Just Add Horsepower

American bicycle-maker Cannondale gears up for motorcycle production

KEVIN CAMERON

THE CANNONDALE OFF-ROAD MOTORCYCLE HAS EMERGED! Over the past year it has seemed near enough to touch, but has slipped away. Rumors have flowed. Now we’ve seen it and CW's Off-Road Editor Jimmy Lewis has ridden it.

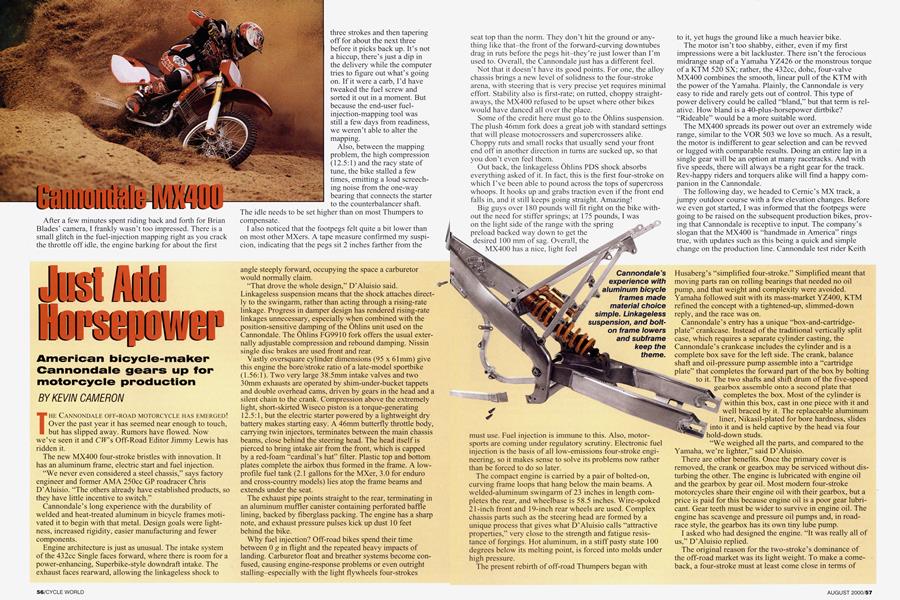

The new MX400 four-stroke bristles with innovation. It has an aluminum frame, electric start and fuel injection.

“We never even considered a steel chassis,” says factory engineer and former AMA 250cc GP roadracer Chris D’Aluisio. “The others already have established products, so they have little incentive to switch.”

Cannondale’s long experience with the durability of welded and heat-treated aluminum in bicycle frames motivated it to begin with that metal. Design goals were lightness, increased rigidity, easier manufacturing and fewer components.

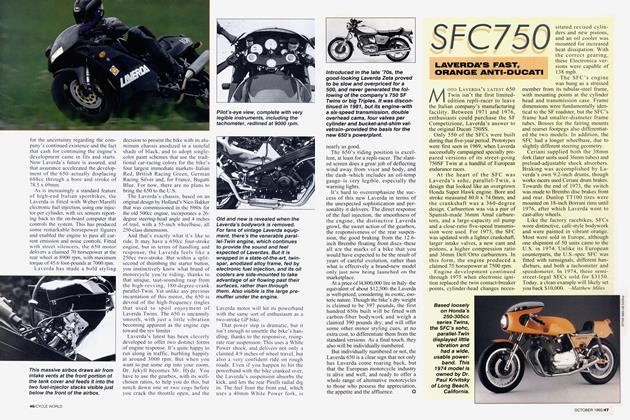

Engine architecture is just as unusual. The intake system of the 432cc Single faces forward, where there is room for a power-enhancing, Superbike-style downdraft intake. The exhaust faces rearward, allowing the linkageless shock to angle steeply forward, occupying the space a carburetor would normally claim.

“That drove the whole design,” D’Aluisio said. Linkageless suspension means that the shock attaches directly to the swingarm, rather than acting through a rising-rate linkage. Progress in damper design has rendered rising-rate linkages unnecessary, especially when combined with the position-sensitive damping of the Öhlins unit used on the Cannondale. The Öhlins FG9910 fork offers the usual externally adjustable compression and rebound damping. Nissin single disc brakes are used front and rear.

Vastly oversquare cylinder dimensions (95 x 61mm) give this engine the bore/stroke ratio of a late-model sportbike (1.56:1). Two very large 38.5mm intake valves and two 30mm exhausts are operated by shim-under-bucket tappets and double overhead cams, driven by gears in the head and a silent chain to the crank. Compression above the extremely light, short-skirted Wiseco piston is a torque-generating 12.5:1, but the electric starter powered by a lightweight dry battery makes starting easy. A 46mm butterfly throttle body, carrying twin injectors, terminates between the main chassis beams, close behind the steering head. The head itself is pierced to bring intake air from the front, which is capped by a red-foam “cardinal’s hat” filter. Plastic top and bottom plates complete the airbox thus formed in the frame. A lowprofile fuel tank (2.1 gallons for the MXer, 3.0 for enduro and cross-country models) lies atop the frame beams and extends under the seat.

The exhaust pipe points straight to the rear, terminating in an aluminum muffler canister containing perforated baffle lining, backed by fiberglass packing. The engine has a sharp note, and exhaust pressure pulses kick up dust 10 feet behind the bike.

Why fuel injection? Off-road bikes spend their time between 0 g in flight and the repeated heavy impacts of landing. Carburetor float and breather systems become confused, causing engine-response problems or even outright stalling-especially with the light flywheels four-strokes must use. Fuel injection is immune to this. Also, motorsports are coming under regulatory scrutiny. Electronic fuel injection is the basis of all low-emissions four-stroke engineering, so it makes sense to solve its problems now rather than be forced to do so later.

The compact engine is carried by a pair of bolted-on, curving frame loops that hang below the main beams. A welded-aluminum swingarm of 23 inches in length completes the rear, and wheelbase is 58.5 inches. Wire-spoked 21-inch front and 19-inch rear wheels are used. Complex chassis parts such as the steering head are formed by a unique process that gives what D’Aluisio calls “attractive properties,” very close to the strength and fatigue resistance of forgings. Hot aluminum, in a stiff pasty state 100 degrees below its melting point, is forced into molds under high pressure.

The present rebirth of off-road Thumpers began with Husaberg’s “simplified four-stroke.” Simplified meant that moving parts ran on rolling bearings that needed no oil pump, and that weight and complexity were avoided. Yamaha followed suit with its mass-market YZ400, KTM refined the concept with a tightened-up, slimmed-down reply, and the race was on.

Cannondale’s entry has a unique “box-and-cartridgeplate” crankcase. Instead of the traditional vertically split case, which requires a separate cylinder casting, the Cannondale’s crankcase includes the cylinder and is a complete box save for the left side. The crank, balance shaft and oil-pressure pump assemble into a “cartridge plate” that completes the forward part of the box by bolting to it. The two shafts and shift drum of the five-speed gearbox assemble onto a second plate that completes the box. Most of the cylinder is within this box, cast in one piece with it and well braced by it. The replaceable aluminum liner, Nikasil-plated for bore hardness, slides into it and is held captive by the head via four hold-down studs.

“We weighed all the parts, and compared to the Yamaha, we’re lighter,” said D’Aluisio.

There are other benefits. Once the primary cover is removed, the crank or gearbox may be serviced without disturbing the other. The engine is lubricated with engine oil and the gearbox by gear oil. Most modem four-stroke motorcycles share their engine oil with their gearbox, but a price is paid for this because engine oil is a poor gear lubricant. Gear teeth must be wider to survive in engine oil. The engine has scavenge and pressure oil pumps and, in roadrace style, the gearbox has its own tiny lube pump.

I asked who had designed the engine. “It was really all of us,” D’Aluisio replied.

The original reason for the two-stroke’s dominance of the off-road market was its light weight. To make a comeback, a four-stroke must at least come close in terms of power-to-weight ratio, and then make up any lack in that department through a better powerband. That means saving weight every way possible. Brochure weight of the Cannondale MX400 is 242 pounds. Output is quoted as 47 horsepower, with peak torque in the 7000-8000-rpm range. Maximum revs are 11,500, so the powerband is generous.

As an example of weight-saving detail, small 52mm OD main bearings are used on the crankshaft, rather than the 62 or even 72mm used on older designs. Shift drum and fork rails (hard-anodized) are aluminum; even the output sprocket nut is aluminum. Parts have been slimmed wherever possible; the smooth and attractive engine castings are of very thin and uniform section, produced by a zero-draft sand-casting process.

A central feature of all the new off-road four-strokes is-and has to be-undersized flywheels. Off-road four-strokes of the 1950s had giant flywheels to allow a slow idle and ensure smooth low-speed pulling. Thirty-pound millwheels are now an impossible luxury, so the new-generation fourstrokes have tiny short-stroke crankshafts appropriate to their nearly doubled rpm capability.

A major part of Cannondale engineering, in both bicycle and motorcycle divisions, is durability testing. With human testers, it’s practically impossible to give a new bicycle 10 years of test use before it goes on the market-but surprise failures in the field can instantly kill a new product. Therefore, accelerated durability testing is necessary. Cannondale’s test labs reverberate with the maddening, repetitive snick-snack sound of pneumatic cylinders applying constantly reversing loads to various components. The ceiling of one lab hangs with the collapsed chassis of a variety of other makes. Information!

Scientific durability testing means placing strain gauges on competitors’ chassis, then subjecting the bikes to normal offroad-maneuver severity while recording the resulting deflections. These real-world-recorded stresses can then be duplicated in lab rigs that can, by running day and night,

realistically test future designs in only days or weeks. Without such testing, products would hit the market with too many unknowns. Business is always a gamble, but successful gamblers want to know the odds.

Over lunch, I had the opportunity to talk with Cannondale owner Joe Montgomery. The classic self-made American executive, Montgomery was dressed in white shirt and suit trousers but no coat, and cowboy boots. He had flown in that morning, personally piloting his Cessna biz-jet. The main thing I wanted to know was, “Why are you doing this?” His reply was more cowboy boots than business suit: “We wanted to.”

He elaborated, saying, “We’ve handled a lot of challenges in the bicycle business, but now it’s settling down a bit. We needed a fresh challenge.”

The new motorcycle manufacturing plant didn’t exist a year ago. It is impressively large and filled with everything needed to develop, test and manufacture motorcycles. It is located in a town called Bedford, in a dense manufacturing area of Pennsylvania, and on nearby highways the snore of heavy trucks carrying castings, stampings and metal coil continues day and night. As I got to know Montgomery better, and talked with his engineers in the afternoon, I realized that they have improvised their way to success more than they have planned it in detail.

The Cannondale motorcycle plant is the complete antithesis of automated mass production. That big decal on the swingarm proclaiming “Handmade in America” is the literal truth. Chassis elements are taken from racks to individual welding cells in which skilled human welders (women are prominent in Cannondale’s plants) perform the joining. Engines are assembled as sub-units at individual workstations-the crank group, gearbox group and so on. Assemblers work at benches or fixtures, taking parts from racks of bins. Finally, the sub-units are brought together as complete engines. Meanwhile, chassis are assembled in individual building cells—there is no production line per se. All this would look very much like manual assembly in the Indian plant in 1911, except for certain important details. One is that Ingersoll-Rand runner-torquer-sequencers are used to drive all threaded fasteners. These hand-held devices are linked to a computer that makes sure the fasteners are used in the proper sequence and are properly tightened. They also count the number of revolutions each one makes to be sure that no threads are pulled, no fastener is stopped short. A production engineer with whom I discussed this pointed out the value of limiting tooling expense early in the history of a new product. Also, assembly by individual people trains an inner group of experts who learn far more than how to insert Bolt A into Hole C. Valuable now, this will become even more valuable later. Given Cannondale’s history of manufacturing improvements on the bicycle side, we can expect production streamlining to occur as needed, as everyone grows more familiar with the product and process.

Later in the day, we drove to a nearby motocross track to see the bike run in its natural habitat. A number of bikes-including zero-timers assembled that moming-were ridden by both Cannondale testers and Lewis. These bikes have clearly reached an acceptable level of reliability because many engine-hours were run up and there were no problems beyond a flat tire.

I believe that much of Cannondale’s confidence comes from its history of successful problem solving. Beyond that, a worldwide trend toward local manufacturing can be seen. Even though Japanese factories achieve economies of scale and have great accumulated experience, independent specialist makers such as KTM have emerged. These companies succeed because they are small and agile, and are close to their markets. Their success must encourage Cannondale which, being here in the U.S., can closely tailor its product to what American riders want, thereby arguably making it uniquely appealing. Cannondale’s strategy is to get market attention with a feature-laden machine, then evolve optimum manufacturing strategy over the life of the product.

I suspect its ambition doesn’t end with this bike. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontNed's Sled

August 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsCharacter Infusion

August 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCTwo Crankshafts?

August 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

August 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupEurope Gets Naked!

August 2000 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupIndian's Sporting Scout

August 2000 By Wendy F. Black