AMERICAN FLYER

RACE WATCH

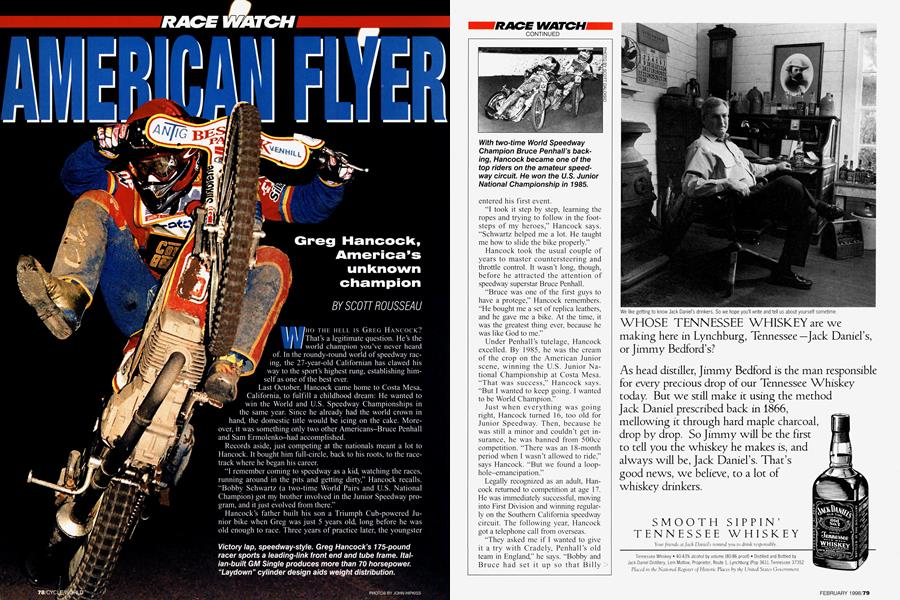

Greg Hancock, America's unknown champion

SCOTT ROUSSEAU

WHO THE HELL IS GREG HANCOCK? That’s a legitimate question. He’s the world champion you’ve never heard of. In the roundy-round world of speedway racmg , the 27-year-old Californian has clawed his way to the sport’s highest rung, establishing himself as one of the best ever.

Last October, Hancock came home to Costa Mesa, California, to fulfill a childhood dream: He wanted to win the World and U.S. Speedway Championships in the same year. Since he already had the world crown in hand, the domestic title would be icing on the cake. Moreover, it was something only two other Americans-Bruce Penhall and Sam Ermolenko-had accomplished.

Records aside, just competing at the nationals meant a lot to Hancock. It bought him full-circle, back to his roots, to the racetrack where he began his career.

“I remember coming to speedway as a kid, watching the races, running around in the pits and getting dirty,” Hancock recalls. “Bobby Schwartz (a two-time World Pairs and U.S. National Champion) got my brother involved in the Junior Speedway program, and it just evolved from there.”

Hancock’s father built his son a Triumph Cub-powered Junior bike when Greg was just 5 years old, long before he was old enough to race. Three years of practice later, the youngster entered his first event.

“I took it step by step, learning the ropes and trying to follow in the footsteps of my heroes,” Hancock says. “Schwartz helped me a lot. He taught me how to slide the bike properly.” Hancock took the usual couple of years to master countersteering and throttle control. It wasn’t long, though, before he attracted the attention of speedway superstar Bruce Penhall.

“Bruce was one of the first guys to have a protege,” Hancock remembers. “He bought me a set of replica leathers, and he gave me a bike. At the time, it was the greatest thing ever, because he was like God to me.”

Under Penhall’s tutelage, Hancock excelled. By 1985, he was the cream of the crop on the American Junior scene, winning the U.S. Junior National Championship at Costa Mesa. “That was success,” Hancock says. “But I wanted to keep going. I wanted to be World Champion.”

Just when everything was going right, Hancock turned 16, too old for Junior Speedway. Then, because he was still a minor and couldn’t get insurance, he was banned from 500cc competition. “There was an 18-month period when I wasn’t allowed to ride,” says Hancock. “But we found a loophole-emancipation.”

Legally recognized as an adult, Hancock returned to competition at age 17. He was immediately successful, moving into First Division and winning regularly on the Southern California speedway circuit. The following year, Hancock got a telephone call from overseas.

“They asked me if I wanted to give it a try with Cradely, Penhall’s old team in England,” he says. “Bobby and Bruce had set it up so that Billy could go over there on a trial basis. We did some exhibitions on (World Champion) Erik Gundersen’s bikes, it was a first-class deal all the way.”

Hancock went on to sign with the Cradely Heath Heathens for the ’89 season. It was a difficult transition, though, especially when Hancock’s work permit was nearly revoked after he failed to carry the benchmark average of 6 points per race meeting.

“It was like going back to Third Division all over again,” he says. “I was developing as a top-class rider in Southern California, but when I got to England, it was like going back to school.”

Hancock got off to an excellent start in his second season, and was ranked among the top points-scorers in the British League. He returned to California to contest the American Final-the first step toward winning the World Championship. He rode well, eventually finishing in a three-way tie for first, which guaranteed him a spot in the Intercontinental Final. Then, disaster struck. “I fell off on the second lap and broke my arm,” he remembers.

Hancock was out for four months. When he did return, he was ineffective. “I took the winter off, and I tried to get everything back in order, but I was scared,” he says. “I didn’t want that to happen again.”

Hancock suffered another blow when he was passed over by the AMA in seeding for the ’91 American Final. That put his championship dreams on hold again, and all but crushed his self-confidence. “Those things make you question yourself,” Hancock says. “People didn’t see that I was working my butt off, trying to make the most of my racing career. Things kept dragging me down.”

In ’92, Hancock decided to make things happen. “I bought a house in England, and 1 started racing in the Polish and Swedish Leagues as well as the British League,” he says. “It was a full commitment. I went into debt to buy four brand-new bikes.” Buoyed by his newfound commitment, Hancock started winning, eventually becoming one of America’s marquee riders. He qualified for his first World Final in ’93, the same year Sam Ermolenko became the first American to win the World Championship since Penhall did so in 1981-82. Hancock was back again the following year, just missing a podium finish.

In ’95, the FIM replaced the oneday, winner-take-all World Final with a six-round grand prix format, similar to that used in motocross and roadracing. Hancock remained near the top, finishing fourth again and winning the series finale British GP. He accomplished another goal that year when he won the U.S. National Championship.

Another breakthrough came when Hancock and Hamill landed sponsorship from Exide Batteries. As Team Exide, the Americans provided a solid 1-2 punch, with Hamill taking the title and Hancock finishing third. Seeing his long-time friend lift the World Championship trophy made Hancock all the more determined. “I looked at him and thought, ‘That’s me. I’m going to do that.’”

Hancock resolved that ’97 would be his year. Right out of the gate, he was the man to beat. He defeated Hamill at the series-opening Czech GP, and finished second at the following round in Sweden. At the third round in Germany, Hancock was third.

Just as his points lead began to grow, Hancock’s transporter caught fire on race day at the British GP. The van and two motorcycles were destroyed. Still, Hancock managed seventh on one of his backup bikes, barely keeping the championship lead. If anything, the mishap strengthened Hancock’s will to win. “I had come that far,” he says. “I wasn’t going to let anything get in my way.”

At the Polish GP, Hancock stormed to wins in four of five qualifiers, and topped Hamill in the final. To put a lock on the championship, Hancock needed only to make the “A” Final at the series finale in Vojens, Denmark. He did just that, finishing third in the race. “I was overwhelmed,” Hancock says of winning the title. “I’d enjoyed success before, but this was better than I ever had imagined.”

Yet there he was, back in Costa Mesa, trying to win in front of his hometown fans on a warm October evening. Unfortunately, it didn’t turn out as planned, as Hancock dropped points in the qualifying races and was forced to come through the “B” Final to take his place in the championship race. In the end, he came up just short, finishing second. The win went to “Flyin”’ Mike Faria, who set a record of his own, becoming only the second rider in U.S. history to win the U.S. title more than twice.

“That night, Mike was the man,” says Hancock. “I gave it my best shot. I didn’t win, but I had a really successful year. I have a lot to look forward to next year, and I’m determined to keep pressing on.”

Scott Rousseau, a former Cycle World intern, is an associate editor for Cycle News, covering dirt-track and speedway racing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue