ONE MORE GREAT ADVENTURE

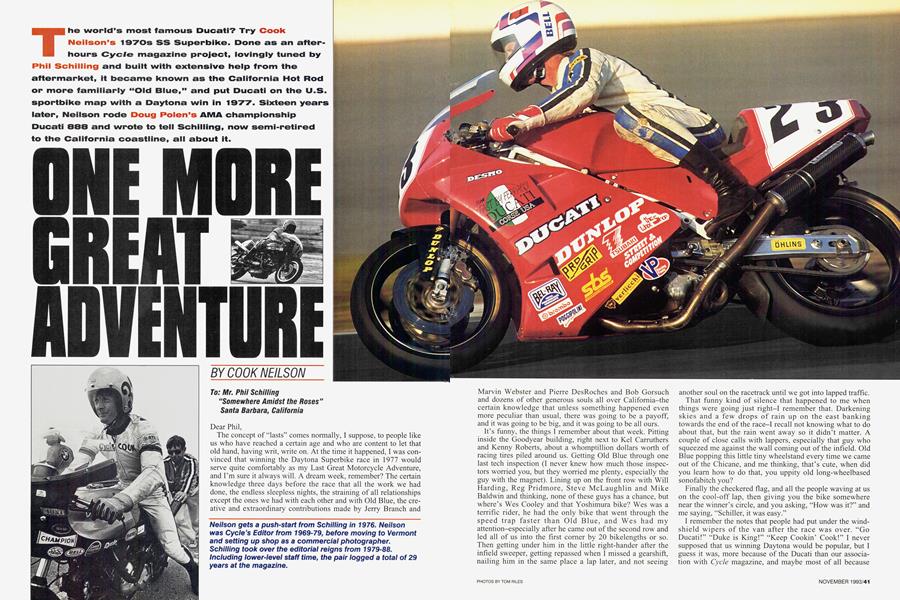

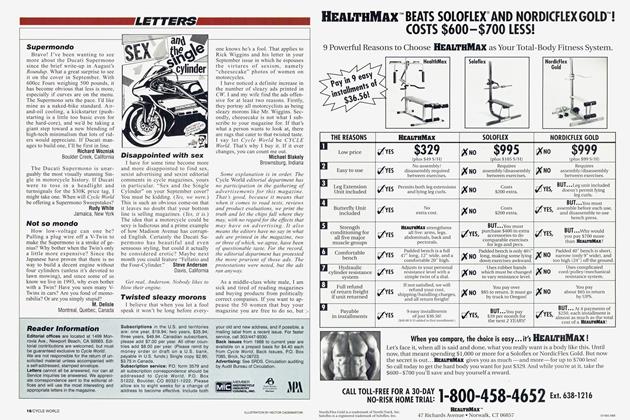

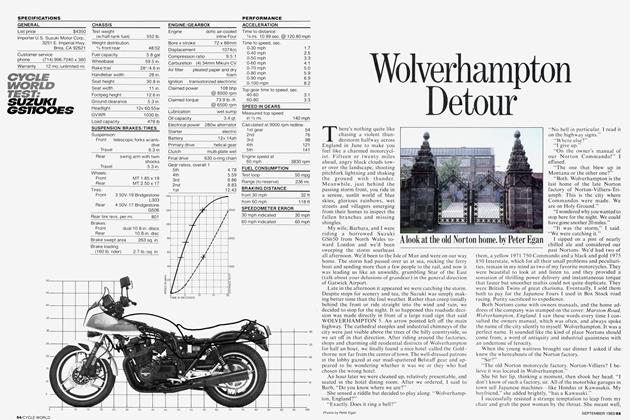

The world’s most famous Ducati? Try Cook Neilson’s 1970s SS Superbike. Done as an after-hours Cycle magazine project, lovingly tuned by Phil Schilling and built with extensive help from the aftermarket, it became known as the California Hot Rod or more familiarly “Old Blue,” and put Ducati on the U.S. sportbike map with a Daytona win in 1977. Sixteen years later, Neilson rode Doug Polen’s AMA championship Ducati 888 and wrote to tell Schilling, now semi-retired to the California coastline, all about it.

COOK NEILSON

To: Mr. Phil Schilling “Somewhere Amidst the Roses” Santa Barbara, California

Dear Phil,

The concept of “lasts” comes normally, I suppose, to people like us who have reached a certain age and who are content to let that old hand, having writ, write on. At the time it happened, I was convinced that winning the Daytona Superbike race in 1977 would serve quite comfortably as my Last Great Motorcycle Adventure, and I’m sure it always will. A dream week, remember? The certain knowledge three days before the race that all the work we had done, the endless sleepless nights, the straining of all relationships except the ones we had with each other and with Old Blue, the creative and extraordinary contributions made by Jerry Branch and Marvin Webster and Pierre DesRoches and Bob Gorsuch and dozens of other generous souls all over Califomia-the certain knowledge that unless something happened even more peculiar than usual, there was going to be a payoff, and it was going to be big, and it was going to be all ours.

It’s funny, the things I remember about that week. Pitting inside the Goodyear building, right next to Kel Carruthers and Kenny Roberts, about a whomptillion dollars worth of racing tires piled around us. Getting Old Blue through one last tech inspection (I never knew how much those inspectors worried you, but they worried me plenty, especially the guy with the magnet). Lining up on the front row with Will Harding, Reg Pridmore, Steve McLaughlin and Mike Baldwin and thinking, none of these guys has a chance, but where’s Wes Cooley and that Yoshimura bike? Wes was a terrific rider, he had the only bike that went through the speed trap faster than Old Blue, and Wes had my attention-especially after he came out of the second row and led all of us into the first comer by 20 bikelengths or so. Then getting under him in the little right-hander after the infield sweeper, getting repassed when I missed a gearshift, nailing him in the same place a lap later, and not seeing

another soul on the racetrack until we got into lapped traffic.

That funny kind of silence that happened to me when things were going just right-I remember that. Darkening skies and a few drops of rain up on the east banking towards the end of the race-I recall not knowing what to do about that, but the rain went away so it didn’t matter. A couple of close calls with lappers, especially that guy who squeezed me against the wall coming out of the infield. Old Blue popping this little tiny wheelstand every time we came out of the Chicane, and me thinking, that’s cute, when did you leam how to do that, you uppity old long-wheelbased sonofabitch you?

Finally the checkered flag, and all the people waving at us on the cool-off lap, then giving you the bike somewhere near the winner’s circle, and you asking, “How was it?” and me saying, “Schiller, it was easy.”

I remember the notes that people had put under the windshield wipers of the van after the race was over. “Go Ducati!” “Duke is King!” “Keep Cookin’ Cook!” I never supposed that us winning Daytona would be popular, but I guess it was, more because of the Ducati than our association with Cycle magazine, and maybe most of all because the bike was not, in the deathless words of Ducati owners-club director Joel Eliel, one of “them wobbling garbage-can Jap four-cylinders,” but rather a Euro-American Twin that was small, sounded like a Harley and went like jet-stink.

So Daytona that year was the top of the mountain for me, my Last Great Motorcycle Adventure. It was more than just a Superbike race, more than just a few moments of that transcendental, perfect silence. Daytona meant to me that when the time came, I could just let go of racing, let go of the way racing breaks into where you live at inappropriate times and knocks the furniture around. Winning Daytona meant that for the rest of my life I could remember without regret the thousands and thousands of hours you and I poured into motorcycle racing and could feel, more than anything else, calm.

There have been other Motorcycle Adventures since. Not Great Motorcycle Adventures, surely, but Adventures all the same. Going with Freud Freudenberger and Kenny Roberts to Hawaii and riding up and down this succulent road Freud knows on Molokai, then watching KR launch that borrowed, brand-new RZ350 as far out in the Pacific as it would go, trying, I reckon, to ride it all the way to Japan. Being with Kenny in Germany when he won his first world championship. Traveling with Malcolm Forbes through China. But all that was back in the late Seventies and early Eighties, and to tell you the truth, Eve got other hankies in the laundry besides motorcycling, and I can go for days and days without thinking about it.

Then one day last summer I happened to be watching television when I surfed into some coverage of Laguna Seca, and there was Doug Polen going at it with Scott Russell. Polen was on an Eraldo Ferracci Ducati, Scott on one of Rob Muzzy’s Kawasakis. Russell was in front until Doug nailed him coming out of one of Laguna’s medium-fast infield comers, and held him off apparently easily for the win. Whoa, I remember thinking, something’s going on here. This ain’t your average Ducati, and chances are that Scott’s ride was your average Muzzy Kawasaki, which is to say, fast, and capable. Then they interviewed Scott, and he said basically that he knew Polen and the Ducati were back there, and that he felt it was just a matter of time before Polen whacked him. Whoa! So Scott was expecting this? This was...normal? At Laguna, of all places?

I don’t know about you, Phil, but I always figured there

were good Ducati tracks and bad Ducati tracks. Much as I loved Laguna, I always figured it was a bad Ducati track, mainly because of (what was then) Tum Nine. Nine-now Turn 11 —is a dead-slow left-hander that empties onto Laguna’s uphill straight. The four-cylinders always used to kill us there, because Old Blue’s low-gear acceleration wasn’t the greatest. And here was Polen, not giving away a thing to Muzzy’s Kawasaki, and maybe even picking up a bit, coming out of that very same comer!

Russell would go on to win the AMA Superbike Championship last year-Polen meanwhile was concentrating on winning his second straight World Superbike Championship—but I figured Doug and his bike might show up at Loudon ’92, so I went over there to watch, and maybe mn into Eraldo, whom I had known back in 1967 when we were both involved in drag racing on the East Coast. Ferracci and Polen were in Europe that weekend, dam the luck, but there was another one of Eraldo’s bikes at Loudon, ridden by a very good Canadian named Pascal Picotte.

You probably haven’t been to Loudon in a while, Phil, but they changed it from a disgraceful old bull ring with a short, irritating road course into an ultra-modem, aluminum grandstanded super-facility with a short, irritating road course. I happened to be sitting in those aluminum grandstands when Picotte came past during an early-morning practice session, and I swear to God, Phil, those aluminum planks started to hum, and as Picotte accelerated out onto the front straight, this resonance would follow him all the way down to Turn One. Four-cylinders going by? Nothing. Yamaha 250s and 600 supersports? Nothing. Here comes Pascal and all that aluminum starts to dance and shimmer, and Em thinking, not your average Ducati....

Scott Russell won that weekend, but I had a chance to at least experience something of what these modern Superbike Ducatis were all about. Don’t get me wrong. Even though I live in Vermont, we do have mail delivery here and electricity, so occasionally there arrives a motorcycle magazine or two, and we do have television. So for the rest of ’92 and early ’93, I watched and studied and wondered, what manner of Ducatis are these?

Came the phone call in June. It was David Edwards, Cycle World’s Editor. If he could arrange it, he asked, how would I feel about taking a spin on Polen’s Ducati at Loudon, and compare it to Old Blue? Of course I said yes, even knowing

the risks. I had no other choice.

The risks were not inconsequential. I have not been on a high-performance motorcycle since Riverside 1977, 16 years ago. I had never ridden at Loudon, but having seen a lot of races there, I was not predisposed to like it. Finally, not to put too fine a point on it, there was a good chance I would make a dork out of myself. I go to Loudon, crawl on Polen’s Ducati, look inevitably aging and inept. The near-siders murmur, “We knew it all along; you couldn’t have been that great.”

But however easy it would have been to say to David, no, thanks, it’s been too long, I’ll just stay here in Vermont and remember how neat things used to be and not risk discovering new inadequacies; instead of doing that, I said yes.

The bait was irresistible, as I’m sure you know. A chance another magic motorcycle-another Ducati. As my wife (the High Stepper, she said she wouldn’t miss this for the world) and I were driving over to Loudon, I kept going back again and again to the races I had seen on TV. There’s Polen, at the beginning, mired deep in the pack. There’s his tachometer, the needle bouncing up around 12,000 accompanied by a fine, sturdy drone. And now Polen’s on the move, picking off the frontrunners. Here's Polen centerpunching a big haybale kicked onto the Charlotte Speedway high banks by Miguel DuHamel's crash ing Kawasaki. Here's Polen stalking Mike Smith at Road Atlanta, here he is bedeviling

in a lifetime to ride a bike that is not only in a class by itself, but also to see if it bears any resemblance to another bike which was in a class by itself-Old Blue. If 16 years of reflection about our racing effort has yielded anything, Phil, it is this: The certain knowledge that our Ducati Superbike was vastly superior to anything it had to race against. I know this because I know what my own skills were, and even though you and I never discussed it, you certainly must have known, too-I really wasn’t such a hot pilot. Which is of course the reason we spent so much time and effort and money on the bike. I rode other bikes back then, remember. I rode two or three times for BMW. I rode the Racecrafters Kawasaki. I rode Jess Thomas’s Yamaha TZ350. Every time it was a struggle, and every time I came back to the Ducati thinking, I’m really lucky to have this bike. Whatever it may have lacked in tenus of lower-gear acceleration, it more than compensated with its honorable disposition, its usability, its balance and its completeness. I can’t remember how many times I gave the bike to you after one practice session or another and said, “Well, Phil, it’s all there.” Old Blue was very much a magic motorcycle. Since no one else ever raced it during the time we were campaigning it seriously, no one but you and I ever knew how magic it really was, and I’ll tell you, Phil, sometimes I

would almost feel sorry for some of the other guys.

But at the same time, I knew deep in my bones that if one of the really good Superbike guys-DuHamel and David Aldana early on, Hurley Wilvert, Wes Cooley, Mike Baldwin, David Emde, Reggie Pridmore most of all-got their hands on a bike that had anywhere near the style that Old Blue had, the rest of the field would be dead meat.

So now it’s 16 years later, and I’ve got a date with

DuHamel and Russell at Laguna Seca, here he is at Phoenix, and Elkhart Lake. And here he is, winning at almost all of these places. Sometimes, clearly, he has to ride hard at the end to win, occasionally he even loses-Daytona, Loudon, Mid-Ohio-but by and large he wins, and wins with more in reserve, it appears, than he would have us suspect. It was often said of Willie Mays that his special flair, contrary to baseball orthodoxy, was making the easy ones look hard. Might Doug Polen and Eraldo Ferracci and their booming Ducati, I wondered, likewise have that same special flair?

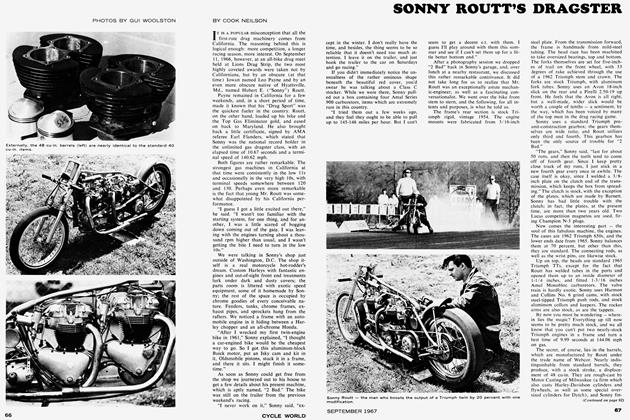

The first thing I noticed driving onto the Loudon grounds wasn't the rather splendid racing arcade that has been con structed. It was the transporters. We all used to go racing in Econolines and Beauvilles. Now Kawasaki and Honda and Suzuki and Yamaha use monstrous moving vans to get around the country, and they're filled not only with motor cycle racing equipment and spares, they've got machine shops in there. I hope Eraldo doesn't have one of those things, I remember thinking. Sure enough, he doesn't. When I first saw him that sunny Wednesday, he and one of his assistants had just finished unloading "my" bike from his lit tle red cube truck. So far so good, I thought: underdog trans porter, overdog motorcycle.

It was good to see Eraldo again, Phil. I don't know if you ever knew him, but I first ran into him back in the late Sixties, at Cosmopolitan Motors, about two weeks after he had come here from Italy. He had been an R&D engineer for Benelli, and had been sent here to see what could be done to freshen up the company's leftover motorcycles. His plan called for a new paint job, more engine displacement, a five-speed gearbox and a little assembly line in Germantown, Pennsylvania.

A year later, the job was done, and Ferracci was ready to return to Italy. But by then, the Benelli Brothers, not espe cially thrilled, with the way the motorcycle industry was going and starting to think of retirement, suggested that while Eraldo was certainly welcome to come home, perhaps he might find better opportunities in America than in Italy. So he stayed, went to work for a Honda dealer, and lasted there for 15 years. By 1986, he had his own place, and while still servicing his drag-racing clientele, he also had about 10 roadracing customers. One of these was Dale Quarterley, who had a Ducati, and who won a lot of races.

"In 1987," Eraldo told me, "I contacted the Ducati facto ry, and they gave me a bike-not really to develop or make changes on, but simply to race. We won six or seven races that year, and then the next year I had Jamie James and one of the Raymond Roche factory bikes. But my rela tionship with Ducati goes back a lot farther than that. I used to race Ducatis myself, and won a championship for them in 1958. So when I got back in touch with the facto ry, I knew everybody."

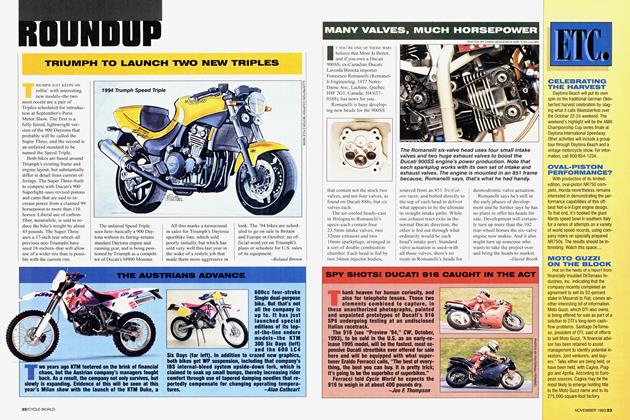

Thus was Eraldo anointed, and as he stands in the Loudon pits ready to hand me one of his Ducatis, he has won more Battle of the Twins races than he can remember, two World Superbike Championships and most of the 1993 AMA Superbike Championship (which he and Polen would wrap up at Mid-Ohio in mid-August). All of this he has done with-and for-Ducati, and let me tell you, Phil, that between Ferracci and Ducati and the Castiglioni family and Weber and some American suppliers that Eraldo calls upon, there has evolved an extremely serious racing motorcycle. In the form that I rode it, this 888cc Twin weighs about 320 pounds and makes 142 horsepower. In every sense the bike is a delicacy. Remember that fly that was molded into the fiberglass fuel tank of our bike? The one that you said was surely the most famous fly ever exported from Italy? There are no such flies on Eraldo’s bike. Instead there is much carbon fiber, supplied by the same company that provides it for Ferrarri’s Formula One effort. There is much flawless red paint, meticulously crafted cooling apparatus and militarygreen magnesium. It is heart-breakingly lovely.

Before Eraldo and his helper fire up #23, there are some ancillary matters to attend to. Sensing that I might be uncomfortable with the fancy new carbon brakes, Eraldo has them replaced with more conventional ones, and then there is the business with the computer. It is about the size of a VHS tape, and there are wires coming out of it as thick as

your little finger. Eraldo plugs this module into his laptop and starts talking to it. I have no idea what they are saying to each other, but I can imagine:

Computer: Name Rider Rolen Picotte/// Ferracci: Other///

Computer: Name Other///

Ferracci: Neilson///

Computer: Nothing Found Describe///

Ferracci: Aging Former «Journalist, Raced Ducati Late '70s///

Computer: How Aging///

Ferracci: Little Under 50///

Computer: I Know The Guy///

“The computer is made by Weber-the same company that makes the fuel injection-and it controls everything, but within a pretty narrow range,” Ferracci said. “It reads all the temperatures, air density, air pressure inside the airbox, everything, and then adjusts the fuel mixture and the spark timing, and it does it every crank revolution. But we don’t let it do too much. If we’re going from Daytona, for example, to here, where the elevation and air density and temperature are much different, we just put in a different chip, or E-PROM.”

Well, Schiller, that’s progress. We had Kmart ignition coils and a welded-up centrifugal-advance mechanism; Eraldo has a black box. We had 40mm Dell’Orto carburetors with the accelerator pumps backed off; Eraldo has a pair of 50mm fuel-injector bodies. We had two valves per cylinder and a compression ratio of about 10:1; Eraldo has four-valve heads and 11.8:1. We had a stock, albeit carefully assembled, fork and extra-length S&W shocks; Eraldo’s Ducati comes with an upside-down fork and a rear monoshock, both made by Öhlins. We had desmo valve gear; so does Ferracci, but his is driven by those awful toothed-rubber belts instead of decent, God-fearing towershafts and bevel gears, so score one for the good guys.

There’s something else Eraldo has, and that’s a microswitch down on the shift lever. It communicates with the computer, Ferracci was explaining. When you want to shift up, forget the clutch lever, forget the throttle, just boot it. Try it, he said, you’ll like it.

While I was digging my way into my old leathers and trying on the new helmet that Bell had sent along for this exercise, Eraldo and Hoak the helper were warming up the bike. I was amazed at how quiet it was, Phil. Of course, it does wear mufflers, unlike Old Blue, which just had some long Conti shells with reverse cones welded on. Still, beneath the quiet there is real authority to the way Eraldo’s bike sounds, even just sitting on its stand and getting ready for the day. A minor glitch is attended to and Eraldo shuts down the engine and wheels it out to the pit wall.

I hop on, Eraldo and Hoak give me a push, the engine starts right up, and I’m telling you, Phil, if this isn’t the American Dream I don’t know what is; a gorgeous day, track all to myself, a rare and precious motorcycle to get to know. My personal parameters were in place; be comfortable with being slow was the primary one, and the second, closely related, was don’t crash trying to impress myself or anyone else.

The Loudon track is a web of trickery. After the front straight there is a decreasing-radius left, a tight little right and a medium left leading onto the track's only infield straight. Then it goes uphill off-camber to the right, over the crest of a hill and down into a bowl-shaped left, the proper line for which includes the following uphill left. After that it leans right, then there’s a weird downhill left, and a hard right with a pavement change thrown in. The last part includes a sweepy left, then a really aggravating left-rightleft that leads you out onto the top of the front straight.

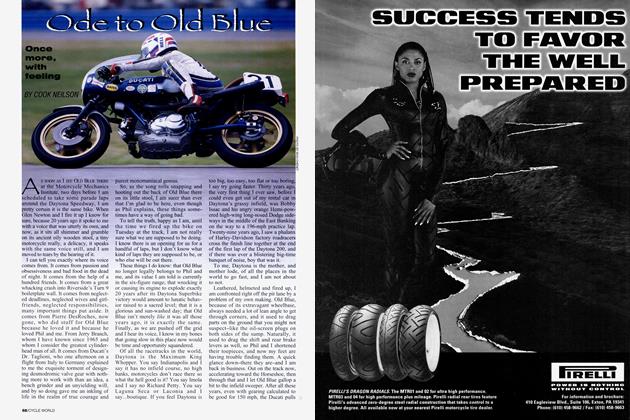

I must say, Phil, that I found it all rather daunting, certainly for the first couple of laps. But by the same token I was having the time of my life, because I was beginning to suspect that Eraldo’s Ducati does all the same lovable things that Old Blue used to do, the biggest difference being the volatility and precision with which it does those things. Our bike was extremely steady, especially in comparison to the bikes it was racing against; this one feels Mt. Everestine. Our bike delivered a smooth flow of very adjustable horsepower all the way up to around 9000 rpm; the Polen bike does the same, only 60 percent more, and probably up to 13,000 rpm. With its plasma-coated aluminum brake rotors and a mixture of magnesium Fontana and Lockheed calipers, Old Blue stopped beautifully; Eraldo’s Ducati stops like you’ve run it into the back of a bus. Our Ducati, at around 380 pounds, was a real lightweight for its time; Ferracci’s, at 320, is likewise, and this advantage, as any racer knows, is truly a gift that keeps on giving. Old Blue’s special magic was that I could ride it, plain and simple; Em sure that Polen must feel the same way about his bike.

But of all the obvious leaps of progress that have been made in the Ducati neighborhood over the past 16 years, the one that stands out the most vividly is sheer power. Towards the end of my first session with Eraldo’s bike, I went ahead

and let it rip down the front straight, and I swear, Phil, the power this thing makes is a major miracle. Turn on the gas and power comes out it like a waterfall, and it doesn’t feel peaky, either. Anything over about 5000 rpm, watch out. I remembered asking Eraldo where to shift. He said, “Shift it wherever you want; you’re not going to hurt it.” So I flashed back to all that TV race coverage that came from Polen’s onboard lipstick camera and figured if 12,000 was good enough for Doug, it’s good enough for me. But the bike has such a close-ratio gearbox, and was fitted with such a tight final-drive ratio, that it was hard to keep up with; it was even hard to know when I was out of gears to shift.

By now I had been on the track for five or six laps, and I needed some time to get my bearings; this bike does rush you around, after all, and I must admit that my circuits were lighting up red all over the place. Besides, Eraldo’s little miscroswitch on the shift lever was misbehaving.

“Well, what do you think?” Ferracci asked after I had given him back the bike. “Have a nice time?”

To be honest, I didn’t know what to say. That this was by a margin only calculable in light-years the best motorcycle I had ever been on was obvious, so I said that, and Eraldo set to work on his little microswitch. But there was a lot I didn’t say, Phil, at least not then. I didn’t say how privileged I felt to be in the same state as this Ducati, much less on it. I didn’t say how proud I was of Ducati, and Eraldo, and Polen for doing unimaginably well what you and I set out to in 1976. I didn’t say how pleased I was to sense that the solution you and I came up with back at the dawn of Superbike racing-build a bike a guy can ride, build a bike a guy can trust-is as effective now as it was then.

Don’t let me mislead you into thinking that I was out there on the limit with Polen’s motorcycle, Phil-far from it. Eraldo does have stopwatches, you see, and even knows how to work the knobs. I knew before I left Vermont that I was going to be slow, and that’s exactly how it would turn out.

By now Ferracci had the microswitch doing what it was supposed to do, and he really wanted me to try it, so I said okay. What it is, is a shifter-mounted kill-switch, only better. When you press down on the lever to shift up a gear, the switch sends a signal to the computer, and the computer shuts everything down for three-hundredths of a second. During that power outage, gears are reorganized, and you don’t have to fiddle with the clutch or the twistgrip. The point isn’t just quicker gearchanges; it’s being able to be very still on the bike, which is nice if you have to shift coming out of a corner. It’s the next best thing to an automatic transmission.

My next couple of practice sessions went better. I was still slow, but beginning to feel less uncomfortable, and so was able to notice things other than the bike’s stupefying blast of acceleration. I noticed, for example, how good the tires have gotten. These were Dunlops, great big Dunlops, and I was amazed at how solid they felt. I believe it when the fast guys talk about skidding these things through and out of corners, but it’s beyond me how. Old Blue never did any of that foolishness, and I’m sure Polen’s bike, with me on it, didn’t either.

I was dazzled at the bike’s responsiveness. I think we have to admit, Phil, that Old Blue wasn’t exactly your typical quick-twitch motorcycle. It had just under 60 inches worth of wheelbase and front-end geometry out to there, and if it was a horse to get through the Riverside esses, at least it didn’t wobble and shake. Eraldo’s bike has about 5 inches less wheelbase, 6 degrees less steering-head angle and 55 pounds less weight; believe me when I tell you it goes where you point it, and when.

Now I know engineering in more steering responsiveness is something Ducati’s racing department is working on. Polen was heard to say later that afternoon, “If you’ve got a bike at Loudon that won’t turn, you’re dead,” the obvious hint being that he might be in exactly such a pickle. Well hell, Doug, it’s in the genes. Old Blue used to push the front end through all kinds of comers, the problem being that the front cylinder takes up a lot of space behind the tire, thus biasing weight towards the rear. In any case, this was not a problem I had; to me, Eraldo’s bike felt like it turned quicker than greased lightning.

When I had been at Loudon the year before, I did notice one thing, though: Picotte’s bike seemed to spend an inordinate amount of time with its front wheel in the air. By my second or third go-round on Polen’s bike, I came to understand that this, too, must be in the genes, and not just Ducatis, either, but deep in the double-helixes of all modem Superbikes. You’ve got these short little wheelbases, engines mounted high, lots of horsepower and huge sticky tires, and if these ingredients aren’t enough to get 'em to rear up, I wouldn’t know what to add. This Ferracci Ducati is no different; it wanted to stand up all around the track. Controlling it, for me, was simple: just roll off the gas a smidge. But people like Polen don’t have that luxury, and I can only guess that they deal with the problem through very careful selection of gear ratios and enough wheelspin coming off corners to keep the back end from hooking up hard at inopportune times.

By now I have been out on this wondrous machine of Eraldo’s four or five times, and I hate to admit

it, Phil, but I was getting bushed. Parts of my left hand had been hammered into numbness by the Ducati’s vibration, and both arms and shoulders were good and sore from all that yanking around they were getting. We had one last photo session to do-back and forth through the same corner, just like we had to do with all those streetbikes we tested-and the Ducati behaved, well, just like a streetbike. Then it was back to the pits, pitch the bike in the back of Eraldo’s little red cube truck, and head out for dinner and just a few more questions.

Eraldo on his loyal opposition: “Before, the Japanese didn’t have any Superbike competitors; now, they do. This is good for the Japanese people; otherwise they’d get lazy, like the Italians did in 1960. Unless the Japanese want to quit, they have to go back and do some more work. Five years ago, everybody in the racing departments in Japan didn’t have anything to do; now they’ve got to work. That’s what’s good about competition. The Japanese don’t mind doing a little work, and they’re certainly capable of going faster than the Ducati. They’ve already proven that-they won Daytona, they might win the World Superbike Championship this year.

“And you’ve got to give credit to who’s on the Ducati. Polen is a professional, he’s a calculator, he’s smart. With Doug, we can go to any racetrack in the world and get the bike dialed-in before anybody else. Everybody in Superbike racing thinks Polen’s the best there is. With Doug, we end up changing the bike very little, whether it’s Japan, or here,

or Europe. Some other riders, you’ve got to change the whole bike, then you end up back where you started. But Doug was bom with a sensitivity to motorcycles. Fie makes Ducati, makes me, makes everybody he associates with in racing, look good.”

To anybody who has carefully watched the Superbike class this year, I said, it is apparent that, on most tracks, Polen is toying with the other guys. He doesn’t get great starts. He seems to be able to wander towards the front of the field and get lovely racing footage on the way with his onboard camera and then, right near the end, pop into the lead. Is the point to win, but not by too much?

“You got it. Suppose you improve this and put on that and all of a sudden you go real fast, what happens? They change the rules! So we’ve been working on getting the chassis good and making sure the bike doesn’t break. The first time I went over there (Europe), everybody said slow down, slow down, but I wanted to win. Now I know why: They change the mies.”

Polen is more cagey about this. “Laying back and making

my move at the end-that’s been forced on me by circumstances,” he claims. “I’ve never had a really good clutch; when you do a standing start, the dry clutch on these bikes ends up chattering so hard that it’ll bend the pins in the chain, stretching it. That’s what happened to us at Daytona in ’91,” he says, explaining that the chain was stretched so much it sawed its way into the engine cases.

We reconvened at the track the next day, Phil, and I must say I experienced a bit of reality. Eraldo’s other truck had arrived, along with some sort of luxo-trailer. In the other truck were the Ducatis that had come in from the previous weekend’s racing at Elkhart Lake, and there were lots of them. There were also about a half-dozen complete spare engines. This is much more Big Time than I realized, I remember thinking. This is a major factory effort.

Of course it is, and if it operates differently than what you and I and Old Blue were about, well, there it is, and so much the better. The playing field is different now, Phil; it’s not the backyard anymore. And I must say, from one old Ducatista to

another, it’s great fun to watch. We always thought that Old Blue gave us an unfair advantage, and isn't that, in the words of Roger Penske, what racing is all about? That the Polen Ducati has an unfair advantage is manifestly clear. What tickles me is that it’s exactly the same unfair advantage we had 16 years ago. Eraldo says it best: “It’s a complete package, the Ducati. The engine’s good. You can drive it good. It handles good. The carburetion’s perfect. So even if you’re down six or seven horsepower, you can drive that bike 100 percent almost every time you go out.”

As the High Stepper and I took our leave, I couldn’t help but think: probably the best two Ducatis ever, separated by 16 years but united in their character, in their soul. And only one lucky sonofabitch ever got to ride them both.

Fondly,

View Full Issue

View Full Issue