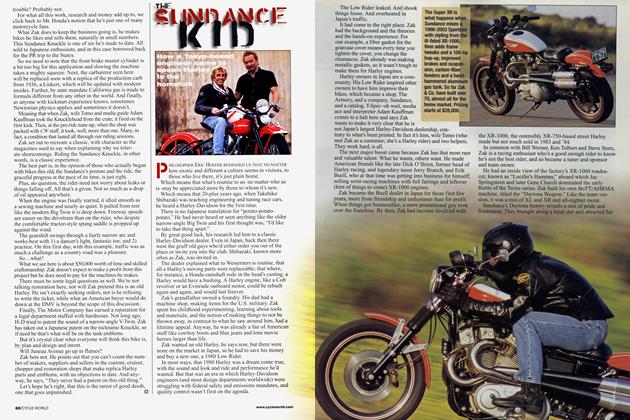

TOP FUEL COOL

In praise of JI~ nitro Sportster

COOK NEILSON

LET ME TELL YOU ABOUT NITROMETHANE. IT IS AN industrial solvent, clear, not particularly odorous in its lunburned state, reluctantly flammable. It weighs 9 1/2 pounds per gallon-about 60 percent more than gasoline-and it is 49.5 percent by weight pure oxygen. Its formula is CH3NO2. When properly mixed with tiny splashes of any number of compatible chemicals, presented in reasonable quantities to the combustion chambers of more-or-less ordinary engines, and decently ignited, it will produce double the horsepower of conventional gasoline.

A well-assembled nitro-burning engine has a cackle and roar to it, not to mention an eye-burning and nostril-shat tering in-your-face hyperkinetic immediacy, that a gaso line-fueled engine cannot hope to match.

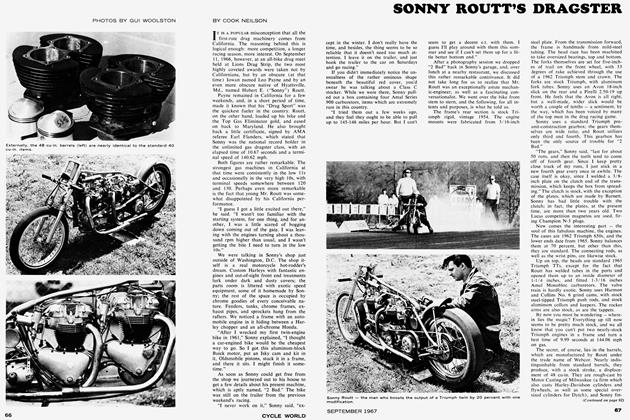

Through the latter part of the Sixties and into the early Seventies, a very particular motorcycling culture grew and thrived around this oddball chemical. Using more-or-less standard Harley-Davidson crankcases and easily obtained stroker crankshafts; chassis that ranged from lightly modi fied stock to custom-built magnesium and titanium confec tions; oversized and nitrided cylinders housing all different kinds of pistons; nothing particularly exotic by way of cylinder-head modifications; and a painfully crude yet wonderfully effective S&S carburetor, anybody who wanted to could build a Sportster good for quarter-mile ETs in the low 9s and trap speeds -pushing 160 mph.

Nitromethane-and one other chemical, I propylene oxide-largely made this engine performance possible. P0 was the juice that turned nitromethane into the golden-tressed engine-torching bitch goddess we all adored.

Throw a match into a little puddle of straight nitro and if you were lucky it would catch fire and burn with a faint, flickering blue-white glow. Add a few drops of P0 and try again: Now your little puddle goes off with genuine anger. So there wasn't much to the Sportster Top Fuel drag rac ers of the day, nor did there have to be. Until M&H came along with a 5-inch-wide slick, we were all perfectly happy with Avon's 4-incher, and any decent high-gear-only Harley could smoke the tire for close to the entire quarter-mile. If your bike was running well on any given day and you were sharp on the timing lights, you had as good a chance to win as anybody else-because fuel Sportsters were, for all intents and purposes, the same. The willingness of drag racers to share parts and information is folkioric-and true. What spares you brought became communal, whether you were in New Jersey or Florida or Illinois or California. Everybody knew everybody; almost everybody liked almost everybody. Even fuel mixtures were never the deep dark secret we all made them out to be.

I first gota sense of P0's character at Bonneville in 1969, when a guy tossed a cup of it into the air and nothing came down. The label on my very first can of the stuff identified it as a fumigant useful in the pre production of canned fruits and vegetables. Added in small percentages, it quelled nitro's inclination to pre-ignite while encouraging it to burn completely.

Compared to the racebikes of today, there was a wonder ful, spidery, almost lyrical simplicity to the fuel dragsters of 30 years ago. Characteristically, front ends were way out there, both to move the center of gravity back and to add, it was thought, more trail and thus high-speed stability. Tiny fuel tanks were either mounted on the frame's backbone or between the triple-clamps; similarly undersized oil reser voirs ordinarily were located just behind the rear cylinder. Fork assemblies, with or without brakes, came from every where, most notably H-D Sprint and Rapido models.

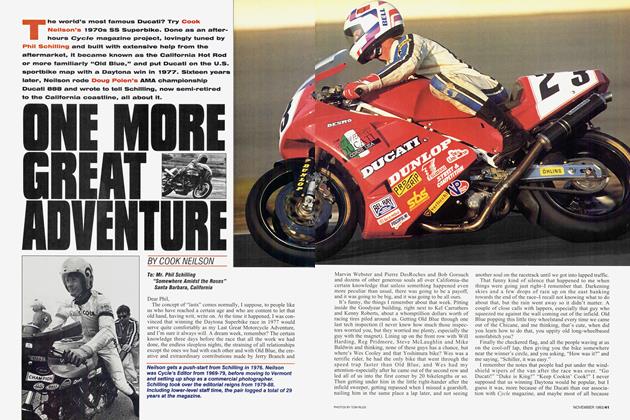

This openness goes back to the godfather of us all, a stumpy, quiet, powerful Iowan named Leo Payne (pictured, with the bubble visor). Leo invented the highgear-only nitro-burning Sportster around 1965 or 1966, and became famous when he took it to California and beat up on the leg endary twin-engined Triumph of Boris Murray. We Sportster peo pie followed his exploits in the drag-racing weeklies, and the more we found out about what he had done, the more plausible it became for us to try to do the same thing. We learned how he engineered high-gear-only, and the special thinned clutch plates that were integral to the concept. He and George Smith of S&S developed the mega-volume (main jet size: a 1/4-inch and up)

nitro carburetor. Leo took us from 1320 feet of tire-smoke to the much quicker slip-the clutch technique. Within two years, there appeared at dragstrips across the country at least a hundred Sportsters, all practically identical to Leo's, all mnning in the mid-9s at over 150 mph. For a year or two after

that, you could take your $2500 investment directly to the top of motorcycle drag racing's food chain, happily bending rods and blowing off cylinders with the best of them, and be com petitive. Your chances of lining up against Leo or Boris or Joe Smith or Sonny Routt in the finals at Indianapolis or Irwindale or Atco or Alton-and beating them-were just as good as anybody else's. Leo's Top Fuel Sportster-copied by all of us-was the Yamaha TD1 of its realm.

It couldn't last, this time of innocence, and it didn't. Inevitably, the technology pushed forward, taking many different forms: automotive-style slipper clutches, car sized rear tires, fuel-injection, supercharging, more exotic multi-engine rigs. Imagination and engineering progress yielded better times-guys were running in the 8s at well over 165 mph by late in 1971. But the number of Top Fuel racers who were truly competitive diminished, and the airy, delicate, magical little single-engined nitro-burning

Sportster, so big-voiced and so easy to ride and so much fun to be around, finally disap peared altogetheralong with the sweet tempered, close-knit fraternity that loved it.~

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

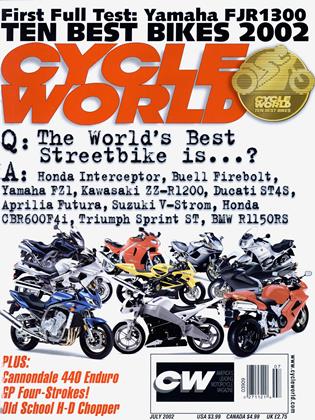

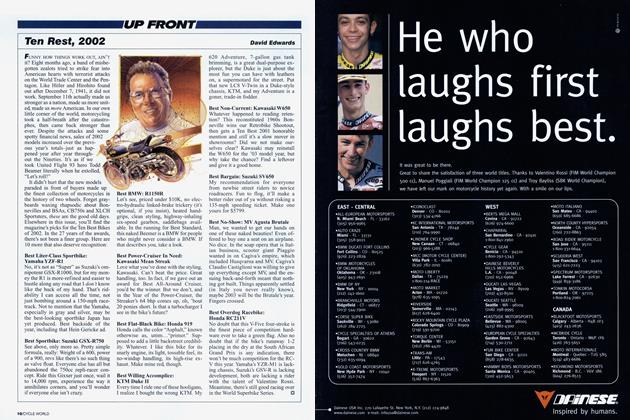

Up FrontTen Rest, 2002

July 2002 By David Edwards -

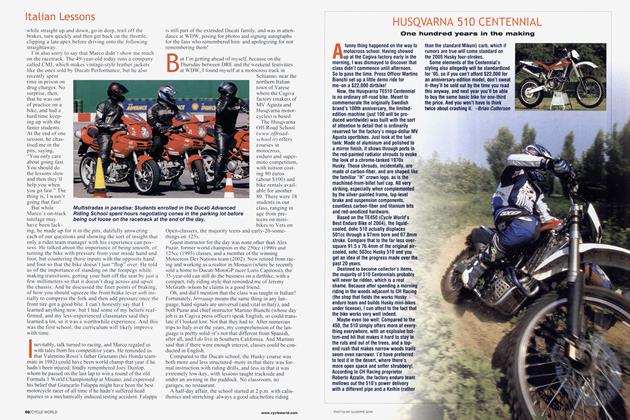

Leanings

LeaningsGreat Mysteries of Motorcycling

July 2002 By Peter Egan -

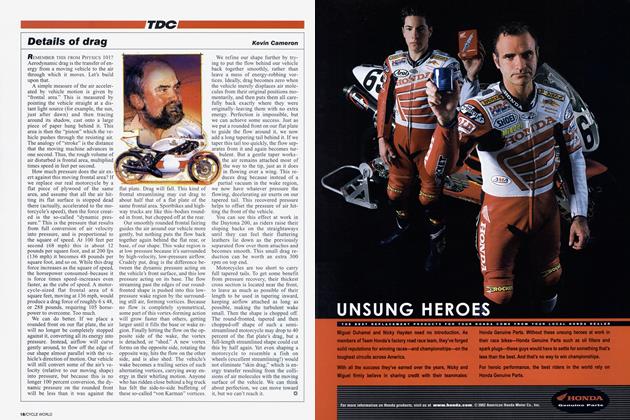

TDC

TDCDetails of Drag

July 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

July 2002 -

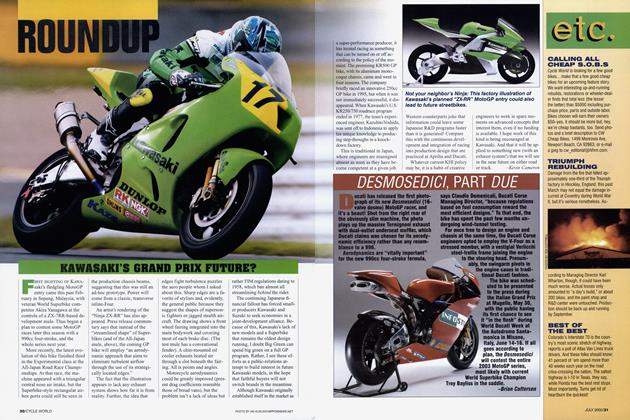

Roundup

RoundupKawasaki's Grand Prix Future?

July 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

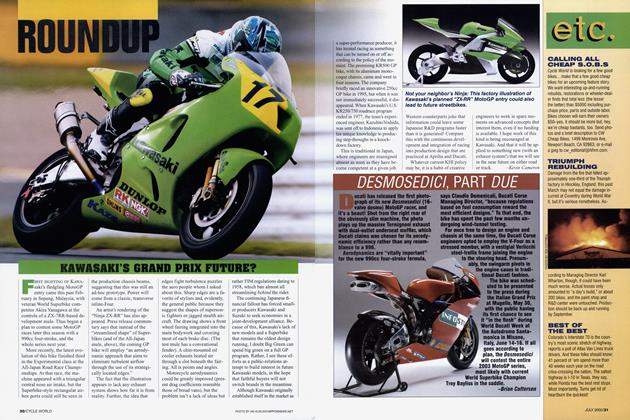

Roundup

RoundupDesmosedigi, Part Due

July 2002 By Brian Catterson