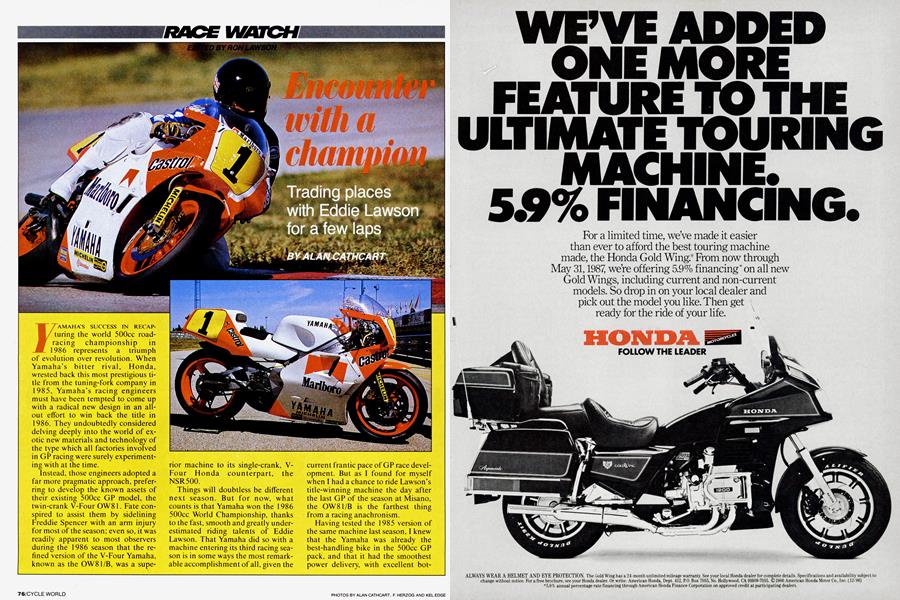

Encounter with a champion

RACE WATCH

Trading places with Eddie Lawson for a few laps

ALAN CATHCART

RON LAWSON

YAMAHA’S SUCCESS IN RECAPturing the world 500cc road-racing championship in 1986 represents a triumph of evolution over revolution. When Yamaha’s bitter rival, Honda, wrested back this most prestigious title from the tuning-fork company in 1985, Yamaha’s racing engineers must have been tempted to come up with a radical new design in an all-out effort to win back the title in 1986. They undoubtedly considered delving deeply into the world of exotic new materials and technology of the type which all factories involved in GP racing were surely experimenting with at the time.

Instead, those engineers adopted a far more pragmatic approach, preferring to develop the known assets of their existing 500cc GP model, the twin-crank V-Four OW81. Fate conspired to assist them by sidelining Freddie Spencer with an arm injury for most of the season; even so, it was readily apparent to most observers during the 1986 season that the refined version of the V-Four Yamaha, known as the OW81/B, was a superior machine to its single-crank, VFour Honda counterpart, the NSR500.

Things will doubtless be different next season. But for now, what counts is that Yamaha won the 1986 500cc World Championship, thanks to the fast, smooth and greatly underestimated riding talents of Eddie Lawson. That Yamaha did so with a machine entering its third racing season is in some ways the most remarkable accomplishment of all, given the current frantic pace of GP race development. But as I found for myself when I had a chance to ride Lawson’s title-winning machine the day after the last GP of the season at Misano, the OW81/B is the farthest thing from a racing anachronism.

Having tested the 1985 version of the same machine last season, I knew that the Yamaha was already the best-handling bike in the 500cc GP pack, and that it had the smoothest power delivery, with excellent bottom-end and mid-range power. Where it lost out to the Honda that year was in maximum power and top speed.

Those deficiencies must have formed the basis of Yamaha’s winterdevelopment program. The engineers retained the twin, counter-rotating crankshaft layout —which juxtaposes the two pairs of cylinders at a 70-degree included angle—and made only slight modifications to the 35mm, twin-throat, magnesium-bodied Mikuni carbs that sit between the cylinder banks. They did, however, fiddle quite a bit with the pipes and the cylinder porting in an effort to gain more horsepower without sacrificing ridability.

In basic layout, the porting is the same as it was in ’85, with four side transfer ports and two rear ones, plus one main exhaust port and a pair of boost ports. The exhaust is, of course, fitted with a YPVS variable-port-timing system, usingguillotine-type slide valves electrically operated via cables and a small, lithium-battery-powered motor that gets its open/close signals from the tachometer. Induction is through reed valves that feed directly into the crankcase, and ignition is by a conventional CDI system, with the generator located on the bottom pair of cylinders and the trigger mechanism on top on the left.

The ’85 version of this bike had what felt like the widest powerband ever offered by a modern, 500cc twostroke factory racer. It would pull cleanly from as low down as 6500 rpm, and had good, usable power from just over 8000 revs, with a peak output of 142 bhp at 12,000 rpm. But the claimed output for the '86 bike was up to 145 bhp, while keeping the same maximum-rpm limit.

Clearly, Lawson’s Yamaha was quicker than any other bike down the Mistrale Straight at Paul Ricard in the French GP in '86, including the NSR Hondas. At Misano, I learned why. Pussyfooting around for the first couple of laps, I found that while the OW still pulls reasonably well from very low down, you really have to get a good bit above 9000 rpm before the anticipated herd of fire-eating, title-winning horses arrives. But when they do, especially in the lower three gears, you'd better have your weight hard over the bars to keep the front wheel at least in intermittent contact with the ground, and you had also better hold on tight.

Despite that, the power delivery is impressive rather than daunting, unlike the NSR500 Honda, on which I found it all too easy to snap the back wheel out of line just by opening the throttle too fast and too far at the wrong moment. On the Yamaha, there's a strong rush of power at about 9300 revs up to around 10,500; but from that point upwards, there is a sort of hyper-powerband that has you frantically speeding up your thought processes just to cope.

Actually, because the Yamaha isn’t vicious in the way it delivers its impressive load of horsepower, you can all too easily get lulled into a false sense of security—until you inevitably hold the throttle open a fraction of a second too long and then realize that you're going much faster into a turn than you had thought. At such moments of truth, there’s no need to panic; just place your trust in the Yamaha’s superb chassis, and— with a little luck and a modicum of skill—it’ll get you out of trouble.

Obviously, Yamaha has done a superb job of harnessing all that power. The OW behaves in a totally neutral fashion whether braking or accelerating; no squiggles or squirms, no twists or turns. Under hard acceleration, there is a noticeable squatting of the Ohlins rear shock, whose revised rising-rate linkage is the only change on this year’s chassis.>

The only aspect of the mechanical package I didn’t really care for was the gearchange mechanism, which felt rather notchy and mechanical, regardless of whether or not I used the clutch while shifting. The shift from first to second, used once a lap at Misano, was especially harsh, and a couple of times it took three stabs at the lever before finding second.

I found the stiff shifting particularly odd, seeing as how the OW’s compressed powerband made gearchanging more critical in 1986. That narrower power spread also rendered the mating of gear ratios to any given track more critical. As Yamaha’s ace tuner, Kel Carruthers, explained it, “We have a total of 32 different ratios, which in theory gives us practically unlimited choice of how to set a gearbox up. But surprisingly enough, there still sometimes are not enough choices.” When a swap is called for, changing internal ratios is quick and easy enough, for the cluster slides out from the right side of the cases. There’s a choice of seven possible ratios for bottom gear, six for second, five each for third and fourth, four for fifth and five for top.

However many possible permutations that allows, the combination of ratios Eddie Lawson had selected for Misano, along with the Yamaha’s smooth, strong, but still ultra-flexible power, enabled me to cut down on gearchanging. I could use the engine’s excellent torque to zap down short straights with only a single shift, whereas on other bikes, such as the Honda Triples or the Suzuki Fours, two would have been necessary. The power-valve system apparently does its job well; and together with all the other factors, it makes for a bike that, for all its impressive power output, is surprisingly easy to ride—well, easy until you have to really ride it to beat the likes of Wayne Gardner, that is. Then I’m sure it becomes real difficult.

An illustration of the difference between riding a bike like the OW81 at maybe 80 percent of its potential as I was doing, and 101 percent as Lawson and Rob McElnea do, was provided by the brakes. For me, the Brembo discs and calipers worked extremely well, providing that reassurance one vitally needs to haul down so fearsomely fast a bike for the turns. But the Brembo calipers weren't good enough for Messrs. Lawson and McElnea, and the previous day, both had been racing with AP-Lockheed calipers fitted—for political reasons, no doubt, removed for my test session.

Unlike other current 500cc GP racebikes, the Yamaha doesn't use any form of anti-dive on the 41mm front fork, which is made to Yamaha’s specs by KYB. Yamaha instead relies on dual-rate springing to prevent the nose of the bike from dipping unduly under heavy braking, while retaining an acceptable degree of suspension movement. But I have to admit that while I did some pretty forceful braking at Misano, I never was able to brake hard enough to get the front suspension to freeze—and the track surface there is now rough enough after a couple of truck races to really test a bike’s handling.

I also noticed that the Yamaha required a good bit of effort to be banked into corners, which was the only real handling fault I could discover. The head angle is a fairly conservative 24.5 degrees, which, together with the 17-inch Michelin radiais fitted front and rear, may partly explain things. And at 55inches, the wheelbase is a little longer than some of the competition’s, which could explain the decided understeer I felt on the bike. It isn’t so noticeable that it becomes a serious detriment, but the bike does require a good tug to be laid into a turn. Once you've got it heeled over, though, the bike stays absolutely on-line and doesn't deflect, even over some fairly horrendous bumps.

But heavy steering or not, what we have here is a magnificent motorcycle, one which has been honed to a fine pitch of competitiveness and reliability. For sure, Honda will have to work hard over the winter to match or surpass the achievement that the OW81/B Yamaha represents in its present state of development. But then, at this time last year, that’s exactly what we said Yamaha would have to do to catch up with the Honda NSR500.

Look what happened after that.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialSeoul-Searching

February 1987 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1987 -

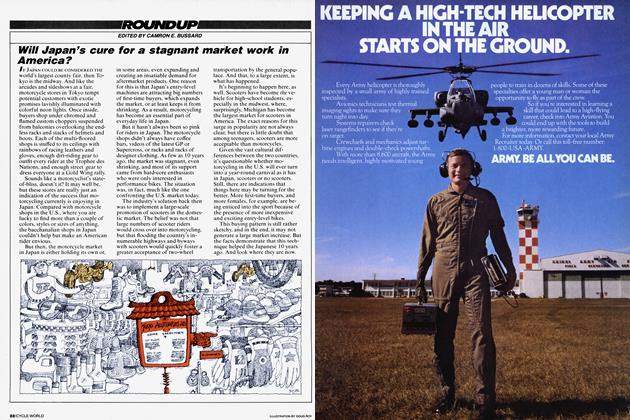

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Summary

February 1987 -

Roundup

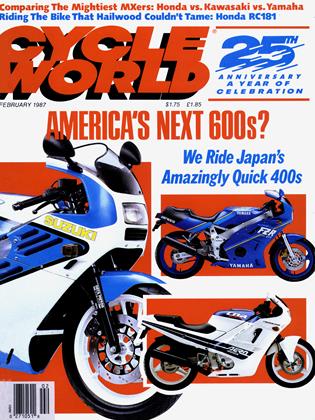

RoundupWill Japan's Cure For A Stagnant Market Work In America?

February 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupWhen School Is Meant To Be A Drag

February 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupHonda's Entry-Level Sportbike: Destined For America?

February 1987 By Koichi Hirose