus of the methanol-powered, shortpipe shop bikes, but it’s excellent for a gas-powered 30M-on the

same dyno, an original ’62 Manx delivered 40 bhp.

Pulling onto the track, that famous engine is alive down inside the frame cradle below you. It accelerates with a jangling fury, its flat, drone-like exhaust pulses gushing out of the big megaphone as the tach needle frantically dances past 7000 rpm. You make yourself into a tiny ball, tucking behind the slim numberplate and windscreen. Rap out first gear to 75 miles per hour. The huge flywheels keep spinning as you press down with your right foot for second, which delivers you to “the ton”-100 mph. Third gear brings 120. Stretched like a rubber band over the Norton’s 5-gallon tank, chin propped on a sponge pad, your eyes try to command a dancing, vibrating world into focus as the machine tears a hole in the air at nearly 130 mph.

The Rat Manx redeems itself. Against a fast crowd on the New Zealand vintage circuit-Anderson, 500cc GP veteran Ginger Molloy, BEARS world champ Andrew Stroud, Warren Marsh and McIntosh himself-it gamers one overall win, plus a second, third, fourth, fifth and sixth. Not bad for a former relic. And a great rebirth for the Rat Manx. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontFree Bikes And Other Myths

May 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsOpening the Eastern Gate

May 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCWorking All Night

May 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

May 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupTop Tourer? Honda Gl1800 Gold Wing

May 2000 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki Street-Traciker

May 2000 By Nick Ienatsch