AT LARGE

Night ride

Steven L. Thompson

SUNSET. CLOUDS EXPLODE IN SURreal colors. The sky darkens slowly. Even in a full-face helmet, a rider feels the intensity of the transformation of the world. When the sliver of sun dips at last below the horizon, when the pink fades from the feathery cloud-edges, when the roadside universe dims from tints to shades and finally to inky blackness, a rider is alone as he never is in daylight.

Sailing along a deserted backroad, with only the stars and the moon for company, the headlight weaving and slicing almost hypnotically through the night, the ride is fine. Finer even than a day ride, in some ways. The senses sharpen, responding to eonsold human engineering that knew the darkness only as a thing to be feared. Eyes open wider, nostrils flare, the skin itself wakes up.

The engine suddenly is easier to hear, to feel. The ears pluck new sounds from the surrounding earth and sky, as if switched on by the coming of night. A rider hears it all: the chain, the tires, the exhaust, the tiny noises lost in daylight. A long night ride nowadays can be a joy ride.

A veteran rider remembers when it was otherwise. When the headlight was a guttering candle, its sickly yellow glow no more use at speed than a prayer. When the jokes about Joseph Lucas were not so funny. When overriding the headlight happened at 45 mph, not 145, and we knew that just beyond the small, faint circle of light on the road lay the hazard we needed to have seen two seconds earlier.

Not so today. Today, technology has tamed the night. Today's halogen bulbs piercing the gloom have changed everything. Or rather, the quiet electric revolution behind them changed everything.

We regard this revolution too little, as we regard many of the marvels of our motorcycles too little. Yet we owe more than most of us realize to the unseen, unsung electrical engineers whose work has transformed our motorcycles and our night rides.

To survive, we must see, and see as perfectly as we can. A rock, a patch of oil. an animal fear-frozen in the road, anything can undo us if we cannot see it. So it has always been bitterly ironic that motorcycle lights were pathetic stepchildren of what could be found on contemporaneous cars. Presented with this paradox, the standard response of the industry was a shrug, underlaid by two realities, one engineering-based, and the other market-driven. The engineer's reality was that the hardware needed to punch big, bright holes in the night did not exist for motorcycles, a situation abetted by the marketing reality, which held that motorcycles had always had lousy lights, and motorcyclists seemed to put up with the state of affairs, so why change it?

As a new generation of motorcyclists discovers yesterday's bikes, and thereby rediscovers the dubious joys of wrestling with quirky magnetos, underthunk and badly built wiring systems, and puny headlights more suited to accenting living rooms than keeping us alive at speed, the contrasts with today’s hardware snaps into focus. The first time you herd an old bike down a country lane at midnight, it's kind of fun. But it takes only one heart-in-the-mouth encounter with an almost-unseen hazard to turn the adventure into something considerably less delectable. Which is a shame, because as its devotees know, night riding is an unparalleled joy, a secret pleasure whose nuances are reserved for those with refined motorcycling tastes.

These tastes are not new; they were familiar 60 years ago to riders like T.E. Lawrence, whose adventures on his Brough Superiors finally ended with his death on one in 1935. Until then, as an RAF contemporary remembered, “It sometimes took place that Shaw (his assumed RAF name) felt like a blind into the night, summer or winter, and would cover as many miles as safety permitted, arriving in camp dog-tired and dirty yet cheery . . . No rider who has become addicted to night rides would need explanation of why."

During a long night ride, when we are fully attuned, it sometimes seems as though the headlight is pulling us along, the interplay of dust or rain or bugs with the cone of white oddlv intoxicating, peculiarly satisfying. As is the reassuring red glow of the taillight on the pavement. We invented electric lights for their f unction, but we derive wholly aesthetic pleasure from the jewel-like purity of their colors at night. Even the turnsignals amuse us.

Asked to define what it is about motorcycling that so enraptures them, many motorcyclists grope fora simple response and finally mutter something with the word “freedom" in it. Nowhere is this kind of' freedom more evident than in riding at night, when the man-made lights of our machines seem to enhance the world made by nature, rather than to distance and wall it offas a car seems to at night. To ride at night is to be, simultaneously, vitally engaged with the problems of perception and performance that accompany darkness, and yet be somehow disembodied.

J

This is an altered motorcycling state. Had we the artists and poets to capture it for us. we might better appreciate the state. Had we the interested scientists, and grants to fund their study, we might know the psychobiology of it. But we have neither. All we have, each day, is another night, and the different world of riding it presents to us.

Night riding is not for everyone. But for those of us fed up with the crowds and noise and jangling of the day, the night world now holds few terrors and many joys. And some of us never forget why. We never stop imagining the one sign that we do not see at night, which ought to be there but is not: IF YOU^C'AN READ THIS, it would remind us in reflectorized letters. THANK YOUR ALTERNATOR. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

October 1991 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

October 1991 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1991 -

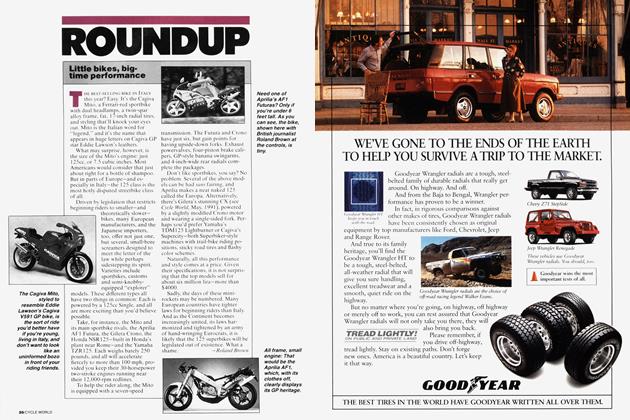

Roundup

RoundupLittle Bikes, Big-Time Performance

October 1991 By Roland Brown -

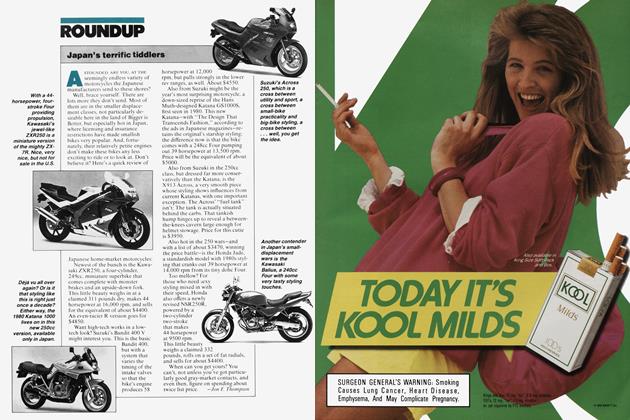

Roundup

RoundupJapan's Terrific Tiddlers

October 1991 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupQuick Ride

October 1991 By Brian Catterson