THE BIG CHILL

RACE WATCH

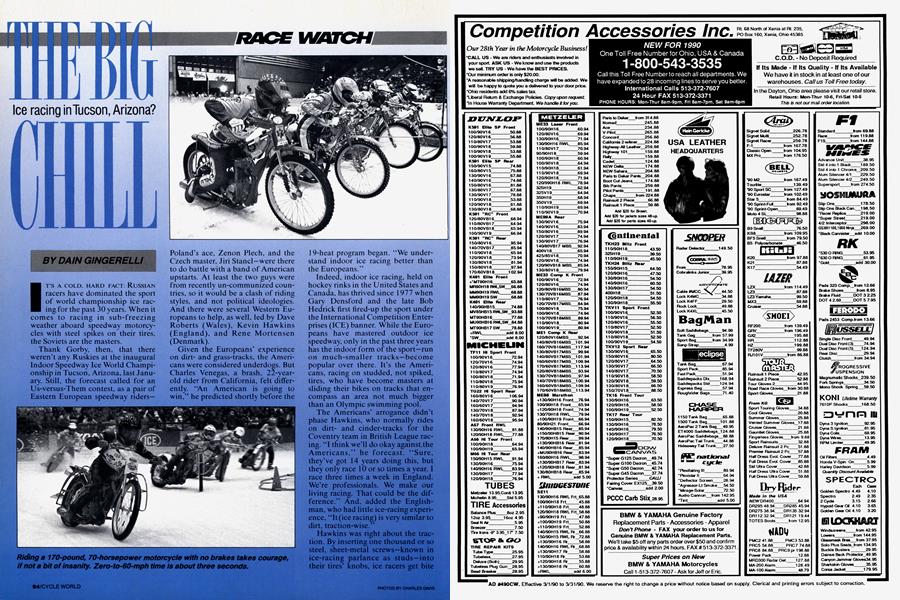

Ice racing in tucson, Arizona?

DAIN GINGERELLI

IT'S A COLD, HARD FACT: RUSSIAN racers have dominated the sport of world championship ice racing for the past 30 years. When it comes to racing in sub-freezing weather aboard speedway motorcycles with steel spikes on their tires, the Soviets are the masters.

Thank Gorby, then, that there weren’t any Ruskies at the inaugural Indoor Speedway Ice World Championship in Tucson, Arizona, last January. Still, the forecast called for an Us-versus-Them contest, as a pair of Eastern European speedway riders— Poland’s ace, Zenon Plech, and the Czech master, Jiri Stand—were there to do battle with a band of American upstarts. At least the two guys were from recently un-communized countries, so it would be a clash of riding styles, and not political ideologies. And there were several Western Europeans to help, as well, led by Dave Roberts (Wales), Kevin Hawkins (England), and Rene Mortensen (Denmark).

Given the Europeans’ experience on dirtand grass-tracks, the Americans were considered underdogs. But Charles Venegas, a brash, 22-yearold rider from California, felt differently. “An American is going to win,” he predicted shortly before the 19-heat program began. “We understand indoor ice racing better than the Europeans.”

Indeed, indoor ice racing. held on hockey rinks in the United States and Canada, has thrived since 1977 when Gary Densford and the late Bob Hedrick first fired-up the sport under the International Competition Enter prises (ICE) banner. While the Euro peans have mastered outdoor ice speedway, only in the past three years has the indoor form of the sport-run on much-smaller tracks-become popular over there. It's the Amen cans, racing on studded, not spiked, tires, who have become masters at sliding their bikes on tracks that en compass an area not much bigger than an Olympic swimming pool.

The Americans’ arrogance didn’t phase Hawkins, who normally rides on dirtand cinder-tracks for the Coventry team in British League racing. “I think we’ll do okay against the Americans,” he forecast. “Sure, they’ve got 14 years doing this, but they only race 10 or so times a year. I race three times a week in England. We’re professionals. We make our living racing. That could be the difference.” And, added the Englishman, who had little ice-racing experience, “It (ice racing) is very similar to dirt, traction-wise.”

Hawkins was right about the traction. By inserting one thousand or so steel, sheet-metal screws—known in ice-racing parlance as studs—into their tires’ knobs, ice racers get bite that is about equal to what a standard tire on dirt would provide. But Hawkins failed to consider one other aspect: As the racing progresses on dirt tracks, a “groove” develops that dictates the optimum line through the corners, which in turn reduces the amount of passing in a race. An experienced rider knows this, and plans his race strategy accordingly, sometimes waiting for two or three laps to make a move on an opponent.

Things are different on ice. As the riders slide through the corners, the surface merely gets shaved off, so traction remains consistent throughout the evening. Result: Ice racing is furious and unpredictable, making passing among the riders the norm, rather than the exception. The rider who matches technique with courage stands the best chance of winning. The bottom line is that indoor speedway ice racing is among the mostcompetitive forms of motorcycle racing in the world.

For the most part, speedway ice racers are nothing more than modi fied Class A speedway bikes. Like their dirt cousins, the ice bikes are basedon a design that dates back to the Depression era. Heartbeat of the motorcycle is a single-cylinder, 500cc four-stroke engine. The only suspension is the fork's 3 inches of travel, and there are no brakes.

Despite their somewhat cocky attitude, the Americans rolled their bikes into the Tucson Convention Center ice arena fully expecting trouble from their European counterparts. But as the track announcer introduced the American riders to the partisan crowd, confidence grew. The Americans were led by 1988 ICE National Champion George “Lazer Beam” Lazor, of New York, ’87 champ Mark Borgman from Colorado, Canadian titlist (but New Yorknative) Warren “The Warrior” Diem and Californian Robert “Kid” Curry, who had won events in Portland and Sacramento. They were backed by a throng of others who had sound ice-racing experience.

International courtesy dictated that the Europeans did not have to participate in two days of qualifying races prior to Saturday night’s final: Jhey automatically were seeded, meaning they could save their bikes and bodies for the last evening of racing. Ironically, this might have> worked against them, because each rider got only four laps of practice before Saturday night's bash, cer tainly not enough time to develop a riding style. let alone properly set up equipment. or even figure out the best tire-stud pattern.

Within the first four heats, the Americans started to dominate. It wasn't until heat nine that the Dane, Mortensen, broke the ice, so to speak, leading Americans Venegas and Borgman, as well as England’s Hawkins, across the line. Later, in heat 14, Hawkins again put the Americans on ice, for the second of only two Euro wins.

Other than Hawkins, who demon strated nicely controlled slides, the Europeans were, literally and figura tively, out in the cold. Stand and Plech, in particular, looked wobbly through the corners, resembling Nov ice riders and showing a reluctance to spin their rear wheels on the unfamil iar surface. As any ice-speedway vet eran will attest, if you don't spin the rear wheel through the corner, the bike will stand up and head directly for the outside retaining wall.

So, while most of the old-world riders fought the plywood, the Colonials continued to rack up points, until Hawkins was the only foreigner who stood a chance of making the main event. And it was the main—a> six-lap, six-rider affair—that determined who would be ICE world champion.

At the end of 16 heats, two semis and one last-chance qualifier, the half-dozen with a shot at the title were Diem, on the pole, joined by Venegas and Scott Ormiston on the front row, while Curry, Pat “The Rat” Litt and Hawkins filled out the back row.

Taking advantage of his starting position. Diem got the holeshot and charged into the lead. Ormiston managed to challenge on the second lap, and the two diced for three laps, with Ormiston assuming the lead on lap four after a daring move.

But it was for naught. As Ormiston recalled after the race, “I just came in too hot, and he got me.” At the end, it was Diem leading Ormiston, Curry, Hawkins, Litt and then Venegas in the first-ever Indoor Ice Speedway World Championship.

After accepting his crystal trophy and $1500 first-place money, Diem said that he was unsure about how good his traction would be before the race. Earlier in the evening, other riders had questioned the legality of the studs he used on Friday, so before Saturday’s championship. Diem changed all 1000 steel screws in his tires. “I stuck with my pattern, but changed my studs to a shorter kind,” he revealed.

It paid off, and on the victory podium, Diem remarked about his winnings, “I have to pay for them studs somehow.” Chances are that he’ll have a few bucks left over to defend his title next year, too. Eâ

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

April 1990 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

April 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

April 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupMichelin Pulls Out of U.S. Bike-Tire Market

April 1990 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

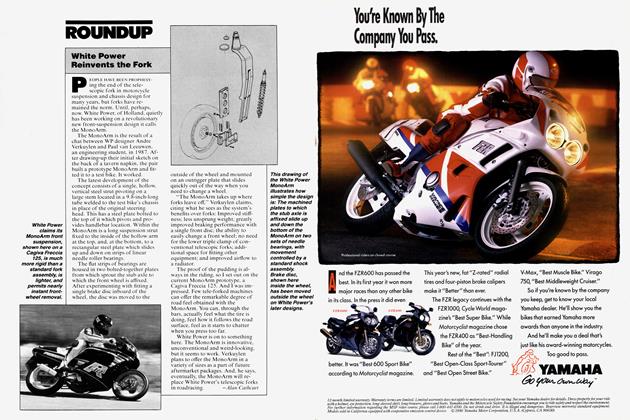

RoundupWhite Power Reinvents the Fork

April 1990 By Alan Cathcart