UP FRONT

Grand prix plight

David Edwards

THAT MUSHROOM CLOUD YOU SEE RISing on the eastern horizon may signal the destruction of 500cc world championship roadracing.

The Fédération Internationale Motorcycliste, the sport’s governing body, dropped the bomb in July when it announced that come 1993, all 500cc grand prix racebikes will be powered by four-stroke engines running unleaded fuel with no additives. The current, all-conquering two-strokes of Rainey, Schwantz, Doohan, et al will be illegal.

Reaction from the GP race teams and the European motoring press has been swift and surly. “We have no interest in the proposed formula," said several teams. Rothmans Honda ace Michael Doohan w'as quoted in England’s Motor Cycle News as saying. “1 can't believe it. Someone must have swapped their (the El M's) jar of Valium for something else."

Columnist and long-time grand prix watcher Jim Greening suggested that four-stroke GP bikes were “the dumbest idea ever perpetuated by a bunch of incompetents masquerading as authority." British journalist Mat Oxley, writing in American Roadracing, called the new rules “barking mad.” and said, “Bring on the men in the white coats. Ehe FIM seems to have taken leave of their senses; they have finally gone over the top."

1 lave they?

Current 5()()cc racebikes are deplorably expensive, with crankshafts alone that cost more than the average American's yearly take-home pay. The bikes also take inordinate amounts of skill to master. Right now, there are only three or four riders capable of winning races. As a result. 500cc grids have been shrinking, sometimes with as few as 1 3 motorcycles lined up.

The FIM thinks four-stroke racers—if based on middleweight sportbikes—will be easier to build, easier to buy and easier to ride.

1 hat's questionable. As Kenny Roberts, learn Marlboro Yamaha team manager and blatant two-stroke supporter, points out. “You can't just grab a 6()()cc street bike and turn it into a GP bike. It's not that easy." And. given earte-blanche engineering approaches, the factories could easily turn the new four-strokes into hard-to-ride, 20,000-rpm rockets w ith valve trains as expensive as current two-strokes' crankshafts. Grids might not get any larger, and the same few riders would still be at he top of the point standings.

Confused? You’re not alone. Roberts says, “Every time I think I've come to an avenue that makes sense out of this, I hit a brick wall."

Perhaps pulling back a bit, getting the long view, will help.

Current two-stroke GP bikes run on leaded fuel, volatile witches’ brews with octane ratings approaching 120. “Nasty stuff," says one GP observer, who relates the rumor that at least one crew chief has it written into his contract that he doesn't have to come in contact with the fuel. But, after years of unchecked industrial pollution, Europe is in the midst of a rigorous ecology movement, and unleaded fuel, commonplace in the U.S. for years, has recently been introduced. With the changeover in full swing, the FIM’s 1993 rule mandating unleaded fuel is seen as politically correct.

Of course, there are ways of making today's GP bikes run on loweroctane, unleaded fuel. Bimota—with a two-stroke GP Twin in the wings— has put forth just such a proposal, which calls for drastically reduced compression ratios. But another European societal change may sound the death knell for two-strokes.

Tobacco companies now sponsor all the leading GP teams except Cagiva. But the anti-smoking lobby in Europe is strong and getting stronger. Increasingly, countries are severely restricting cigarette advertising, and at several races, teams have to blank-out their sponsors’ logos on bikes, riders' leathers and crew uniforms. By 1993. tobacco companies, either by decree or by choice, may be out of motorsports racing altogether. With cigarette money gone, and little chance of snaring suitably big bucks from other sponsors, more of the monetary burden of fielding grand prix teams will fall on the shoulders of the Japanese manufacturers, all reeling from the effects of an ongoing downturn in the market.

Listen to Rob Muzzy, perhaps the leading four-stroke tuner of our time. “Where the hell did the four-stroke rule come from? I’ve got to believe it came from the manufacturers," he says. “The factories have a hard time justifying the cost (of current twostrokes). There’s no way to write-off anything as development. Right now, the product has nothing to do with what they sell. What you have is brand image, logo awareness. But if you used that money to sponsor a PGA golf tournament, you'd get better exposure for the name.”

With four-strokes. Muzzy says, the factories could better rationalize racing as an R&D expenditure. “They’d have something to sell in a future model; the technology could be marketed," he points out.

So, blame it on the FIM, blame it on the bike makers, blame it on global situations, but the move to four-stroke GP bikes is in motion. There will be more meetings on the subject, more dialogue in the press, maybe even some 1 1 th-hour compromises. But there exists the possibility that the teams and their two-strokes will break from the FIM and start an alternate series.

That could be a disaster. The confusion of two world championships and the constant bickering between the organizations will drive potential sponsors away, and could even cause the Japanese to pull the plug on the whole messy affair and step up involvement in a more stable series like World Superbike.

With the future of the sport’s most prestigious race class in jeopardy, it’s time for the name-calling to stop and the fence-mending to begin. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

October 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

October 1991 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1991 -

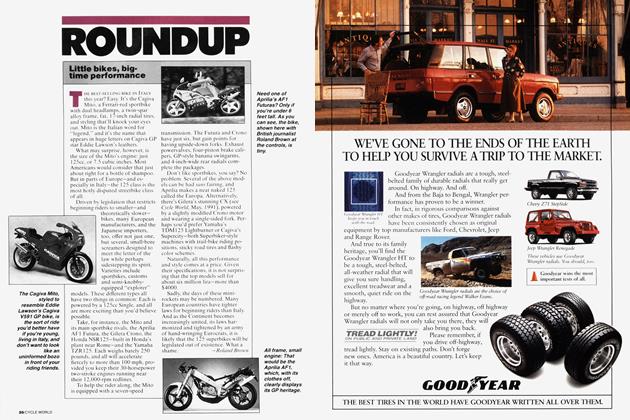

Roundup

RoundupLittle Bikes, Big-Time Performance

October 1991 By Roland Brown -

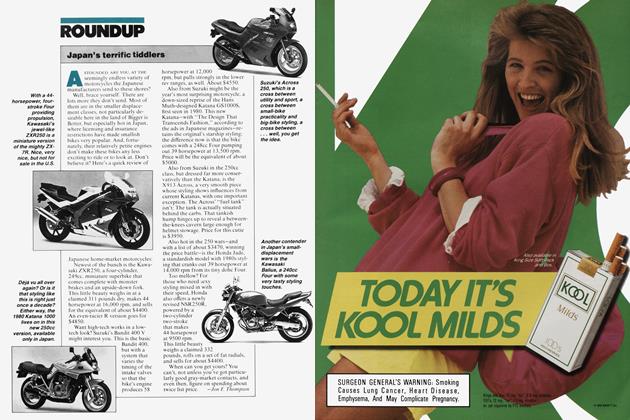

Roundup

RoundupJapan's Terrific Tiddlers

October 1991 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupQuick Ride

October 1991 By Brian Catterson