Greetings from Australia

LETTER FROM Europe

Australia is the prime candidate for the title of God’s Own Motorcycling Kingdom. I discovered this on a recent trip there, and I also found out that the people in Australia, like the people in Europe and other parts of the world, don’t always appreciate their good fortune. It turns out that their land is more than just the home of Paul Hogan, kangaroos, KOala bears, Foster’s beer and a religion called cricket.

Australia offers a nearly ideal motorcycling environment, from a warm climate and uncluttered roads to an out-of-town speed limit of 110 kph (68 mph). With just 13 million people scattered over a territory the size of the U.S., there's lots of wideopen spaces for the dedicated or even occasional dirt rider to explore; and the low population density means plenty of open roads for the street rider to roam.

Post-World War II gasoline rationing lasted longer Down Under than almost anywhere else, beginning a motorcycling heritage on the

part of the general populace. Such was reflected in the large number of Aussie riders and their Kiwi neigh-

bors from New Zealand who trekked to Europe in the Fifties and Sixties to seek fame and fortune in roadracing. That heritage continues today, with Aussies Wayne Gardner and Paul Lewis contesting the ’86 GP season on factory Honda and Suzuki machines, respectively. Gardner is set to become Australia’s first 500cc world champion—though maybe not until teammate Freddie Spencer retires. In the U.S., Australian Jeff Leisk is contesting the Supercross series on a Honda. Australia’s equivalent of Daytona’s Cycle Week is the annual Bathurst race meeting over the Easter weekend, often overshadowed lately by bruising confrontations between the police and bike gangs who gather alongside race fans. But for most Roadracing is not the only form of competition on the continent. Take, for example, John Vevers of Sydney, who is planning an attack on Don Vesco’s world speed record for twowheelers, using a pair of turbocharged FJ 1100 Yamaha engines in his rail. Dyno tests have yielded a reading of 394 bhp at the rear wheel. The attack will likely come either on the Bonneville salt flats or on Australia’s dry beds later this year.

On the highways, however, things aren’t quite as bright as they may seem, according to Chris Beattie, editor of Australian Motorcycle News, the country’s biggest-selling bike paper. “The geography and climate of Australia tend to favor motorcycling,” he told me, “but we have a major problem with the public at large in terms of identity.

We’re in the position America was in 20 years ago before they learned to meet the nicest people on a Honda. People think of motorcycle riders in terms of gangs, bikes and Hell’s Angels. The shoot-up in Sydney last year (when seven people were killed, including innocent bystanders, in an inter-gang shootout)

hasn’t improved matters. Many people still perceive motorcyclists as a threat to society.”

Just as threatening as the image problem is the noise problem. At one point in 1985, a new standard called ADR (Australian Design Rule) was debated in government circles which would have dropped allowable noise levels so drastically that BMW stated it would pull out of the Australian market altogether if the regulation was introduced.

The proposed requirement was so low that no current motorcycle could have met it.

Fortunately, Australian motorcyclists are well-organized as a pressure group and highly vocal in their opposition to governmental legislation, and that has enabled them to fight off most of the politically inspired regulation. But they’re an idiosyncratic lot, as well, which is evidenced by the fact that Australia is Ducati’s second-largest market worldwide (after Japan), and one of Harley-Davidson’s principal export markets. Yet the country’s best-selling motorcycle is the ubiquitous

XL250 Honda, ideal for exploring the wide-open spaces of this huge, empty but friendly country.

In addition, motorcyclists turn out in force for most events; no less than 6000 riders took part in the annual Bill Stalker rally in Melbourne last October, riding in a convoy that took an hour to file past any given point. Organized by the local chapter of the biker’s rights organization MRA, the event even drew nods of appreciation from local police.

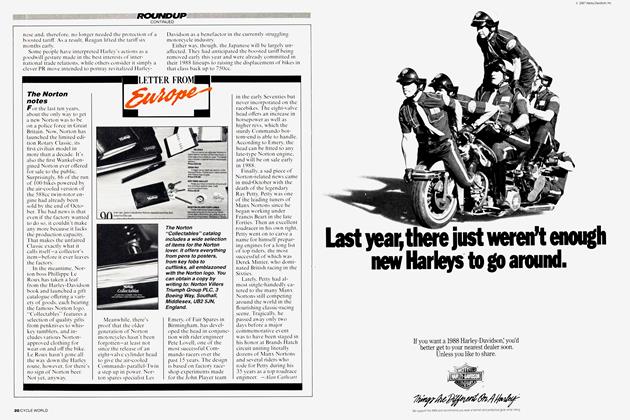

But unquestionably the biggest motorcycle sporting event each year as far as the trade is concerned is the annual Castrol Six-Hour streetbike thrash for box-stock machines. Victory here has a telling effect on new bike sales for the next 12 months, which may explain why Yamaha Australia ran out of RZ500s after winning the race in 1984. A year later they repeated the success at Sydney’s Oran Park Raceway, this time with the FZ750.

spectators it’s a festival of motorcycling, though twice in the past four years the winner of the “Arai

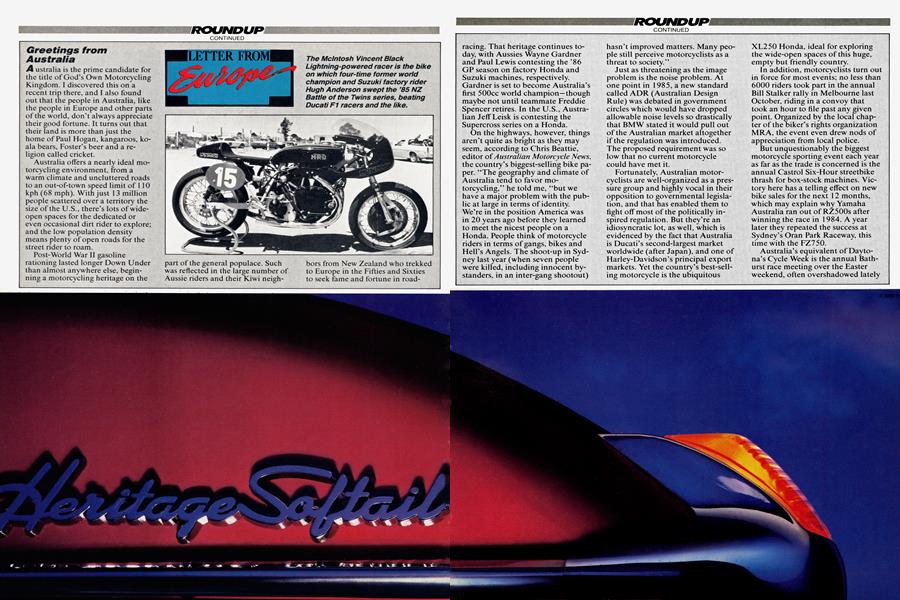

500” main event, a 312-mile marathon over the grueling road circuit, has come from across the Tasman sea: Kiwi Rodger Freeth on his New Zealand-built, 1135cc Mclntosh-Suzuki. Freeth and the bike’s constructor, Ken McIntosh, make an interesting pair. The bespectacled rider is exactly what he looks, a learned academic who had to interrupt his racing season last year to sit (and pass) his Ph.D. in astrophysics, while 24-year old McIntosh is Australia’s only motorcycle manufacturer, having produced over 30 street versions of the Freeth racer, dubbed the McIntosh Bathurst Replica. A new single-shock version, based on the ’85 Arai 500 winner, has just been constructed in McIntosh’s Auckland workshops. First round of the ’86 series was won by McIntosh’s latest creation, though. Dubbed “Lucifer’s Mallet,” it’s an XR1000 Harley-Davidsonpowered racer.

There are other forms of unusual competition, perhaps the most famous of which is the Round Australia Run, which is Australia’s equivalent of the Cannonball Run once held in the U.S. The current record for the 9400-mile trip around the coastline of the island continent is six and a half days. Though the route is now entirely paved, it’s still a tremendous feat of endurance and riding skill. The latest effort to beat the record saw Sydney mechanic Gary van Straton just miss out by six hours at the end of a marathon solo ride after his partner, traffic cop Geoff Lord, dislocated his foot on a thrown truck-tire tread on the first day. Hallucinations caused by lack of sleep were the principal reason for Straton missing the record.

The dirt-bike equivalent is the an-

nual Wynns Safari, a 3300-mile, Paris-to-Dakar-style event through the desert outback of central Australia from Sydney to Darwin. Of the 72 bikes that started last year’s marathon, only 14 made it to the finish, with local rider Steve Chapman scoring an upset victory over BMW factory star Gaston Rahier, by just three minutes, aboard his Honda Australia XR600. Rahier led into the last day, then his BMW’s tires suffered a series of punctures that turned the tables. The September, 1986 race is expected to attract full Japanese factory team attention.

But then, the Australians have talents other than riding. Motorcycle inventors in the Down Under are experts in original thought when it comes to new forms of engines. Ralph Sarich has seen his revolutionary orbital engine patent purchased by General Motors, and now Canberra’s Paul Richter has come up with an opposed-piston twostroke power unit that could soon have motorcycle applications.

Much smaller and lighter than existing engines, the Richter two-

stroke is claimed to be considerably more fuel-efficient. Its unique feature is the conversion of linear motion to rotary motion within a tiny area without the use of gears. Each movement of the piston causes orbital movement of the shaft, which is transmitted as a rotary motion to the output shaft, or chain sprocket. Richter claims the engine can be built using present manufacturing techniques and is ready for final development for production. But, after the rotary/the question is, will any manufacturer be brave enough to attempt to build the design.

In all, motorcycling in Australia is diverse and wild. From roadracing to desert racing, competition is a vital part of the Australian heritage. And there are even signs that the street environment may be changing for the better. After all, when you have 69-year-old Father Lex Dunlop, who uses an FJ 1 100 Yamaha to visit parishioners in Lancefield, your image can only get better. And there’s more: His neighbor in the next parish uses a Gold Wing.

Alan Cathcart

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

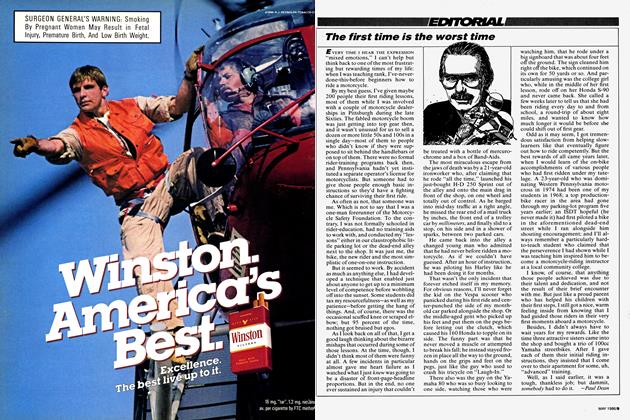

EditorialThe First Time Is the Worst Time

May 1986 By Paul Dean -

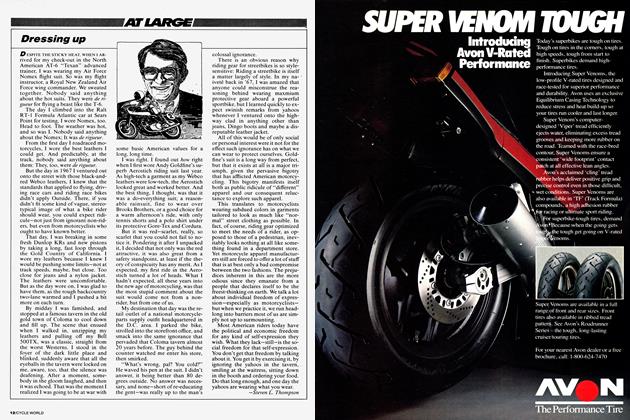

At Large

At LargeDressing Up

May 1986 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1986 -

Roundup

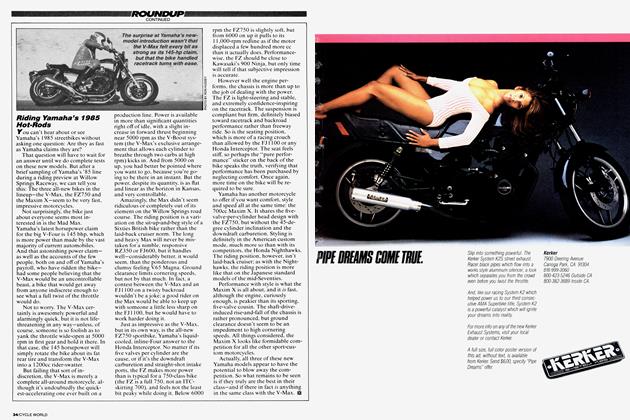

RoundupA Yamaha In Every Living Room

May 1986 -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

May 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

Features

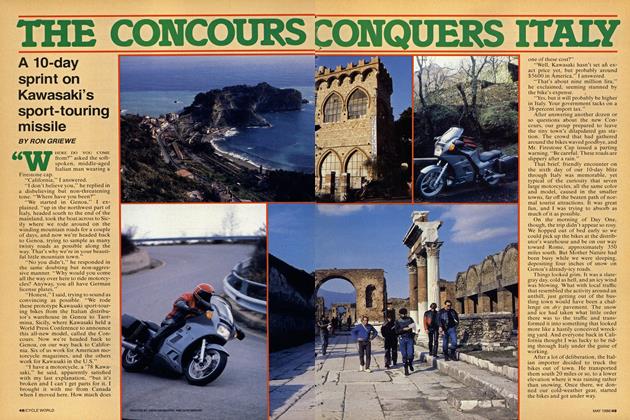

FeaturesThe Concours Conquers Italy

May 1986 By Ron Griewe