A Gathering of the Clan

Münch Mammuts meet their maker

JON F. THOMPSON

YOU SAY YOU’VE NO TIME FOR such base examples of motorcycling’s heritage as Gold Stars, Manxes or Broughs? Looking for the rarest of the rare, the most classic of the classic, something you can ride and appreciate while it appreciates? Direct your attention, then, to the strange and wonderful machines of Friedel Münch.

Münch, 63, a smiling gnome with micrometers for fingertips, builds motorcycles. Which is to say he handcrafts them, quite literally, by himself, with the help of his son and two machinists. He started in 1966 and by his count, has managed to roll 472 very individual two-wheeled devices out the door of his Laubach, Germany, shop.

t hey're properly known as Münch Mammuts, the word, translated into English, meaning “mammoth,” a perfectly appropriate description of these tail, powerful brutes.

Got to have one? There is no easy way; certainly no inexpensive way. Used Mammuts occasionally are available in Europe, but at a minimum of about S 1 5,000. And because they're so rare and so ridable, an owner of one of the 3 1 Mammuts in the United States probably will be unwilling to sell without significant financial persuasion. And maybe not even then.

Paul Watts, a Fresno, California, Mammut enthusiast who reckons his 1986, 1800cc, 1 80-horsepower beast is worth maybe $70,000. exclaims, “Sell it? Why? Eventually the money is gone, someone else has your treasure and you don't have the pleasure of its presence.”

It is still possible to obtain your treasure at its source, at Münch’s factory, the end of the Mammut rainbow. All you've got to do is ante up 20 percent of the price—new ma-

chines start at $25,000—sign a contract, and wait from three to five years for Münch to make it for you.

For sure, a long wait. But, says Münch, “I need this time, time to order all the castings, time to handmake everything.”

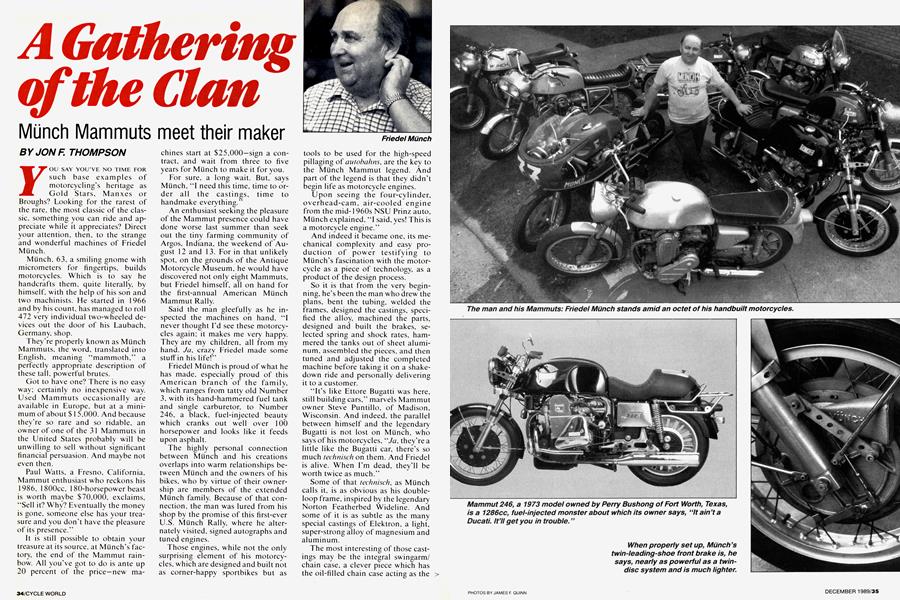

An enthusiast seeking the pleasure of the Mammut presence could have done worse last summer than seek out the tiny farming community of Argos, Indiana, the weekend of August 12 and 13. For in that unlikely spot, on the grounds of the Antique Motorcycle Museum, he would have discovered not only eight Mammuts, but Friedel himself, all on hand for the first-annual American Münch Mammut Rally.

Said the man gleefully as he inspected the machines on hand, “I never thought I'd see these motorcycles again; it makes me very happy. They are my children, all from my hand. Ja. crazy Friedel made some stuff in his life!”

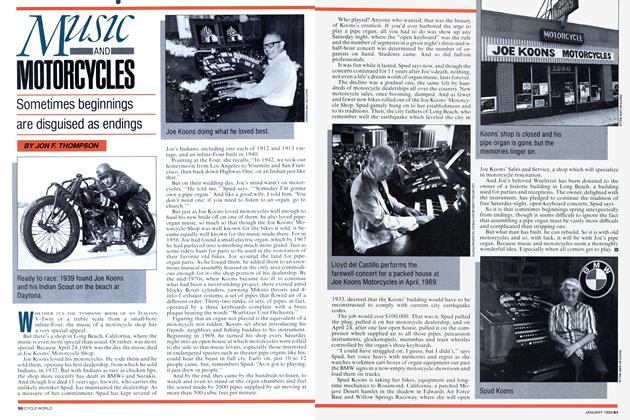

Friedel Münch is proud of what he has made, especially proud of this American branch of the family, which ranges from tatty old Number 3, with its hand-hammered fuel tank and single carburetor, to Number 246, a black, fuel-injected beauty which cranks out well over 100 horsepower and looks like it feeds upon asphalt.

The highly personal connection between Münch and his creations overlaps into warm relationships between Münch and the owners of his bikes, who by virtue of their ownership are members of the extended Münch family. Because of that connection, the man was lured from his shop by the promise of this first-ever U.S. Münch Rally, where he alternately visited, signed autographs and tuned engines.

Those engines, while not the only surprising element of his motorcycles, which are designed and built not as corner-happy sportbikes but as

tools to be used for the high-speed pillaging of autobahns, are the key to the Münch Mammut legend. Ánd part of the legend is that they didn’t begin life as motorcycle engines.

Upon seeing the four-cylinder, overhead-cam, air-cooled engine from the mid-1960s NSU Prinz auto, Münch explained, “I said, yes! This is a motorcycle engine.”

And indeed it became one, its mechanical complexity and easy production of power testifying to Münch’s fascination with the motorcycle as a piece of technology, as a product of the design process.

So it is that from the very beginning, he's been the man who drew the plans, bent the tubing, welded the frames, designed the castings, specified the alloy, machined the parts, designed and built the brakes, selected spring and shock rates, hammered the tanks out of sheet aluminum, assembled the pieces, and then tuned and adjusted the completed machine before taking it on a shakedown ride and personally delivering it to a customer.

“It’s like Ettore Bugatti was here, still building cars,” marvels Mammut owner Steve Puntillo, of Madison, Wisconsin. And indeed, the parallel between himself and the legendary Bugatti is not lost on Münch, who says of his motorcycles, “Ja. they’re a little like the Bugatti car, there’s so much technisch on them. And Friedel is alive. When I'm dead, they’ll be worth twice as much.”

Some of that technisch, as Münch calls it, is as obvious as his doubleloop frame, inspired by the legendary Norton Featherbed Wideline. And some of it is as subtle as the many special castings of Elektron, a light, super-strong alloy of magnesium and aluminum.

The most interesting of those castings may be the integral swingarm/ chain case, a clever piece which has the oil-filled chain case acting as the left fork of the swingarm, an idea Münch adapted because the power of his engines, tuned always for torque instead of maximum horsepower, shredded the chains available to him when he began his work. That kind of old world engineering is applauded by Mammut fans.

“With these bikes you can see the trace of the man’s hand,” muses Watts. “They’re incredibly complex mechanically, yet the design is so attractive—it’s not covered in fiberglass, there’s nothing phony. You can see a human being turned them out.” Added Richard Evans, a Fort Lauderdale, Florida-based owner of two Mammuts, “Maybe 5 to 8 percent of the motorcycle enthusiasts out there have heard of the Münch; most think it’s a handmade creation and say, ‘Oh, isn’t that ugly?’ Well, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. At least it doesn’t look like every other Honda on the road. If you’re at all mechanically inclined, you really appreciate the craftsmanship.”

Craftsmanship or no, it may be a minor miracle that any Mammuts exist, for Münch has proven himself a far better engineer than businessman. The story of the Münch Mammut is, in fact, the story of financial strife, and of backers and business deals gone sour. Münch’s firm, MT Motorentechnik, has survived for the past 23 years in spite of this. Now, he’s on his own.

“I’ve had partners in my life. I didn’t like it,” he says. And he adds, “You need power from yourself to make a motorcycle like this. The problems—everybody has problems. You must make it right. You must (work) until you find the best way.”

These days a good part of that work is not motorcycle-related. His small plant produces hydraulic cylinders for robotic equipment. Says Münch of this work, “The lovely work I do, we make motorcycles. The other work, we make money ... to spend on motorcycles. I am crazy!”

Maybe. But if so, it’s a contagious craziness that causes people to desire his bikes no matter the cost.

“Very rich people call me from Japan. They say, ‘Friedel, make me 15 motorcycles as soon as possible, as powerful as possible.’ They don’t even ask the price,” he says, shaking his head in wonderment.

Though Münch is traditionalist enough to consider the BMW BoxerTwin the only real BMW, traditionalist enough to have changed very little of his own motorcycle’s design over its 23-year life span, change is in the wind. For Münch is a few months away from completion of a secondgeneration Mammut, a machine which will be a significant departure from those built so far, with the only common element being a four-cylinder, single-overhead-cam, crossframe engine.

But this new engine will be liquidcooled, will be fuel-injected, will be served by a supercharger from idle to 4000 rpm and from a turbocharger from 3500 rpm to its 8000-rpm rev limit. And at a time when most other performance-bike designers have deserted the backbone-type frame for perimeter frames, the new Mammut will use a backbone with an adjustable steering-head angle so the owner can, Münch says, dial in the amount of steering quickness he desires.

Gone, too, will be the Mammut’s traditional 4.50x 18 rear and 3.25x 19 front tires; this new Mammut will use modern rubber mounted on ultrawide rims, though Münch insists he'll stick with an 18-inch-diameter wheel because this, he says, is the ideal size for a motorcycle rim.

What will remain will be Münch’s careful, handbuilt approach to his business, the three-to-five-year wait, price tags that guarantee exclusivity, very stout performance and the willingness to build the motorcycle just exactly as the customer would have it. Münch’s ideas about how to craft motorcycles may have evolved, but his dedication to the task, and to his methodology, haven't changed at all.

Thus, it is possible to acquire what may be the most-collectible motorcycle ever. All you’ve got to bring to the table are time and money. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

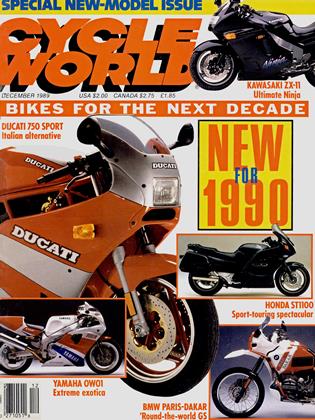

Up Front

Up FrontWelcome Back, Honda

December 1989 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeThe Year of Riding Dangerously

December 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Museum of Prehistoric Helmets

December 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1989 -

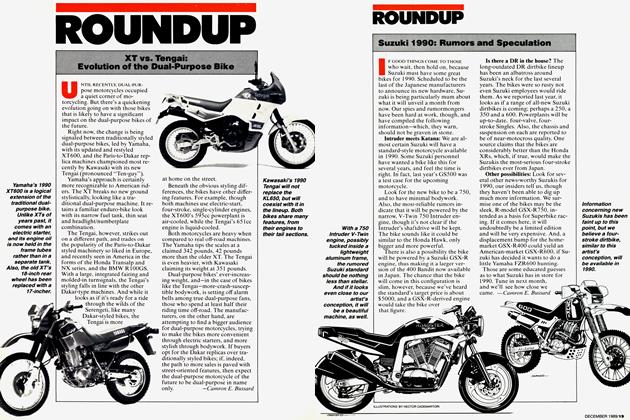

Roundup

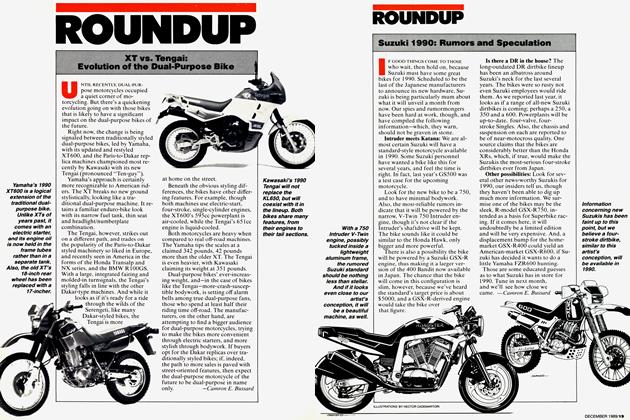

RoundupXt Vs. Tengai: Evolution of the Dual-Purpose Bike

December 1989 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki 1990: Rumors And Speculation

December 1989 By Camron E. Bussard