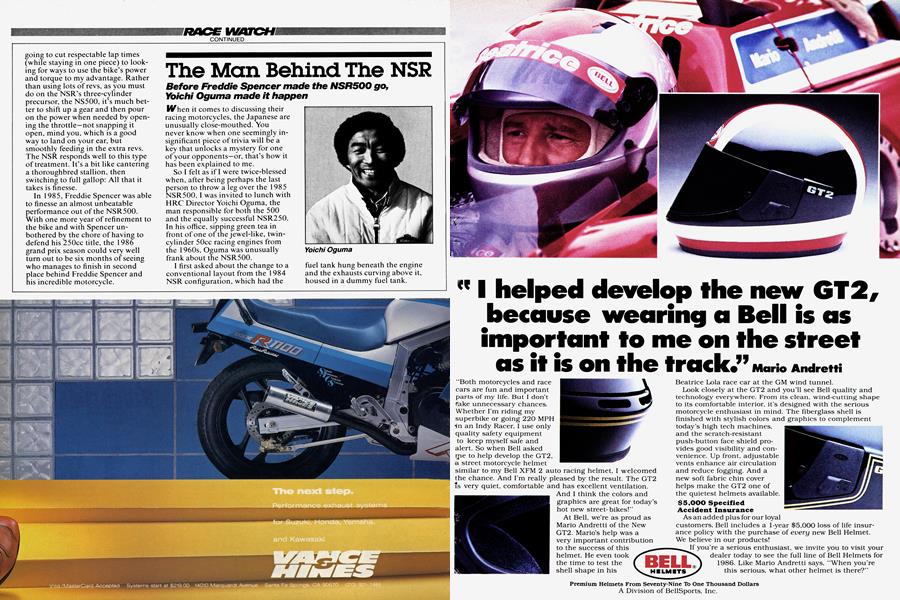

The Man Behind The NSR

RACE WATCH

Before Freddie Spencer made the NSR500 go, Yoichi Oguma made it happen

When it comes to discussing their racing motorcycles, the Japanese are unusually close-mouthed. You never know when one seemingly insignificant piece of trivia will be a key that unlocks a mystery for one of your opponents-or, that's how it has been explained to me.

So I felt a&s if! were twice-blessed when, after being perhaps the last person to throw a leg over the 1985 NSR500, I was invited to lunch with HRC Director Yoichi Oguma, the man responsible for both the 500 and the equally successful NSR25O. In his office, sipping green tea in front of one of the jewel-like, twin cylinder 50cc racing engines from the 1 960s, Oguma was unusually frank about the NSR500.

I first asked about the change to a conventional layout from the 1984 NSR configuration, which had the

fuel tank hung beneath the engine and the exhausts curving above it, housed in a dummy fuel tank. “Maintenance was not easy on the '84 bike,” explained Oguma. “Changing a sparkplug, looking into a combustion chamber, even altering carburetion was a big problem with this machine. Our mechanics had strong complaints about this. Also, a second reason was that cooling performance was not so goodheat dispersal was a problem. Third reason was the rider: Freddie Spencer was not completely happy with the machine’s handling. So for 1985, we changed to the new version.”

Spencer was so unhappy with the original NSR. I added, that there was talk of going back to the VThree that he had used to win the 1 983 championship. Why was that not followed up?

“We could perhaps have produced the same horsepower that we obtained with the NSR by developing the NS500 Triple more, but already this engine had to be revved very high to make strong power, so developing it more would have made the problem worse. We wanted strong power, but also a wide powerband, which the V-Four gives us. Also, the V-Three makes strange vibration, which is absent in the Four. The added vibration of the Three also affects chassis design, quite apart from causing engine reliability problems and sometimes rider fatigue. With a higher vibration level, you must use thicker material in constructing the chassis, which adds more weight. This is one reason the NS500 weighs only slightly less than the NSR, in spite of having a lighter engine.”

And what, I asked, could he tell me about the 143-horsepower. 90degree V-Four, an engine that he had previously called “ideal.”

“It is normally impossible to explain about inside of engine,” said Oguma, “but you come all the way to Japan, so it is a big honor for you to know. The cylinders measure 54mm by 54.5mm. Why so square, you ask? We would have preferred to use an oversquare engine with a shorter stroke, but if we use 56mmby-50.6mm cylinders, for example, the engine becomes too wide. We tried many different combinations, but the results were not so good.” But, I replied, even with the relatively long stroke, the NSR engine revs pretty high.

“Once we chose the bore and stroke, we relied on materials and design to achieve the same results as with the more desirable oversquare engine. In fact, we revved the engine to 1 3.000 rpm on our dyno, but only for test purposes. Freddie says he normally uses 1 1.400 to 1 1,600 rpm, which is better for reliability.

We design the engine to be safe at higher rpm, but Freddie says he doesn't need them.”

One of the reasons that engine width was so important to Oguma was that he had decided to make the new engine a true V-Four, with a single crankshaft, rather than a twincrank engine such as the Yamaha OW8 1. Why go with the inherently wider design, I asked?

“There are many reasons, but the main one is to reduce friction, which wastes power. The Yamaha engine has more frictional losses because it has eight main bearings: The NSR has only five.”

Oguma also dispelled my false belief that Honda had stopped using carbon fiber wheels after Spencer’s disastrous practice crash in South Africa in 1984, when a rear wheel made of the expensive, lightweight material appeared to break up.

“We used carbon fiber wheels on several occasions last year,” he said, “mainly at fast circuits like Salzburg and Silverstone, where there are few slow corners and you keep speeds up. At about 50 percent of the circuits, where there are slow corners, we fitted the alloy wheels, which have a bigger moment of inertia about their circumference because of their extra weight, which assists acceleration.”

Sort of like a pendulum?

“That’s right. But carbon fiber wheels are no problem with Honda now. We use them all the time.” Certainly the carbon fiber helps reduce weight, something that HRC will be trying to do more of on the 1986 NSR500.

Oguma clarified the point: “We say the 1985 NSR is under 265 pounds, but it is really only a little under; so with the 230-pound weight limit for the 500cc class, we must pay great attention to this for ’86. Even getting to 240 pounds will be hard, but we have to try.”

Now that the subject has come around to the new bike, Oguma has reverted, albeit politely, to a more secretive stance. Sensing this, I asked a general question about the 1986 NSR500. Will it be faster than the 1985 edition, already clocked at close to 200 mph.?

Oguma said only one word, but it spoke volumes: “Yes.”

—Alan Cat heart

Trans Americas Rally

How about a motorcycle event that, in terms of distance, makes the famed Paris-Dakar Rally seem like a sprint race? A test of endurance that, by comparison, reduces the ISDE to a mere ride around the block? A competition that begins south of the Tropic of Cancer and finshes, a full month and more than 9000 miles later, north of the Arctic Circle?

Right now, such an event is still in the realm of fantasy. But on August 1 of this year, 99 riders and their trusty motorcycles will gather in Mexico City to set off on just such an adventure. On that date, fantasy starts becoming reality.

This event, tailed the Trans Americas Rally, is a unique concept that will bring together teams representing 33 different countries to compete all across the western region of the North American continent. Each team will consist of three bikes and riders, plus a team manager and a team mechanic. The route will take them from Mexico City, up through the rugged Baja peninsula, into the deserts of the southwestern United States, through landmarks such as Death Valley and the Grand Canyon, high into the Rockies, onto the Bonneville salt flats, up through the Pacific Northwest, into western Canada and Alaska, as far north as Inuvik on the Arctic Ocean, and finally, on August 3 1, into Dawson City in Canada’s Northwest Territories.

Because some parts of this event will take place on public highways, the motorcycles must conform either to EEC (European) or California Highway Patrol standards. This means the use of dual-purpose bikes outfitted similar to those competing in the Paris-Dakar race. The organizers stress, however, that this will indeed be a rally, not a race, and that the course will be laid out so riders can stay on time without exceeding posted speed limits. Riders caught speeding, or who arrive early at the checkpoints, will be penalized accordingly.

Much like in the ISDE, the riders will not be allowed outside assistance while on the course. The team mechanics and managers will be permitted to perform maintenance and repairs on their motorcycles, but only in the impound area, which will be in a different location along the route at the end of each day. Riders will, however, be allowed to help one another on the course: and in an effort to promote goodwill and sportsmanship, bonus points will be awarded to any rider who assists a member of a competing team.

Because the speed averages along the course won’t be high at all, the

winners will undoubtedly be determined not by the arrival times at checkpoints, but instead by the many special tests to be held along the way. The tests will include a one-day observed trials in Colorado, a straight-line speed run on the Bonneville salt flats, a river crossing aboard small rubber rafts, and the descent of a sheer cliff face by bike and rider using ropes.

If that doesn’t sound like your typical off-road event, neither will the criteria for rider participation:

No rider can compete in the Trans Americas Rally who has held an FIM license within the past five years. The organizers want this rally truly to be an amateur event, not one dominated by big-buck factory teams. Also, responsibility for the selection of the riders and mechanics, and for the management of the teams, has been turned over either to the particular country’s national sports council, or to one of its motorcycle publications.

In the U.S., Cycle World has been selected to choose, organize and manage the national team. So here’s your big chance: If you think you’re a qualified rider, one who has all the riding, mechanical, navigational and physical-endurance skills to be competitive in an event of this magnitude, and if you have the credentials to prove it, send us a resumé. Only three riders (and one alternate) will be selected: but if we think you've got the right stuff, you could be in for the adventure of a lifetime. S3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue