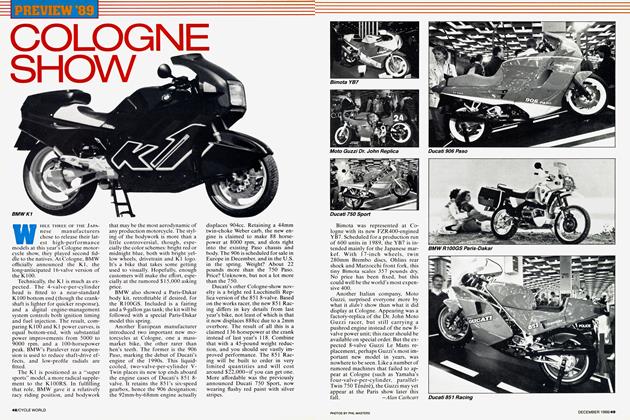

Sound of Singles

RACE WATCH

Welcome to the world of fast, far-out Thumpers

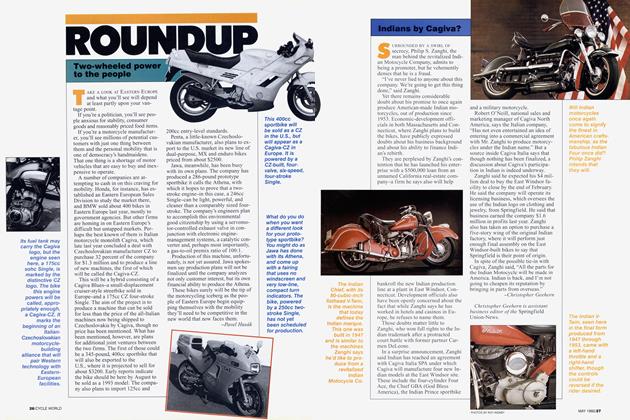

AS RECENTLY AS FIVE YEARS AGO, single-cylinder roadracing conjured up mental images of nostalgia freaks clad in black leathers attempting to relive their collective youth aboard a selection of rapidly appreciating British and Italian museum pieces. Half a decade later, it’s a worldwide phenomenon, an ultra-competitive category for increasingly sophisticated machines.

Sound of Singles, as the class has come to be called, attracts a great variety of marques to what is effectively a four-stroke GP class. So successful is SoS, in fact, that it is threatening to surpass its close cousin, the Battle of the Twins, in worldwide popularity.

ALAN CATHCART

Overstatement? Hardly. Count the makes: Cagiva, Gilera, Husaberg, Husqvarna, KTM, Matchless and Villa, plus the Japanese Big Four, are already represented in SoS racing, with more to come as enthusiasm for the class catches on. Ducati is hard at work on a modern desmo Single, thanks to the way SoS has taken off.

Sophistication? Everything your techno-addict’s heart could wish for, from aluminum-honeycomb composite chassis to full-monocoque designs to ultra-light, beautifully welded tubular spaceframes. Engines? The range is enormous, from liquid-cooled, dohc, four-valve designs like the Gilera to air-cooled twovalves like Mick Rutter’s born-again Matchless G50based ERM motors to the air/oil-cooled Suzuki DR Big to reworked speedway engines. You name it, SoS has it, with the only common element being the basic four-stroke,

one-cylinder, anything-else-goes philosophy. This is the way BoTT started out, as a breeding ground for the fertile imagination of the home engineer. Except that as Twins racing became more popular, the factories got involved, and now you have to have electronic fuel injection and a computerized engine-management system if you’re to stand a chance.

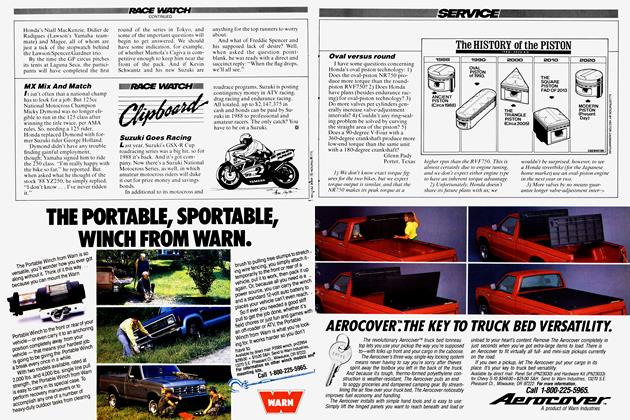

Like many new racing formulas, the SoS concept originated in Britain, as long ago as 1973 when the Bemsee club started running a 250cc Singles class as a refuge for Aermacchis, Ducatis and the British and Spanish two-stroke Singles that had been shoved out of contention by the Yamaha TDs and their kin. The concept was so successful that the club started a separate 500cc class, which other clubs copied and which in 1978 evolved into a full-blown British National series sponsored by Kennings Tires.

But there was one important difference: The Kennings series’ organizer, Paul Franklin-who in many ways can

be considered the father of SoS-was enlightened enough to open the races to four-stroke Singles of any age and provenance. Since the Japanese manufacturers recently had discovered the four-stroke Single, producing bikes like the Yamaha SR500 and Honda XR500, Franklin’s was a farsighted decision that encouraged a number of people to build bikes around these en-

gines. The result was a fascinating duel between one-off modern machines and established British Singles like the Norton Manx and Matchless G50, which came out of the wood-

work for the new series. Initially, the two types of bikes were very closely matched, and the battles for supremacy between Robin Riley’s Hagon Honda (featuring an aluminumalloy monocoque chassis that was a foretaste of the creative technology to come in the class) and Malcolm Lucas’ Petty Manx provided gripping viewing for onlookers in the late ’70s.

But all was not well. In the days before the present flourishing remanufactured parts industry, resentment against the enduro-engined modern racers took hold on the part of the> classic brigade, who might find themselves sidelined for the rest of the season after overstressing an engine in battle with the younger bikes. In due course, the Kennings series was restricted to historic racers only.

This left modern Singles out on a limb. But the success of the original Kennings series had not gone unnoticed elsewhere. In 1980, the FIM proposed an abortive “European Clubmans Championship” for singlecylinder four-strokes. And in Japan, the growing popularity of street Singles in the early ’80s encouraged a handful of forward-thinking organizers to start running races for lightly modified roadsters. The Japanese organizers were soon inundated with entries, encouraging them to structure an Open> GP class for purpose-built racers, and coining the evocative name by which the class would become known around the world: Sound of Singles.

I went to my first SoS meeting in Japan in 1986, and was literally stunned by what I saw. More than 200 bikes were split into three different classes, with thinly disguised works entries from Honda and Yamaha (which dominated in the class then and now) among a host of imaginatively engineered machines. Reports of such events awoke Europeans to the potential of the Singles class as a relatively inexpensive form of roll-yourown racing, and an inaugural race for SoS machines was held in Germany at the end of 1988. This proved to be so successful that a full series was staged in 1989 (won by a quasi-works KTM 500 four-valve special) which, in turn, was so well supported that the class achieved full German title status for a 10-round series in 1991.

This encouraged other nations to give the class a tryout, especially in Italy, where the first event was held at Monza in 1989 (won by a modern works Gilera Saturno), leading to an eight-race championship for 1991. Other countries will surely follow suit in short order; for once, the FIM appears to have been ahead of the game in proposing its Clubmans series a decade ago. Is now the time to renew the initiative?

The appeal of Sound of Singles isn’t hard to decipher. As the class name suggests, there’s an undeniable attraction to the mellifluous noise that a free-breathing, lightly muffled onelunger creates. Also, the ready availability of a wide choice of engines mostly sourced from the off-road world, with commensurate spare parts availability, makes building your own SoS racer an attainable dream. This is especially true if you opt to use one of the wide range of aftermarket frames available, rather than build your own. There’s almost a century of accumulated tuning knowledge in how to develop the performance of singlecylinder engines, which respond well to the traditional techniques of raising compression, boring the cylinder, fitting high-lift camshafts and oversize valves, and slashing weight whenever possible. With performance similar to current 125cc GP bikes (SoS racers are more powerful, but also heavier), the racing is fast enough to be exciting, the bikes are closely matched enough to thrill, but at the same time, reliable enough to permit a full season

of 10 races on a single engine rebuild and a few sets of tires-just like the Norton Manx-mounted GP riders of two decades ago.

The wheel has come full circle, then, but with the important distinetion that where our golden-oldie Manxman found his bike eventually rendered hopelessly uncompetitive by the advent of the first four-stroke Multis, then by the modern twostrokes, the Sound of Singles by definition can suffer no such fate. If a restriction on fuel injection is implemented, there seems no reason why a bike that’s competitive today shouldn’t be so 10 years from now.

With SoS now firmly established with well-supported events in Japan, Italy, France, Germany, Flolland, Britain and Austria, and Spain and France joining in this year, Singles racing has taken firm root at the national as well as the international level. The two major European events in 1991, at Monza and Assen, saw riders from a dozen countries vying for honors, with Japanese champion Shinichiro Oura scoring an upset victory on the alloy-spaceframe Over Yamaha SRX-6 at Assen, while GP guru Roberto Gallina’s son, Michele, took a last-corner win in the highspeed Monza chase aboard his dad’s Suzuki DR-powered machine (see “Gallina Supermono”, page 96).

With all this worldwide action, it seems little short of amazing that America hasn’t discovered SoS yet, in spite of the dedicated efforts of Ron Wood and a handful of like-minded men. With the amalgamation of the Pro-Twins GP1 and GP2 classes into a single SuperTwins class for 1992, the space is there in the AMA race program, especially at Daytona, which would attract riders from all over the world to set new records for the fastest single-cylinder race yet run. Maybe in 1993? □