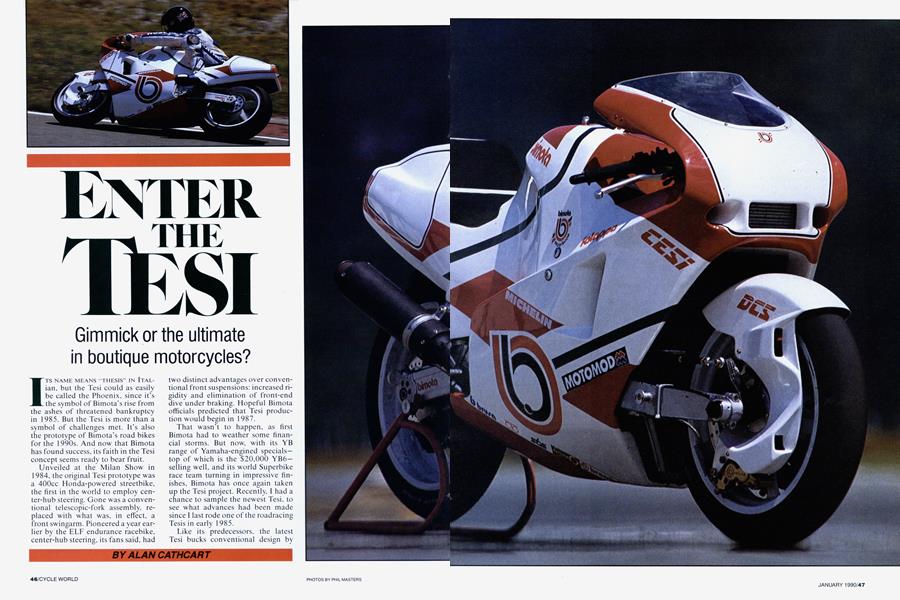

ENTER THE TESI

Gimmick or the ultimate in boutique motorcycles?

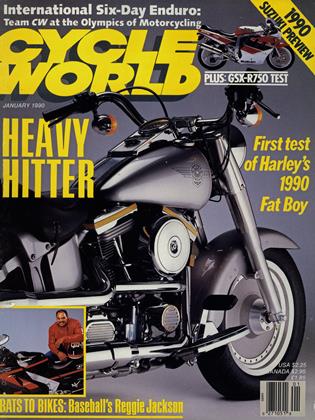

ITS NAME MEANS “THESIS” IN ITALian, but the Tesi could as easily be called the Phoenix, since it’s the symbol of Bimota’s rise from the ashes of threatened bankruptcy in 1985. But the Tesi is more than a symbol of challenges met. It’s also the prototype of Bimota’s road bikes for the 1990s. And now that Bimota has found success, its faith in the Tesi concept seems ready to bear fruit.

Unveiled at the Milan Show in 1984, the original Tesi prototype was a 400cc Honda-powered streetbike, the first in the world to employ center-hub steering. Gone was a conventional telescopic-fork assembly, replaced with what was, in effect, a front swingarm. Pioneered a year earlier by the ELF endurance racebike, center-hub steering, its fans said, had two distinct advantages over conventional front suspensions: increased rigidity and elimination of front-end dive under braking. Hopeful Bimota officials predicted that Tesi production would begin in 1987.

That wasn’t to happen, as first Bimota had to weather some financial storms. But now, with its YB range of Yamaha-engined specials— top of which is the $20,000 YB6— selling well, and its world Superbike race team turning in impressive finishes, Bimota has once again taken up the Tesi project. Recently, I had a chance to sample the newest Tesi, to see what advances had been made since I last rode one of the roadracing Tesis in early 1985.

Like its predecessors, the latest Tesi bucks conventional design by using center-hub steering and by using its engine as a fully-stressed chassis component. The new prototype’s Yamaha FZR750 engine seems ideal for this purpose, thanks to its forward-inclined cylinders, the cam covers of which provide mounting points for a chrome-moly-steel subframe that holds the steering head. That same subframe also provides the upper mount for the rear Marzocchi shock and it supports the one-piece seat/tank unit.

ALAN CATHCART

Another problem lies with the differentially geared steering, which though it works just fine at low speeds, becomes progressively more disconcerting the faster you go. The strange thing is that it doesn’t actually misbehave. You only think it does. So when you’re about halfway around a fast turn it seems the bike is understeering dramatically—you’ve applied more pressure to the bars than you'd have expected to be necessary, without the appropriate degree of response from the front wheel and chassis. However, all is well. Your response actually is lagging behind the bike’s actions. “Hey, is this bike really going where I want it to go?” you ask yourself. Yes it is. You’re just not sure it is, at least not until you log some time on the bike and get accustomed to its handling. Unfortunately, the mechanical system takes up more space than the old hydraulics, requiring that the twin four-piston brake calipers for the 320mm Brembo discs be mounted opposite the steering-link pivot at the bottom of the discs. Track testing has shown that overheating is now a problem with the Tesi’s brakes, presumably because of the shrouded location of the rotors. Bimota Chief Engineer Pierluigi Marconi intends to widen the front swingarm to give more steering lock for street use, and when he does that, he’ll relocate the discs further apart to get more cooling air to them.

CON

Two pairs of alloy engine plates are bolted to the front and rear of the engine to provide pivots for the swingarms at either end of the bike. The rear swingarm is a modified Bimota YB4 unit, but the front one is fabricated from sheet steel and gives about 23 degrees of steering lock; more than adequate for track use, and acceptably close to the 30 degrees needed for the street. This front swingarm feeds suspension loads into another single shock mounted vertically in front of the engine.

The bike is steered through a fairly normal-looking pair of triple clamps into which are slotted a pair of meaty tubes that not only provide a location for the conventional clip-ons, but also for the steering damper. The triple-clamps pivot on the front of the subframe and operate an abbreviated steering column, offset to the left via a short drag link, which is geared to provide a variable steering ratio. A small degree of movement of the bars from the straight-ahead position results in an even smaller amount of lock on the front wheel, but as the bars are turned farther, the ratio picks up until at around 10 degrees of lock, it’s 1:1.

The lower end of the steering column pivots in a plate bolted to the engine and operates another drag link, which runs forward along the left of the wheel and rotates it via a kingpin and twin conical bearings mounted in the center of the wheel. This mechanical steering is a big difference from the original Tesi. which had hydraulically activated steering that constantly gave problems.

Brake overheating notwithstanding, my first impressions of the bike, gathered during a test session at Yugoslavia’s Rejika GP circuit, are of complete normality, though at low speeds, the Tesi’s steering is a bit heavier than on a conventional motorcycle, almost as if the steering damper is too tight. At faster speeds, the Tesi is not only stable but gives a remarkable degree of road feel, the lack of which has been a major complaint on center-hub bikes.

Not only could I feel the front suspension compressing and rebounding as I entered and exited Rijeka's several dips and dives, I could also feel the change in track surface transmitted by the front tire. Later, as I grew more comfortable with the Tesi and worked up to speed. I could feel the front suspension complain as it objected to having cornering and braking forces fed too violently into it at the same time.

This degree of sensitivity in a center-hub design is evidence of a real breakthrough in terms of transmitting road information to the rider, but the Tesi wasn't perfect. The front suspension felt too soft on rebound damping, so when it was really thrown into a turn, it pogoed slightly. My response would have been to stiffen the rebound, but Bimota test rider Giancarlo Falappa felt the pogo motion actually derived from a problem with the rear suspension, which was upsetting the front end.

The Tesi retains the great advantage of center-hub bikes in that it allows hard braking even when the chassis is cranked over deep into a turn. In fact, unusual with this type of bike, there’s a certain amount of front-end dive under braking, a characteristic Marconi has dialed in to remove the remote, dead feel delivered by most hub-center machines, as they brake in a perfectly flat plane. There’s not as much dive as on a teleforked machine, but enough not only to convince you that the brakes are actual working, but also to retain that vital road feel which enables you to tell when the front tire is being pushed to its limits.

A Tesi road bike may be very close to reality. Already, Marconi has started work on the prototype road bike which, like all previous Bimotas, will first be tested on the track in competition before it reaches production, most probably for the 1991 model year. This road-going Tesi will be powered by an eight-valve Ducati engine, thanks to a recent agreement between Bimota and Cagiva, Ducati’s parent company. Says Marconi of the Italian V-Twin, “It’s the right engine, no question!”

Whether a production .version of this ultimate in boutique motorcycles will be the right bike for the 1990s remains to be seen. But if a street version of the Tesi can be made to perform as brilliantly as this prototype, I wouldn’t bet against it. El

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSocial Security

January 1990 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeOnce And Future Harleys

January 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsHigh Finance

January 1990 By Peter Egan -

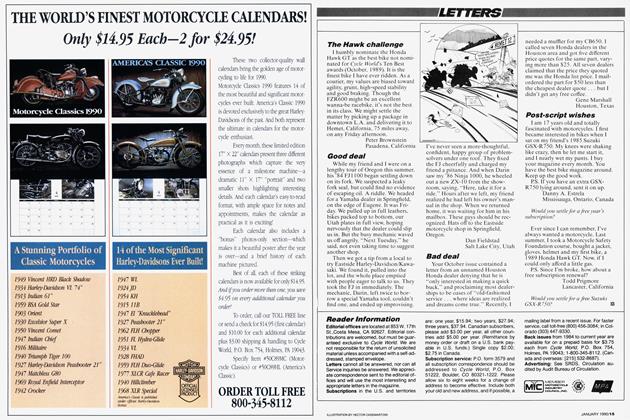

Letters

LettersLetters

January 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupSwiss Citybike: Motorcycles Become Electric

January 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupStarts of the Tokyo Motor Show

January 1990 By David Edwards