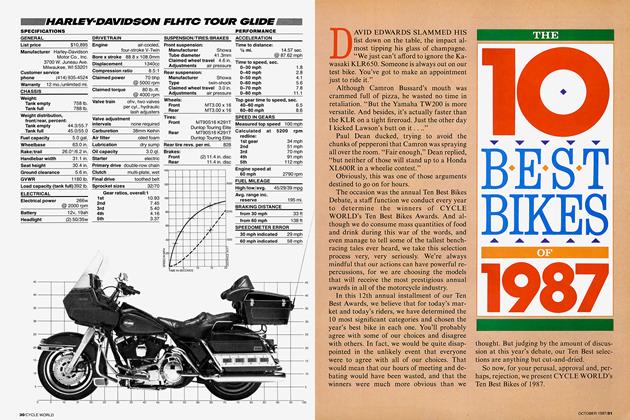

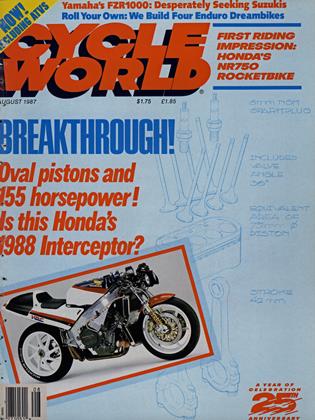

INSIDE THE NR

Oval-piston mathematics: when 4 equals 8

LE MANS, 1979:

HONDA’S MUCH HERALDED RETURN TO Grand Prix racing is not going well at all. Both of Honda’s NR500s, complex and exotic four-strokes designed around unique oval pistons, are suffering enough teething problems to keep their mechanics busy for the next year, and neither has qualified for today’s French GP. Takeo Fukui, the engineer charged with the NR500 project, decides to send them to pregrid anyway, hoping that they may make the race in a reserve position if qualified machines fail to show. The French race officials think otherwise; in a confrontation on the start line, the officials have both NRs physically removed from the grid. The embarrassment of the Honda team is keen, and is further increased when the European press nicknames the NR the “Not Ready 500.”

LE MANS, APRIL 1987:

TAKEO FUKUI, NOW THE DIRECTOR OF Honda Racing Corporation, has returned to this French racing circuit, but this trip feels nothing like his first. Yesterday, Honda’s latest RVF750 endurance racer, derived from the V-Four Interceptor and incorporating many of the lessons learned in the course of NR500 development, won the fabled Le Mans 24-hour endurance race. Yet another victory added to the long list of endurance, Superbike and TT1 successes scored by V-Four Hondas over the past five years. But even more satisfying for Fukui was the public debut of the NR500’s son and heir, the new NR750 endurance racer. It qualified on the grid only a fraction of a second behind the lead RVF, and displayed scintillating speed before retiring after three hours with what was announced as a loose rod bolt—an assembly error rather than a design faux pas with an engine that had already done 24-hour tests at racing speeds with no component failure.

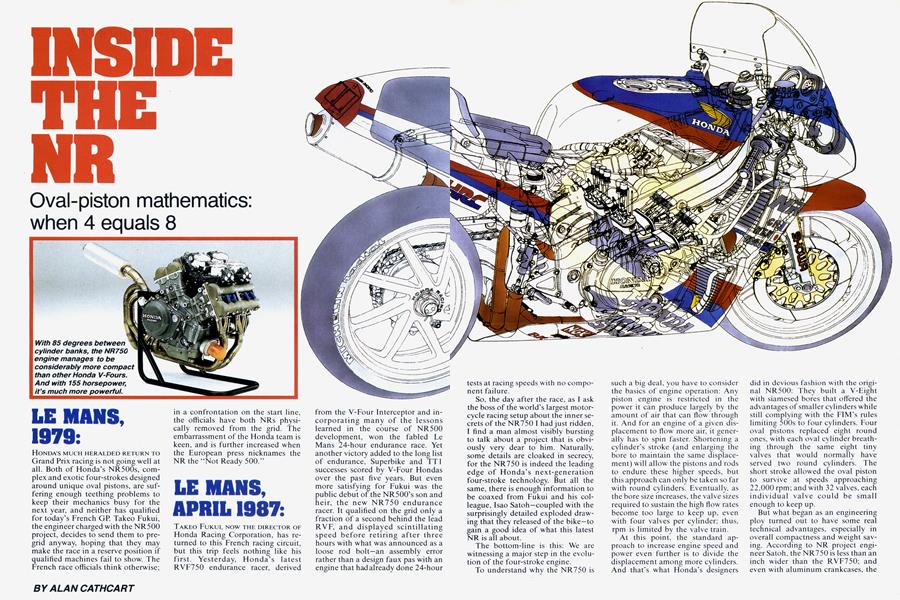

ALAN CATHCART

So, the day after the race, as I ask the boss of the world’s largest motorcycle racing setup about the inner secrets of the NR750 I had just ridden, I find a man almost visibly bursting to talk about a project that is obviously very dear to him. Naturally, some details are cloaked in secrecy, for the NR750 is indeed the leading edge of Honda’s next-generation four-stroke technology. But all the same, there is enough information to be coaxed from Fukui and his colleague, Isao Satoh—coupled with the surprisingly detailed exploded drawing that they released of the bike—to gain a good idea of what this latest NR is all about.

The bottom-line is this: We are witnessing a major step in the evolution of the four-stroke engine.

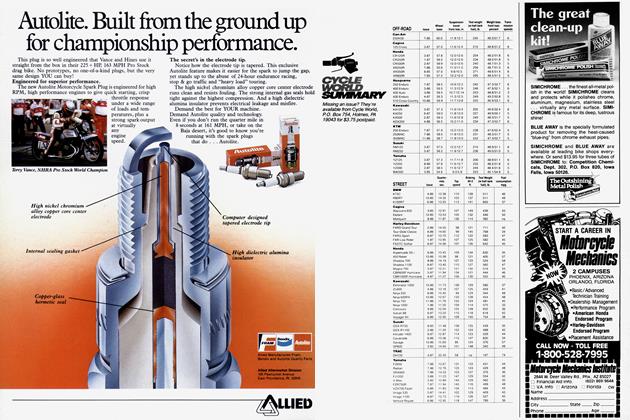

To understand why the NR750 is such a big deal, you have to consider the basics of engine operation: Any piston engine is restricted in the power it can produce largely by the amount of air that can flow through it. And for an engine of a given displacement to flow more air, it generally has to spin faster. Shortening a cylinder’s stroke (and enlarging the bore to maintain the same displacement) will allow the pistons and rods to endure these higher speeds, but this approach can only be taken so far with round cylinders. Eventually, as the bore size increases, the valve sizes required to sustain the high flow rates become too large to keep up. even with four valves per cylinder; thus, rpm is limited by the valve train.

At this point, the standard approach to increase engine speed and power even further is to divide the displacement among more cylinders. And that’s what Honda’s designers did in devious fashion with the original NR500: They built a V-Eight with siamesed bores that offered the advantages of smaller cylinders while still complying with the FIM’s rules limiting 500s to four cylinders. Four oval pistons replaced eight round ones, with each oval cylinder breathing through the same eight tiny valves that would normally have served two round cylinders. The short stroke allowed the oval piston to survive at speeds approaching 22,000 rpm; and with 32 valves, each individual valve could be small enough to keep up.

But what began as an engineering ploy turned out to have some real technical advantages, especially in overall compactness and weight saving. According to NR project engineer Satoh, the NR750 is less than an inch wider than the RVF750; and even with aluminum crankcases, the oval-piston engine is just 6.5 pounds heavier than the RVF unit. All the more remarkable when you consider the V-Four RVF’s 70mm-by48.6mm bore and stroke, compared to the NR’s piston-area equivalent of a 75mm bore combined with a 42mm stroke. Or compare the RVF’s 132 horsepower with the NR’s 155. Of course, that’s if you think of the NR750 as a V-Four; but as Fukui readily admits, it’s really a V-Eight.

“Without the artificial restrictions imposed on engine development by the Grand Prix regulations,” says Fukui, “we would have achieved more horsepower and engine efficiency, if necessary, by increasing the number of cylinders. By comparison with a Four, a six-cylinder engine would only give us a small increase in performance yet would be bulkier. Only a V-Eight can give the improvement we want, but even it would be too bulky unless we use the oval-piston design we developed first with the NR500. In this way, we can build a V-Eight which is as compact as a VFour, yet offers much greater engine performance.”

Students of Honda racing lore will recall the company’s largely successful efforts to fend off the two-stroke challenge from Yamaha and Suzuki in the 1960s by following the same trend to smaller cylinders, more of them, and higher revs, yielding ever higher power. The NR750 sits firmly in this Honda tradition; More is better.

The NR500’s first, abortive race took place at Silverstone in 1979. By the time its final racing version appeared in 1982 it had changed greatly, supporting Honda’s contention that all along it had been a rolling testbed for the company’s newgeneration four-stroke technology.

Has the NR750 evolved directly from the GP bike? “We stopped NR500 racing activity at the end of 1982,” Fukui replies, “but then in 1983 and '84 we developed the 250cc turbo GP engine—only on the dyno, though; never in a chassis. This, too. used an oval-piston design. But in 1 984. planning started for the NR750, with the first engine built in 1985. Now we are concentrating on this, though we may perhaps return to the turbo engine sometime in the future.”

Did the development of the turbo have a bearing on the NR750? “Yes,” says Fukui, “it taught us many little things which on their own are not so important but together give valuable experience. The turbo’s combustion chamber, for example, is quite different than the NR750’s, but in designing it we learned many lessons which were later applied to the NR. Then there.were other things like valve and piston-ring design, which had a direct benefit on NR750 development. Many people think the turbo project is abortive, but at HRC we learn all the time many new things.”

How different is the NR750 inside from the NR500? “The main difference is the crankshaft: The 500 had needle-roller big-ends, because for sprint-type GPs, crankshaft life is not a problem. But on the NR750, we use plain bearings on the big and small ends, with a similar metal specification to the RVF. Correct design of the oil system is important, but the oil is the same as we use in the RVF— SAE 30 synthetic.”

Still, with maximum race revs of 1 5,000 rpm. that’s quite a feat. Why did HRC choose endurance racing to develop the oval-piston concept? “One reason,” Fukui states, “is that we wanted to evaluate the eight-valve NR directly against the four-valve RVF, which gives us a known performance against which we can judge the effectiveness of our new design. Racing a new NR500 against twostrokes in the GP class would not give us this opportunity, because you must compare four-stroke to fourstroke to get effective data. Also, at this stage the most important thing for us is to test reliability and durability under race conditions, factors which 24-hour endurance racing gives us a unique opportunity to explore. Finally, there are just a few major races which permit the use of fourstroke prototype engines, and I think this is a very great pity. Probably, for this reason, our next race with the NR750 will only be here at Paul Ricard in September in the Bol d'Or if it, too, has a prototype class like Le Mans.”

Fukui declines to reveal the valve sizes, but says they're not so different from the NR500’s and employ Honda’s usual 10-percent differential between inlet and exhaust. Did they ever try a six-valve head, as rumored on the turbo? “No, never. The four-valve cylinder-head system is very good, and since what we have here is a V-Eight with paired cylinders, we doubled the number of valves to eight. Our design is very similar to a conventional four-valve. On conventional, circular cylinders we do not believe that more than four valves is efficient, because more than this number leads to compromises in piston and combustion-chamber design.”

How about a single connecting rod per cylinder, instead of the two per oval piston currently employed? “We did make tests with a single con-rod design,” admits Fukui, “but the result was heavier than using twin rods, since we had to use steel to gain sufficient strength. By using two rods, we can make them smaller and use titanium, which gives less overall reciprocating weight.”

The first NR500 had a 100-degree angle between the two banks of cylinders, later narrowed to 90 degrees on subsequent versions, just as on the street-going Interceptor motors. The NR750 is narrower still, at 85 degrees, to achieve an even more-compact power unit, although that angle does cause slightly more engine vibration. And judging by the shrill exhaust note and the line drawing supplied, the crankshaft is a 360-degree unit. The crank looks to be a more nearly conventional affair than the NR500’s, which was almost completely lacking in flywheels, improving acceleration at the expense of riding ease. On the NR750 there are slim but definite flywheels to give some degree of inertia and make smooth operation easier.

Of course, the heart of the matter is the oval piston design, which has been the subject of much experimentation. “We tried two-ring pistons in testing,” states Satoh, “but encountered sealing problems. Three rings are better for oil consumption, but the most difficult factor is the seal of the rings at the point where the piston stops curving and becomes straight. We tried many types of rings before the design we use now, and still we are not satisfied.”

One can only speculate on the design of the combustion chamber on the NR750, with the twin, specially made 8mm NGK plugs per cylinder, centrally located between each quartet of valves. Valve angle is a fashionably flat 18 degrees from the vertical, for an included angle of 36 degrees. This is an interesting progression from the first version of the NR500, which had its valves pitched 65 degrees apart. Each of three following generations of 500 had different and increasingly tighter valve angles, with the final engine having its poppets angled 37 degrees apart. So the 750 is continuing Honda’s move toward more-compact and quickerburning combustion chambers. Opening the valves are bucket-type cam followers, pushed by cams that are gear-driven directly off the right end of the crank.

The chassis in which this avantgarde powerplant has been placed is a beefed-up clone of the RVF’s excellent twin-spar aluminum frame, but with (according to Fukui) fewer compromises because of the greater concentration of masses in the engine design. Wheelbase is the same as the VFour’s at 54.7 inches, but the bike is slightly less front-heavy at 51 percent front/49 percent rear, with fuel but no rider. The four pairs of twinthroat Keihin carbs, presumably smoothbores of undisclosed throat diameter, nestle between the Vee of the cylinders. It’s rather surprising that fuel injection wasn't fitted to this radical engine. The six-speed transmission has a version of the oneway sprag clutch fitted to the RVF’s V-Four, and ignition is by CDI. Cycle parts are otherwise very similar to the RVF's.

With a dry weight (with oil) of 348 pounds in endurance trim, complete with lights, generator and electric starter, the NR750 is already lighter than the RVF, yet produces 20 percent more power and is effectively no wider or longer. Without the endurance kit and the extra crash protectors deemed necessary, HRC surely could crack the 330-pound mark easily with the bike, yet still utilize alloy cases such as might be fitted to production bikes. Sounds like a pretty potent contender for the inaugural World Superbike title in 1988—and a devastating street machine if rumors that abound of a production NR750 to be launched at the Tokyo Show this autumn prove right.

Fukui refuses to be drawn on this topic: “At this moment we have no plans for road versions of the ovalpiston design,” he asserts, “but HRC is working on many types of new technology—not just eight-valve designs—which Honda Motor Company will decide whether to use in production or not.” In other words, it’s not his decision. But there’s no doubt that the adoption of the NR concept is in the cards for future generations of Honda street machines.

The only question is when.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialSummer of '47

August 1987 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1987 -

Departments

DepartmentsSummary

August 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Ysr50 Phenomenon

August 1987 By Ron Griewe -

Roundup

RoundupBeyond the Performance of the 400s And Into the Price of the 750s

August 1987 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupVelocettes Live Again

August 1987