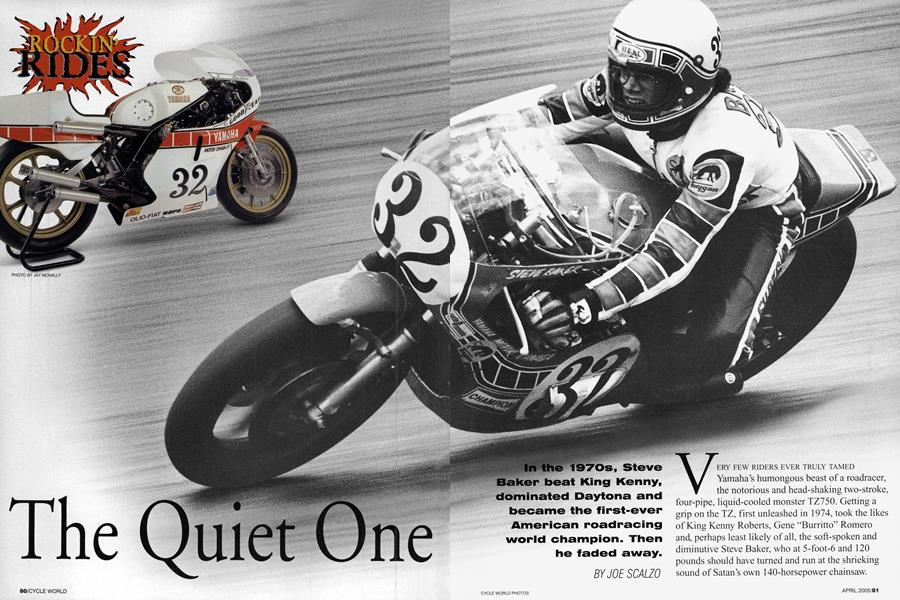

The Quiet One

In the 1970s, Steve Baker beat King Kenny, dominated Daytona and became the first-ever American roadracing world champion. Then he faded away.

JOE SCALZO

VERY FEW RIDERS EVER TRULY TAMED Yamaha’s humongous beast of a roadracer, the notorious and head-shaking two-stroke, four-pipe, liquid-cooled monster TZ750. Getting a grip on the TZ, first unleashed in 1974, took the likes of King Kenny Roberts, Gene “Burritto” Romero and, perhaps least likely of all, the soft-spoken and diminutive Steve Baker, who at 5-foot-6 and 120 pounds should have turned and run at the shrieking sound of Satan’s own 140-horsepower chainsaw.

Through the mid-tolate 1970s, Yamaha constructed and sold 200 TZs, probably more; plus a fair number of improved OW monoshockers. A mystique has sprung up around them, turning these big, bad rockets into cult objects. There’s an owners’ registry, plus a website. The appreciation is well-founded. Even overdue.

Worldwide, plenty of charlatans jacked around with TZs and OWs back in the day, but Roberts,

Romero and Baker remain America’s three great masters. Time has treated them differently. Roberts, dividing his days between the U.S., Spain and England, remains highly visible and hands-on with his own Protonbacked world championship MotoGP squad. Romero operates a popular California flat-tracking series. Stevie, meanwhile, has slipped through a crack and become, “Whatever happened to Steve Baker?” material.

His journey to racing oblivion oddly started at the conclusion of 1977, a summa cum laude season during which he won the Formula 750 world championship on a TZ, not to mention took pole and won the rain-shortened Daytona 200 one day after finishing first in the equally star-studded 250cc tilt. He got into a mysterious cabaret with his employer, Yamaha of Canada. Anticipating praise, perhaps even a raise, instead YoC played Wyatt Earp, drew down, and coolly dispatched its best rider

Baker’s own former Yamahas now being raced brilliantly by Roberts. Offers Baker today, “In retrospect, I don’t know if that Suzuki deal was the best decision.” Back in the U.S. and Canada working his threerace “deal,” Baker was additionally absorbing a hammering from such Grand National newcomers as Roberts prodigy Skip Aksland, Mike Baldwin and Dale Singleton. Then, late in the season, in Canada at Mosport, he and his parttime factory 750 came leaping off a blind hill and-out of carelessness, depression?-Baker struck drift sand, crashed, and

an arm and leg got badly torn up.

“I liked racing, I loved the people and lifestyle,”

Baker says today. “But when I fell off at Mosport, that was enough. My throttle hand was just going in the opposite direction.”

Only 28, suddenly Stevie was all done racing. Returning to his home of Bellingham in rural Washington, just half an hour from the Canadian frontier, he in 1980 opened a SuzukiKawasaki (no Yamaha!) dealership. Hasn’t raced since.

A member of the AMA Hall of Fame since 1999, he is consigned forever to the company of such fellow winner/pariah champions as Carroll Resweber, four-time No. 1, whom Harley-Davidson gave the heave-ho after a debilitating spill; Gary Nixon, two-time No. 1, first demoted and than canned by Triumph; and Rex Beauchamp, Harley heavyweight cut loose by Milwaukee right there in San Jose where he was the two-time mile-track conqueror.

In comparison to Roberts and Romero, who once splashed into a river as occupants of the same skidding rental car, there wasn’t much non-racing buzz to Baker. “I go out and get drunk now and then,” he conceded.

Cool and quiet worked best for him, which was why, after unexpectedly getting Earped, he couldn’t summon the anger to go off on YoC the way he might have been entitled to: Hey, are you people sure you’re letting the right guy go?

The one who beat Roberts and Romero at Daytona, Loudon and Laguna Seca? The guy who beat Giacomo Agostini, Johnny Cecotto, and Katazumi Katayama at Imola? The guy who beat Barry Sheene, Phil Read, Pat Hennen and Gary Nixon in the U.K.’s Race of the Year at Mallory Park? The guy who while getting his very first taste of world championship sport won the 750cc world title, first-ever for an American, and as a secondary accomplishment took runnerup to Bazzer Barry in the 500 GPs?

But, no, YoC was sure. Baker in 1978 scrambled to regroup, wanting to continue racing in Europe for Yamaha, but only given a token deal to do Daytona, Laguna and Mosport. Perhaps the trauma of being backhandedly terminated had done more damage than he’d imagined. He seemed to lose a step. Networked by his Brit pal Sheene, Suzuki’s playboy 500cc world champion, he landed a job in the global tournament on the square-Fours of Suzuki’s Italian distributor, but such indie iron couldn't equal the pedigree of the works jobs of Sheene and Hennen, plus

Baker’s was a lucky career thing got off as to it wasn’t a jump-start, going to which last that of course long. Needing somebody fast to air out its roadracing equipment, Yamaha of Canada glanced south of the border and wisely determined that Baker-then a dirt-track specialist who had only been on a few hooligan runs up and down the Pacific Northwest-could be repackaged into Canadian roadrace champion. He was. Three times.

At burning-fast Talladega-Alabama’s answer to Daytona-Stevie and YoC came parachuting in on the Grand National tour for their initial peeks at Yamaha of America’s dandy duo of then-rookie Roberts and his great bootstrapper and coach Kel Carruthers, the Australian racer/tuner. Adventures on Canada’s short scratch tracks had provided Baker tremendous chops. Whipping Kenny, he took second to winner Kel, all on TZ350s.

That was late 1973, which turned out to be the dying round of a superbly competitive roadracing era. Some magnificent hippodroming had been going on, great fare for the Milwaukee Vibrator XR-750s and lime-juicer Triumph Tridents and BSA Rocket Threes, various light-switch-like Kawasaki and Suzuki strokers, and Yamaha’s very own sweet-dispositioned TZ350 two-stroke.

And then in 1974 Yamaha started a whole new and giddy game, starring its fresh and dominating axe, the 700cc TZ, basically a set of 350s yoked together, double the pleasure, double the fun. The caterwauling thunder of herds of TZs arriving at redline-10,500 revs-became the AMA Grand National Championship’s new franchise sound.

“The 350s before were so manageable,” remembers Baker, “and then they come out with this monster that was so unmanageable.”

Here’s the gig. Back in ’74, TZ engine technology, unfortunately, was years ahead of everything else. So on 140horse road and dirt-track 700s, you also got handlebars that during headshakes went slam-banging against fuel tanks.. .30mm forks-the most heavy-duty Cerriani made-flexing 4 inches...chassis trembling and cracking. . .rear axles bending and motor mounts busting.. .malfunctioning gearboxes with splintering cogs taking the scenic route and blowing bullet holes through crankcases...front ends that grabbed sky and produced, at the tiniest excuse, impossible wheelies...frazzled ignition systems going bananas and searching from cylinder to cylinder before locating and exploding the piston they didn’t like...tortured slick Goodyears, Dunlops and Michelins giving up and pitching handling in the toilet even when tricked-out with wet razor blades. With a TZ you got all that. Carte blanche, baby!

But successes mounted. Among many other scores, Roberts, Romero and Baker all became Daytona winners when the 200 still was glamorous and counted. But the learning curve with a big TZ was crazy-steep, and the difference between spectacular victory and spectacular wreck was slight. Sacrifices mounted, too, not all of them the TZ’s fault. One-time boy wonder Pat Evans bought the farm at Imola; Patrick Pons, a French world champion, did the same at Silverstone; Randy Cleek, jet-lagged and haggard as usual, was typically charging toward another airport when he had a highway smash. Even YoA’s ambitious mile dirttracking experiment ended with its TZs banned and its chassis inventor Doug Schwerma a suicide.

It could was true alter that a man, trafficking and, sure in enough, the taming Baker, of a at TZ the or comOW pletion of 1975, his first full campaign aboard one, had the big beast zap his normally straight hair and twist it into something resembling a pad of Brillo. No, sorry, actually the hair thing had been the work of a crazy haberdasher in Montreal who treated Baker to a radically customized and curled perm. But even today, Baker vividly recalls the haircurling TZ antics.

“The early twin-shock ones, yeah, they scared me,” he says. “I rode the first ones on Canadian racetracks, which were bumpier than U.S. tracks. The suspension was really scary-if you hit almost any bump, it would go into a huge tank-slapper. You couldn’t even hang on to it. I heard Kel Carruthers one time say you should just let go of the bars and it would stop. It worked sometimes, but it would scare the hell out of you in the meantime.”

Rider/tuner teams like Baker and his formidable Canadian wrench Bob Work brainstormed to try to sort things out-not always with good result. Recalibrating his riding technique to accommodate slick rubber, Baker mated a rear slick to a treaded front and dialed himself into a terrible oversteering crash. Later monoshockers were easier to tame, and being both smart and survival-minded, Work and Baker ultimately cracked the handling nut.

The one benchmark everybody cared about was how they measured up against King Kenny Roberts. What made 1976 so hot was that Baker, “after getting beat by Kenny more times than I beat him,” at last felt certain he had the equipment and skill to equal Roberts.

Regarding their two different techniques, Roberts semi-subdued his TZs by moving all over their saddles and distributing bodyweight here, there, everywhere. Racetracks blistered his heavily taped knees, making him roadracing’s most stylistic body-hanger. Baker, by comparison, was more of a “leaner.” Legs too short to do a Roberts, he seldom consented to ripple his kneecaps at all-which, as Roberts himself observed, didn’t prevent Stevie from clocking the quickest TZ cornering velocities.

Both equally matched protagonists suffered through miserable Daytona 200s that 1976, but in the following two nationals at Loudon and Laguna Seca, Baker won resoundingly. Trying to match him at Loudon, Roberts took an uncharacteristic cartwheel.

By the season’s concluding road match at Riverside, all scores were to be settled, the world’s two fastest TZ operators lined up for a handlebar-to-handlebar ballet of 75 glorious miles. Quality time.

It never happened. In a 250cc run-up that Roberts wasn’t even competing in, Baker appeared to be the one major player in an undistinguished field. There was, though, a ringer in the mix, the late David Emde. Youngest member of the dynasty of Daytona winners, David was on the gas of a Yamaha quarter-liter that privateer tuner Mack Kabiyashi had made really fast. Caught unawares by the Emde threat, Baker got sideways in one comer and then, in RIR’s infamous boilerplate-walled Turn 9, miscalculated while squaring things off for a late win-it-or-bin-it shot. Spilling hard, Baker was hospitalized overnight with internal bleeding, dizziness and a stitched-up ankle trashed to the bone. A yawner without him in it, the big national fell easily to Roberts.

Europe’s planetary FIM championship moguls in 1977 to break permitted out, the a full-scale Formula 750 World Series, meat for all of the TZs of the Earth. Baker and Work enthusiastically joined the fray.

Their subsequent campaign may have lacked the pizzazz and spectacle that Roberts and Carruthers delivered the following year in the 500 GPs, but Baker’s 750 world title deserved much more praise than it received.

It wasn’t without its problems. Their first rude awakening on the road to glory concerned continental road circuits, which made Grand National death-traps seem like country clubs by comparison. Notorious Spa-Francorchamps, in mountainous southern Belgium, measured 8 excruciating miles per lap. Despite being edged by looming walls and tough-looking stone villas, the circuit allowed mind-blowing averages of up to 137 mph. During practice, a couple of scooters flipped over embankments; another one boomed upside-down over a bump; several more were pranged.

Come the Grand Prix itself,

Motor Cycle News, the Brit tabloid, reported, “The safety commissioner was taken from the track by police as he tried to redflag riders following a five-machine pile-up in which Hans Stadelman died, and Patrick Fernandez, Dieter Braun and Johnny Cecotto were seriously injured...the race went on with a handful of riders to the catcalls of the 70,000-strong crowd and the clerk of the course was stoned by spectators at the scene of the crash...”

Cecotto, Katayama and the swashbuckling Sheene amounted to Baker’s sternest competition in Europe.

Cecotto was the fiery Venezuelan with a Ferrari who once took Nixon for a screaming Testarossa ride that almost turned Gary’s red locks white. There was some “animosity”

between Yamaha teammates Baker and Cecotto, the latter considered the team’s No. 1 until he was out with injury for part of the season. When they did face off, he and Baker fought to a draw: “Johnny beat me at Paul Ricard. I beat him at Imola,” Stevie recalls.

In smaller engine classes, he had less success going against Katayama, the at-times berserko dingbat whose assault-and-battery reputation was known all across Europe. The Samurai merchant had a taste for hitting things: Katayama clobbered a cottage on the Isle of Man with one TZ, and in Spain on another one unavoidably tore off the leg of a flag marshal. At Silverstone, Katayama and Baker, Yam 250 vs. Yam 250, collided at Becketts Comer with Baker biting the pavement. It was the first time he’d ever encountered anybody who actually was trying to knock him off, but ever the disciple of cool and quiet, Baker afterward let it slide without reproach: “I was pretty peeved off, but he’s a really likable guy.”

Finally there was the rollicking Sheene, the larger-thanlife Londoner who hung with the Beatles, had for a moll the gorgeous Stefanie, and who’d been the third zany party in the rental car that Roberts and Romero made disappear into the drink. He and Baker fought it out for the 500cc GP championship in 1977, with Stevie the close runner-up. Sheene was afterward incredulous about Yamaha terminating Baker, who at minimum was, he said, “as fast as Kenny.”

Lay off your first employee, and you hate yourself; fire your second and you start enjoying it-so goes the Wyatt Earp syndrome, which YoA, late in 1977, was preparing to exploit, too. Not content to allow YoC to have all the fun pink-slipping celebrity employees with wholly substandard offers, YoA decided to get its own jollies by zapping Roberts!

The story is little-known but documented. From its Southern California headquarters, YoA dispatched its majordomo of racing, Ken Clark, on an emergency call to Kenny’s valley fortress in the dry-gulch San Joaquin. Boss Clark’s assignment: try to find out what had happened to all the ’77 budget bucks Kenny had blown visiting 22 dirt-track nationals with nary a win. Responding, Roberts gave up a grocery bag spilling over with $150K worth of receipts, everything from first-class air tickets to lunches at Wendy’s. One suspects he did not display Baker’s quiet diplomacy.

Behaving with more intelligence than its Canadian counterpart, YoA regrouped and decided that giving the heave-ho to its own celebrity employee made no sense, but giving him a second chance might. This in turn led to 1978’s complicated partnership featuring Roberts, YoA, TZ/Kenny-wise tuner Carruthers, Lectron carbs and Goodyear rubber, which turned international roadracing upside-down and led ultimately to three consecutive Roberts world championships. What could Baker have done with a similar opportunity? We’ll never know.

These Bellingham days, 52-year-old homeboy and Baker’s star salesman status is that of Mt. of Baker Motor Sports, the same outlet he opened in 1980 and sold to new owners three years ago. Baker still follows national and international racing, and like everyone else, finds Valentino Rossi “incredible.” (Rossi’s father, Graziano, was a Suzuki teammate during Stevie’s closer season 1978.) Baker no longer sports his Brillo perm, nor does he offer much in the way of regrets or lasting disappointments.

“I missed racing for quite some time after I retired, but that crash at Mosport was a pretty bad one,” he reflects today. “It affected me quite severely. Not only with broken bones, but in my head. I’d lost my confidence, and I thought I’d better sit back and think about that-and not do it from the rider’s seat. I think retiring was the right decision.”

Okay, his Yamaha one last relationship time, so what to does chill? Baker Well, think he just caused doesn’t know, or says he doesn’t. Of one thing he is sure, “I don’t want to slam Yamaha at all.”

Awful generous statement, considering. □

Yamaha ’s customary gathering of champions at Daytona has been moved this year to July ’s USGP at Laguna Seca. Look for Steve Baker and other Yamaha luminaries to be sitting alongside factory racers Valentino Rossi and Colin Edwards. Bring your autograph book.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontProper Choppers

April 2005 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsSustainable Trailer Towing

April 2005 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCApples & Crocodiles

April 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

April 2005 -

Roundup

RoundupRiding the Yamaha Mt-01

April 2005 By Damon I'anson -

Roundup

RoundupDream On

April 2005 By Brian Catterson