INSIDE THE BRITTEN

How to build a motorcycle: First, invent the parts...

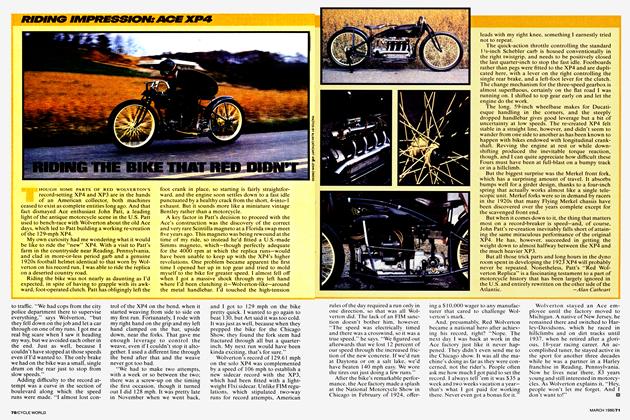

JOHN BRITTEN STARTED WORK ON HIS V-1000 in June, 1988, and it first ran in public not quite six months later. This feat is especially amazing when you consider that he not only designed the whole thing personally, engine included, but made the wooden patterns for the engine castings himself, and laid-up the wet-stressed carbon-rod chassis strand-by-strand.

The engine Britten built is a 60-degree V-Twin with four valves and two overhead camshafts per cylinder. Bore and stroke is 94 x 72mm, for a capacity of 999cc. The 121-pound V-1000 engine is liquid-cooled, and has a wet-sump oil system. To maximize strength and rigidity, the sand-cast aluminum cases are split only at the cylinder-head-to-upper-crankcase joint, and horizontally, along the center line of the crank and gearbox shafts. The finless cylinders are cast integrally with the upper crankcase half.

Cast-iron wet liners are pressed into the cylinders, with coolant circulated by a waterpump adapted from a Suzuki trailbike, driven off the opposite end of the oil-pump shaft by the gear primary drive. Also Suzuki-sourced is the five-speed gearbox from a GS1100, and the clutch from a GSX-R race kit.

The V-1000 employs forged two-ring Mahle slipper piston blanks machined by Britten to match his combustion-chamber design. Titanium conrods from the Cosworth DFX Indycar race engine are fitted. The two rods have split big ends and share a common onepiece plain-bearing crankshaft made by Britten himself, with a single roller main bearing on each side. A screw-on oil filter sits just forward of the clutch on the right side of the engine, with oil feed by external lines to each of the four camshafts.

Those cams are driven by a single toothed belt driven from the left side of the crankshaft, with bucket cam followers and a 30-degree included angle for the four titanium valves per cylinder—37.5mm inlets and 32mm exhausts.

The twin Bosch fuel injectors that feed each cylinder are programmed by a digital control system to deliver fuel only when the valves are open. Programming the system can be done with a laptop-computer. which also can be employed to download the data gathered by the bike’s on-board computer. This memorizes data from the last 10 minutes of engine running, gathered from sensors monitoring air and water temperatures, exhaust oxygen content, throttle opening and rpm.

An additional feature racers of other fuel-injected bikes will be envious of allows the rider to fine-tune the fuel mixture by means of a knob mounted on the dashboard. Thus, the rider is not held captive to the degree of performance handed out by the pre-programmed EPROM chip. Instead, he has the ability to map the fuel flow and injection timing himself, then manually adjust the mixture for optimal performance out on the track.

A test carried out by the German magazine Das Motorrad last year showed that this homemade engine from Down Under delivered 132 horsepower at the rear wheel. More significant, was the fact that the Britten delivered this impressive output at 9500 rpm, yet yielded 100 horsepower as low as 6000 rpm, and again at 10,000 rpm, with maximum usable revs of 10,300 rpm.

Britten's engine needs only to have the front and rear suspension connected to it to form the complete motorcycle. This has been achieved by housing the swingarm pivot in the crankcases, a là Ducati, and by bolting the fork assembly to the top of the engine via a fabricated subframe.

The few chassis parts Britten needed, he built himself. Starting with Kevlar/carbon rods to locate steering head and engine-mounting points, he wet-laid carbon fiber impregnated with uncured resin around and between the rods to create a woven, pre-stressed structure that was then filled with foam and faced off with carbon/Kevlar sheet. This he cured in an oven. Complete with alloy inserts, the resultant structure weighs 9.3 pounds, and the triangulated swingarm, made in the same fashion, weighs 6.6 pounds.

A White Power inverted fork is fitted, but because of the need to keep the rear cylinder’s inlet tract straight, Britten moved the rear WP shock to a vertical position in front of the engine sump, where it’s operated off the swingarm by a long pull-rod and bellcrank offering a degree of rising rate.

Wheelbase is a stubby 55.7 inches, similar to many 500cc GP bikes, while dry weight is 306 pounds.

With race victories ever so close and the possibility of Britten streetbikes in the near future, John Britten's three-year quest to build the world’s best VTwin seems to be paying off. Which just goes to show, if you want something done right, you’ve got to do it yourself.

—Alan Cathcart

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

October 1991 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

October 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

October 1991 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1991 -

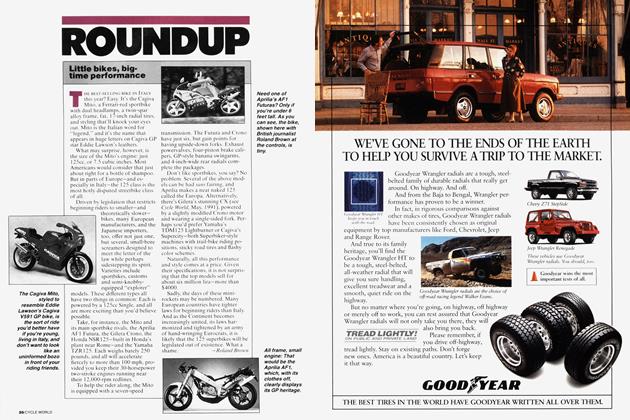

Roundup

RoundupLittle Bikes, Big-Time Performance

October 1991 By Roland Brown -

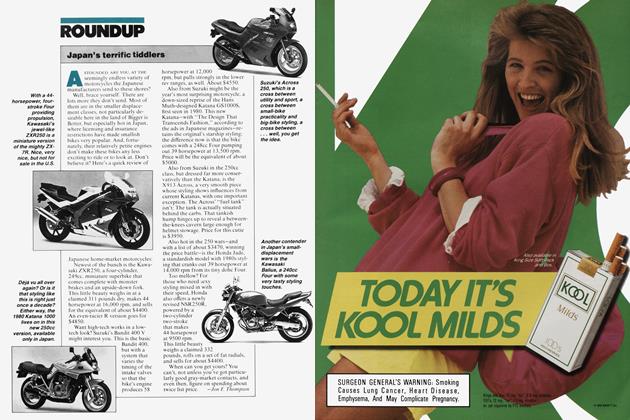

Roundup

RoundupJapan's Terrific Tiddlers

October 1991 By Jon F. Thompson