Clipboard

GPs enter a new era

Stagnation is over, let the technical adventure begin. That's the message for the forthcoming grand prix season. After five years of factory V-Fours winning all the races, several alternatives are bidding to break the deadlock.

The most exciting is Kenny Roberts’ new three-cylinder machine, built like a Formula One car in the heart of England’s specialist race-engineering belt. And, of course, there are the V-Twins from Aprilia and Elonda. Meanwhile, three-time 500cc World Champion Mick Doohan is threatening his own switch: The man who showcased Honda’s “Big Bang” NSR500 in 1992 is testing an updated version of the old-style, “Wildcat” engine, which features an evenly spaced firing order.

Doohan remains the man to beat. Dominant since ’94, the Australian no longer complains that racing is boring. Last year, Repsol Honda teammate Alex Criville offered a serious challenge, beating Doohan twice in straight fights. In fact, Criville’s performance set Doohan thinking.

The result is a renewed desire to develop the old engine. Prone to vicious wheelspin and responsible for many high-sides, pre-Big Bang bikes were a handful. But Doohan 'feels a skilled rider can use the wheel-spinning performance to his advantage. “The power delivery of the new engine is a little more fierce,” he said, “and with the way I ride, it allows me to open the throttle earlier accelerating out of a corner.”

Doohan first tested the new engine after last-year’s Australian GP, shaving more than a second off his previous best lap time. Criville tried the bike, too, but fell. At the latest round of tests, also in Australia, Doohan was fast again, but he’s delayed deciding which engine he will use until he can evaluate the latest versions back-to-back.

Yamaha is weaker than in the past, particularly since Wayne Rainey’s squad unexpectedly lost its Marlboro backing on the eve of the IRTA tests. Rainey also lost Marlboro’s support in recruiting a strong back-up to Japanese GP winner Norifume Abe, signing

Spanish 500-class novice Sete Gibernau instead. “We believed that we would have Marlboro support in 1997,” said Rainey. “Yamaha stepped in and has guaranteed us full support for the season. I am very grateful for the extra effort, and I know we’ll deliver the results.”

A second Yamaha team will run reigning World Superbike Champion Troy Corser and former 125 and 250cc World Champion Luca Cadalora. Despite crashing during testing in Malaysia, Corser is reportedly pleased with his progress. “I’m quite happy with my lap times, and the bike is getting better for me,” said the 25-yearold. “I made a small mistake on the last day and this resulted in my crashing. It was my mistake and I know what I did. I guess this is part of the learning process.”

Cadalora has been quick to acquaint himself with the new YZR500, as > well. “I am very excited by the way things are going,” he said. “I have tried many different chassis set-ups, and I feel more confident. I have a good base to work from and I am looking forward to the next round of tests.”

Suzuki is something of an unknown. Lead rider Daryl Beattie is back after missing most of last year due to injury. The Australian finished second to Doohan in ’95, but Beattie’s impetus after such a long layoff is in question. Suzuki also has Anthony Gobert, hot from winning both legs of the final round of last year’s World Superbike series in his Kawasaki swan song. Gobert will be an exciting addition to the grids, but he needs time to adapt to the power of a GP bike.

Which brings us to the others: Honda’s V-Twin debuted last year and almost won a race in the hands of development rider Tadayuki Okada. This year, Okada has moved to the VFour, his place taken by rising Japanese star Takuma Aoki. Incidentally, the expected flood of privateers on production versions of the NSR500V hasn’t materialized. Meanwhile, Aprilia’s Doriano Romboni is struggling from previous injuries; his future-and the RSV400’s-is uncertain.

This leaves Roberts and his all-new V-Three. Like the Twins, this project has the advantage of a lower weight limit (286 pounds for Fours, 253 pounds for Triples, 220 pounds for Twins). It is also an all-new machine, said to be highly “integrated” and very compact for good aerodynamics. The bike will be ridden by Kenny Roberts Jr. and Frenchman JeanMichel Bayle. It’s a tall order for a > new design to be competitive in its first year.

The 250cc class centers on whether three-time champion Max Biaggi can dominate now that he has switched from Aprilia to an Erv Kanemototuned, Marlboro Honda NSR250. Biaggi will face old rivals Loris Capirossi (back from the 500 class) and Tetsuya Harada (defected from Yamaha), who will ride the bikes upon which Biaggi achieved greatness.

Flex appeal

When it comes to chassis stiffness, designers are decidedly undecided, still being pushed this way and that by whatever hot trend comes along.

Now, these merry little breezes of fashion have assumed gale force. Honda’s latest NSR250 GP racer has its chassis stiffness reduced in almost all areas, its engine dangling from slender mounts. The steering-head area, formerly sheeted-in, now sports only a small crossmember. The regular GP teams are not uniformly happy with reduced stiffness. Max Biaggi, three-time 250cc world champion on an Aprilia, finds the Honda’s steering “heavy” and has been a second or more off the pre-season test pace. Yet Japanese rider Tohru Ukawa recently set a new Sugo lap record on an even more radical, experimental Honda with a “pivotless” chassis similar to that employed on the new VTR1000 streetbike. This machine’s swingarm pivots in the gearbox, Ducati-style, reminiscent of a Norton Isolastic chassis. Is chassis flex the answer? How much is too much?

Kawasaki, too, has experimented with varying stiffness levels, and even ran a Superbike equipped with a single-sided swingarm at a Laguna Seca winter test. Yamaha has trilled up and down the stiffness scale with different fork tube diameters, lengths of chassis top-plates and falling-rate suspension characteristics. Suzuki has built a rig to measure flexibilities in different directions. What’s going on here?

For race cars, it’s a simple truth that stiffer is better. Flex belongs only in the suspension, where it can be completely controlled by the dampers. Undamped flex in a chassis is a suspension within a suspension, the interaction of which produces unwanted, unpredictable motion.

Up to 1993, it looked as if the same was true of racing motorcycles. Making the chassis stiffer produced a real benefit; it moderated the wobbles of a fast, sliding corner exit, letting the suspension tame the horsepower of brutish 500cc GP engines.

Then, the trend fell apart. When a race car wheel hits a bump, it is pushed up vertically, the direction in which its suspension is designed to move. When the same happens to a bike in a corner, the bump still pushes vertically, but the suspension is leaned over with the bike. Something has to give, and it isn’t necessarily the suspension, because it’s almost sideways.

Before 1993, what flex was left in the fork tubes, steering head and swingarm was enough to absorb a useful percentage of in-corner bump action. But when the next stiffness level was reached, these bumps were no longer absorbed. Instead, the stiff chassis passed them straight on to the machine as a whole, knocking it about so badly that it could no longer hook up. >

It was a crisis. Describing his Yamaha YZR500 at the ’93 Australian GP at Eastern Creek, Wayne Rainey said it had “chatter, hop and skating.” Aprilia was (and still is) in the same boat.

The first “fix” was to reverse to earlier, flexier chassis, or to adopt falling-rate rear suspension curves, which get softer when compressed in a corner. Next task was to research the flex issue, and find out what works and what doesn’t.

One early result was the revised, flexier chassis of the ’96 Honda CBR900RR. While the previous, stiffer chassis had been criticized as too “busy,” the new chassis was supposedly much easier for even novice riders to confidently ride quickly. A major element in this de-stiffening program was to convert the swingarm pivot plates from box-beams to channel construction. Think of how much stiffness a box loses when you cut its top out and you grasp the concept.

Yamaha, too, made changes. Its ’96 TZ250 roadracer had much of its chassis side beams’ length converted from box to channel. Even before this, the race team had experimented with cutting out whole chassis members in search of the elusive “good flex.” What next, wire wheels?

Will simple chassis flex do the whole job, or will motorcycles need a “second suspension,” acting sideways, to handle bumps in corners? The late John Britten was working on this very problem. Although there may be an optimum level of chassis flex for a given bike on a given track, it will vary from track to track just as suspension settings do. Go too far with undamped flex and it gets a nasty new name: instability. Unless the flexure is concentrated in tunable chassis elements (urethane pads controlling steering-head and swingarm twist?), teams may need a different chassis at every track. This will get old quickly because changing chassis flex drastically changes suspension set-up.

Right now, the flaccid chassis is the hot trend, and everybody’s doing it. But trying to make a chassis do a suspension’s job will turn out to be a pinching compromise indeed. Something better has to come.

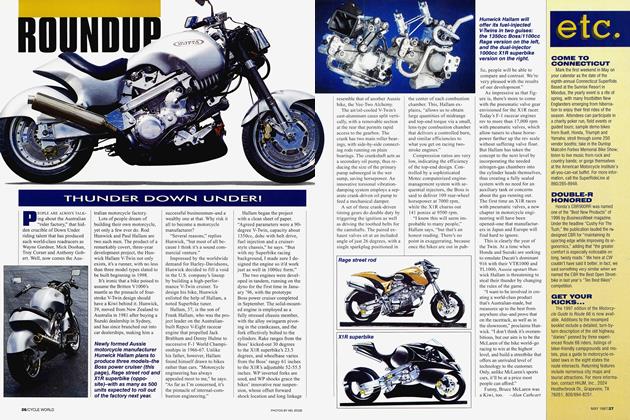

The return of Crocodile Ducatee

There have been three AMA National roadraces run at Phoenix International Raceway since 1993, and all have been won by Ducatis. Even weirder, the last two winners have been former Australian Superbike Champions. Coincidence? We think not.

Coming into this first round of the 1997 series, reigning U.S. Superbike Champion Doug Chandler identified his former Cagiva GP teammate Mat Mladin as a threat. Not only is the Aussie hugely talented, his Ducati wears Michelin tires, and the French rubber company will likely pull out all the stops to pry loose Dunlop’s stranglehold on the series.

The only question is the Italian bike’s reliability. But the Fast By Ferracci crew put paid to that concern at Phoenix as Mladin ran the same engine from Thursday on, only swinging a leg over his spare bike to scrub tires during Sunday morning’s warm-up.

Just as Troy Corser did in 1994, Mladin set a new track record to qualify on pole and then “checked > out” in the race, stretching his lead to a demoralizing 14 seconds before notching it back to win by 9.

Chandler headed the field into Turn 1 on his Muzzy Kawasaki, but he could only watch as Mladin drove past to grab the lead and headed for the horizon. The race was then processional, with the leaderboard unchanged until the very last lap, when ’95 champ Miguel Duhamel stuffed past Chandler on the brakes to claim the runner-up spot on his Smokin’ Joe’s Honda. Yoshimura Suzuki pilot Pascal Picotte nipped Harley-Davidson’s Thomas Wilson for fourth.

The race to watch, though, was 600cc Supersport. With 20 riders receiving factory support, the racing was guaranteed to be close, and it was.

But although young upstarts threatened-new Kinko’s Kawasaki signing Jamie Hacking qualified on pole and led, and 18-year-old Muzzy Kawasaki rider Tommy Hayden ran with the lead pack before falling—it was the familiar names of Picotte, Aaron Yates and Duhamel who climbed the victory podium in the end.

As foreboding as Suzuki’s 1-2 finish looks, however, Duhamel isn’t too worried about 600cc Supersport becoming a one-horse race-especially as Honda riders Ben Bostrom, Steve Crevier and Andrew Stroud followed him across the finish line.

“All the way to the last corner, it was anyone’s race,” Duhamel said. “I think it’s going to be this kind of racing all year.”

Let’s hope so. >

Supercross super season

With five of 15 rounds complete, this is shaping up to be one of the most unpredictable AMA Supercross seasons yet.

Yamaha’s Doug Henry is in top form after an inspiring recovery from a near career-ending back injury two years ago. Consistency is the key to winning championships, and Henry is leading the points chase with two wins, a second, a third and a sixth. Word has it that Henry is considering racing Yamaha’s works YZM400 Thumper in Supercross competition, possibly at the Daytona and Minneapolis rounds.

Outdoor title holder Jeff Emig was the only rider to give Jeremy McGrath a run for his money last year. Wins in Phoenix and Indianapolis have put the Kawasaki-mounted Californian in second overall.

A trio of top-three finishes in Los Angeles, Phoenix and Seattle hinted that McGrath is back on track. In Indianapolis, though, the King of Supercross fizzled, placing a disappointing ninth on his semi-factory Suzuki. Still, the four-time champ is fourth in points behind Honda of Troy’s Larry Ward. Factor in McGrath’s Suzuki teammates Greg Albertyn and Mike LaRocco, newly unretired Mike Kiedrowski and “The Beast from the East,” Damon Bradshaw, and there’s no telling how the season may end. O