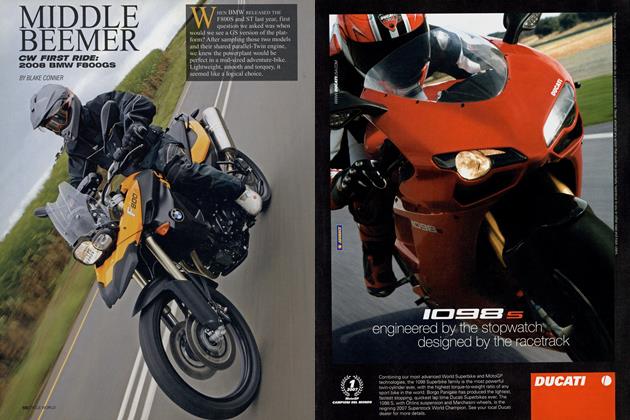

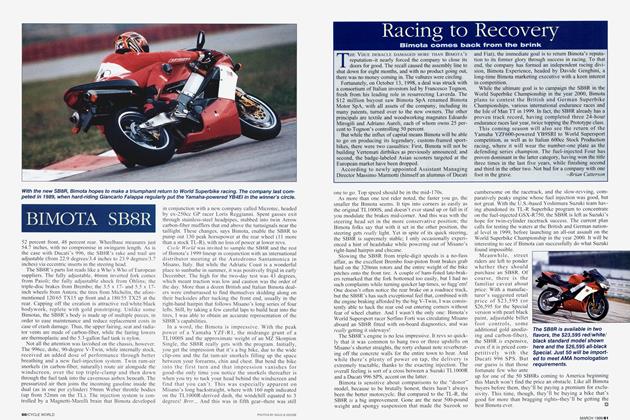

900 SPRINT: TRIUMPH'S MISSING LINK

TRIUMPH IS CONCERNED. AREN'T FOUR-CYLINder motorcycles, well, Japanese? And aren't Triples undeniably British? Rather, old chap. Just ask any enthusiast who witnessed the sales strife, and resulting enthusiast blather, in the late 1960s when Triumph's Trident competed against Honda's 750 Four.

As it happens, through the wonders of modular engineering, today’s Triumph finds itself pretty much able to build anything it wants. It’s got Triples and Fours, standard bikes, sport-tourers and full-on sportbikes. What it doesn’t have (make that didn’t have...) is a crossover bike, an intermediate machine that touched the bases between the unfaired, standard-style Trident and its hardcore, full-fairing models.

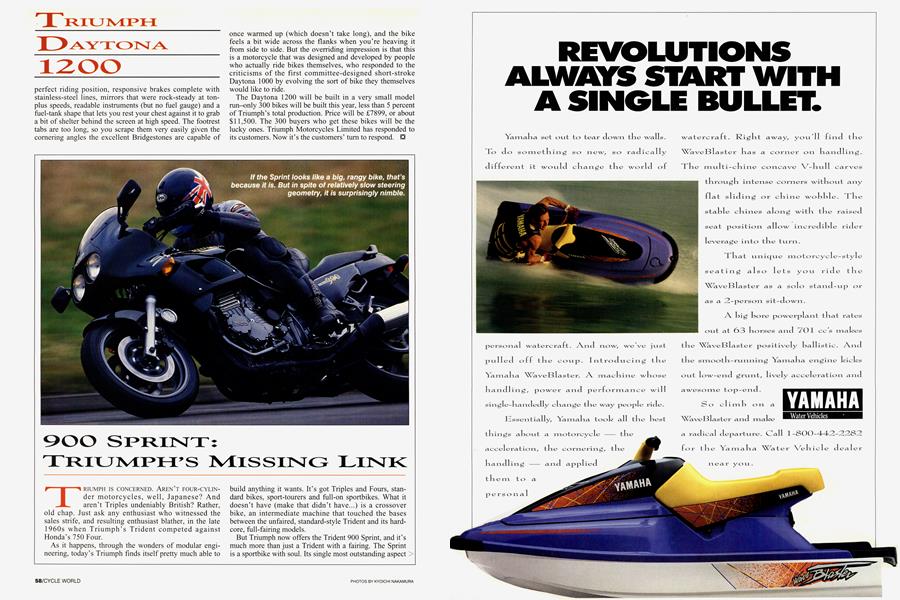

But Triumph now offers the Trident 900 Sprint, and it’s much more than just a Trident with a fairing. The Sprint is a sportbike with soul. Its single most outstanding aspect is its wonderful engine, one of the most emotive and individual engineering experiences currently available on two wheels. There’s nothing else like it on the market: that muted boom from the exhaust, the distinctive whir of the 120-degree engine with its chain-driven balance shaft, the invigorating rasp as you crack the slightly stiff throttles wide open to release oceans of torque.

Triumph wisely has endowed the Sprint with nimbleness to match that wonderful engine, doing so by hanging premium suspension bits from either end of the standard backbone frame used by all the bikes in its line. The Sprint’s Kayaba front fork comes with dual-rate springs and is adjustable for compression damping. It would be nice if the bike wore the full-spec Kayaba fitted to the Daytona, which is adjustable for rebound as well. The shock is the same multi-adjustable Kayaba used on the Trophy; some fiddling here allows the bike to be nicely dialed-in. The Sprint is so fond of cornering that it’s easy to ground the bike’s footpeg tabs, thanks in part to the terrific traction available from the Michelin radiais fitted as standard equipment. The kicked-out steering geometry (a 27-degree head angle, and 4.1 inches of trail, matched to a 58.6-inch wheelbase) is wellsuited to the Sprint, especially with the wide-spread bars giving extra leverage where necessary.

On winding country lanes, though, many riders will wish for a more sporting riding stance. As it is hustled through turns, the Sprint feels a little remote because you’re sitting on the bike, but don’t quite feel part of it. The Nissin brake system also isn’t quite up to par. It uses the same twin-piston calipers as the Trophy/Trident machines, not the four-piston units of the Daytona. This really is a pity, because though the junior-version Nissins are okay for the job on a bike weighing a claimed 474 pounds, they’re only marginally so.

The Sprint’s upright riding position is great around town, where the wide bar gives good leverage for sharp turns. It’s also surprisingly comfortable on the freeway, where the small fairing does its job well.

If the Sprint is mainly a success on the move, it’s a sure-fire hit at rest. This comes in great measure because of the bike’s curvy, just-right styling and its quality finish. The paintwork is superb, and the lustrous slate-gray engine emphasizes Triumph’s work in cleaning up the design by removing several of the external lines and pipes that formerly ran around it.

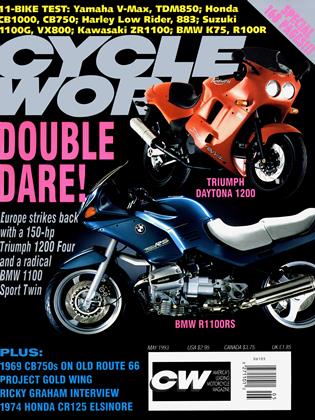

The Triumph Sprint’s competition? Might be Ducati’s 900SS. But more likely it’s the Sprint vs. the born-again R1100RS Boxer. But whether you favor British, Italian or German machinery, the Triumph Trident is further proof that when it comes to motorcycles, Europe is back in a big way.

Alan Cathcart

View Full Issue

View Full Issue