RIDIN' HIGH

DRILLS, CHILLS, SPILLS AND THRILLS WITH THE VICTOR McLAGLEN MOTOR CORPS

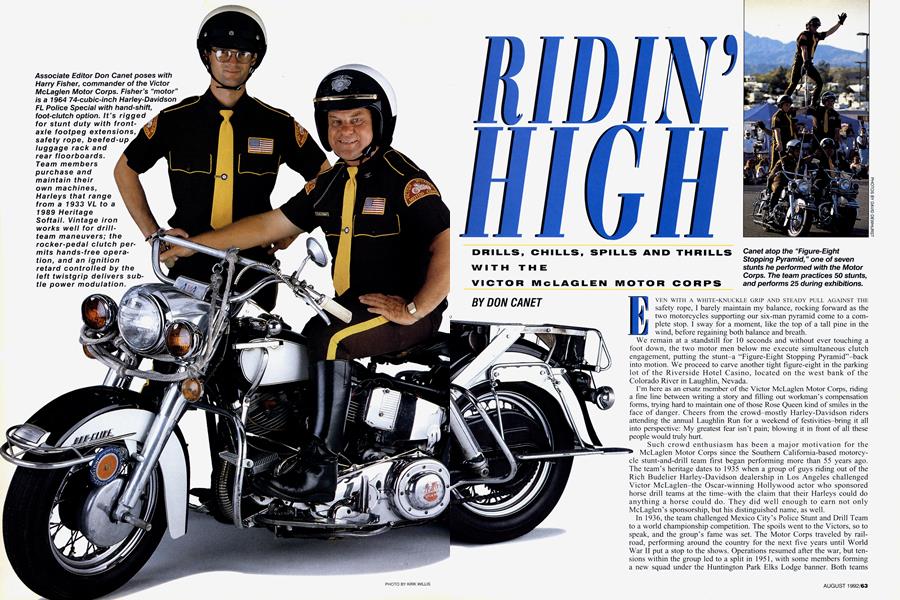

DON CANET

EVEN WITH A WHITE-KNUCKLE GRIP AND STEADY PULL AGAINST THE safety rope, I barely maintain my balance, rocking forward as the two motorcycles supporting our six-man pyramid come to a complete stop. I sway for a moment, like the top of a tall pine in the wind, before regaining both balance and breath.

We remain at a standstill for 10 seconds and without ever touching a foot down, the two motor men below me execute simultaneous clutch engagement, putting the stunt-a “Figure-Eight Stopping Pyramid”-back into motion. We proceed to carve another tight figure-eight in the parking lot of the Riverside Hotel Casino, located on the west bank of the Colorado River in Laughlin, Nevada.

I’m here as an ersatz member of the Victor McLaglen Motor Corps, riding a fine line between writing a story and filling out workman’s compensation forms, trying hard to maintain one of those Rose Queen kind of smiles in the face of danger. Cheers from the crowd-mostly Harley-Davidson riders attending the annual Laughlin Run for a weekend of festivities-bring it all into perspective: My greatest fear isn’t pain; blowing it in front of all these people would truly hurt.

Such crowd enthusiasm has been a major motivation for the McLaglen Motor Corps since the Southern California-based motorcycle stunt-and-drill team first began performing more than 55 years ago. The team’s heritage dates to 1935 when a group of guys riding out of the Rich Budelier Harley-Davidson dealership in Los Angeles challenged Victor McLaglen-the Oscar-winning Hollywood actor who sponsored horse drill teams at the time-with the claim that their Harleys could do anything a horse could do. They did well enough to earn not only McLaglen’s sponsorship, but his distinguished name, as well.

In 1936, the team challenged Mexico City’s Police Stunt and Drill Team to a world championship competition. The spoils went to the Victors, so to speak, and the group’s fame was set. The Motor Corps traveled by railroad, performing around the country for the next five years until World War II put a stop to the shows. Operations resumed after the war, but tensions within the group led to a split in 1951, with some members forming a new squad under the Huntington Park Elks Lodge banner. Both teams coexisted until 1978, when a restructure united the two squads once again.

“Due to insurance and lodge regulations, the Elks were only allowed to perform in California,” says the team’s 46-year-old commander, Harry Fisher-owner of a limousineand funeral-escort service-who took charge of the drill team in 1978, filling the position that Herb Harker had held since 1951. “Now we participate at Elks’ functions, we use the Elks’ facilities, and some of the money we earn goes to Elks’ charities, but we’re the Victor McLaglen Motor Corps.”

I first met up with the Victors last February behind the Huntington Park Elks Lodge, where they were holding their first practice of the 1992 season. Following a 60-day layoff, the guys were getting back into gear by working on the fundamentals. The scene was reminiscent of a ball club in spring training as 15 or so motor men (they don’t call themselves “riders”) wearing matching coveralls and police helmets maneuvered their black-and-white Harley-Davidson motors (never “bikes” or “motorcycles”) through a slalom course of orange cones.

After a quick howdy-do with the team members, I was pushed into my first stunt: the “Horse.” After a bit of instruction and a dry run aboard a stationary bike, it was time for the real thing.

“Build it!” my motor man commanded once we were underway. I carefully stepped from the small platform mounted over the rear fender up onto the shoulders of Harry Fisher, whose 30 years of stunt-and-drill experience boosted my ebbing confidence. I instinctively tightened my grip on the reins, a safety rope that clips on to the handlebar’s crossbar. Then-yee ha!—I was up and ridin’ high as we circled the Elks parking lot. Well, it seemed pretty high at the time.

What followed in rapid-fire order was a succession of stunts with names like the “Shoulder Layback,” the “Swan” and the “Pushup.” By early afternoon, I felt like I’d taken the Devil’s Own Aerobics Class. Then, there I was, positioned 12 feet in the air at the pinnacle of the Motor Corps’ premier stunt, the “4-Motor High/Low Chariot Pyramid.” These guys had me on a learning curve steeper than the sides of their pyramid. I was truly relieved when the day’s session came to a close and I hadn’t broken any bones or lost any teeth. After a couple more Sunday practices, it was time to take the show on the road.

What’s required to be a member of this elite fraternity? “A motor man needs to be a skillful motorcycle rider, have good coordination, balance and a sense for working as a team member,” says Al Ruiz, a 53-year-old machineshop supervisor who started with the Elks team in 1971 and now serves as stunt coordinator for the Victors.

“It requires balance, strength and lots of confidence to be a climber. You have to put your trust in the other members on the stunt,” says Mickey Minor, 59, who came aboard in 1985 following a 23-year Naval career. “Being lighter than most of the members, I wind up going up top much of the time.”

How specialized are the various roles of the performers? “We have several people who can fill any spot on a stunt. It’s important that we remain versatile so that we’re not dependent on any one guy to be at every show.” says Ruiz.

Considering the nature of the team’s activities, combined with a busy schedule-performing at some 30 parades and exhibitions a year-the Victors’ safety record has been very good. Spills are rare and usually happen at walking-pace speeds. “We stress that our people be qualified in doing stunts in practice before using them in a performance on the street. We worry a lot about safety,” says Commander Fisher.

The oldest Motor Corps member is Dick Gerry, 72, and at 30, I wasn’t the youngest. Marty Fisher, the CO’s son, became a team regular three years ago at age 14. “Eve been around it since I was about 4. I would hang around practice and, during a break, my dad would put me on the headlight and do a slow circle,” says the high school senior who recently made the transition from the McLaglen minibike squad onto the full-size motors. “Eve filled in whenever they’ve needed me, riding the headlight or front fender. I went up on shoulders a few times, but fell once and hit my head. Now, I prefer to be a motor man, seat man or safety man.”

One stunt we (thankfully) wouldn’t be repeating during my stint with the team involved piling 21 men onto Harry Fisher’s Harley while he rode in a large circle. “Taking part in the 22man stunt is easily the most terrifying thing that Eve ever done on a motorcycle,” recalls 61-year-old Bruce Chubbuck, the West Coast HarleyDavidson fleet manager who joined the team in 1978 as a liaison officer between the Motor Corps and HarleyDavidson. “The team has never had any official ties with the factory, although Harley has helped finance several trips, including Daytona and Sturgis,” says Chubbuck.

Although the men on the team perform as professionals, nobody is getting rich. “We’re a voluntary organization,” says Fisher. “What money we make performing is used to cover our expenses and our banquet at the end of the season. What’s left over goes to charity.” Listen to Motor Corps members talk about team camaraderie and spectator appreciation, and it’s clear that they love what they do.

“The start of the Hollywood Christmas parade with all the millions of people there is quite impressive, but most of all I enjoy performing in front of our peers-bikers-because these people have a better understanding of what we’re doing,” says 59-year-old Bob Jensen, a welder by trade. Does crowd response have any effect on the 14year team veteran? “During our big finale, the 4-Motor High/Low Chariot Pyramid, I like the sound of the crowd. They’re really cheering, which makes you feel like you’ve done a good job,” Jensen says.

As we went through the program before a crowd of 5000 at Laughlin, I hadn’t figured on stage fright being such a factor. Hell, back in the Elks parking lot, I had my part pretty well wired in the seven stunts I’d be performing in. But here, in front of a live audience, with the intense, non-stop action of one stunt following another, I was stressed to the limit.

But Bob Jensen was right. The crowd’s enthusiasm came to a head during the grand-finale stunt, and my anxiety disappeared as I proudly waved the Cycle World flag from my position on the pyramid. As we rode out of the demonstration area in a twoabreast column, through a gauntlet of smiling, cheering faces, I got a taste of what it is that keeps members of the Victor McLaglen Motor Corps coming back for more. □